The New Tower of Anti-Babel

Featuring: A short history of Prussia, the patron saint of cybernetics, and the Key to Chinese. Part IV of the The Universal Commerce of Light.

“Students of languages and of the structures of languages, the logicians who design computers, the electronic engineers who build and run them – and specially the rare individuals who share all of these talents and insights – are now engaged in erecting a new Tower of Anti-Babel. This new tower is not intended to reach to Heaven. But it is hoped that it will build part of the way back to that mythical situation of simplicity and power when men could communicate freely together, and when this contributed so notably to their effectiveness.”

Warren Weaver, “The New Tower,” (Introduction to “Machine Translation of Languages.” 1955

When Frederick William acceded to the throne of the Electorate of Brandenburg-Prussia in 1640, the region we now think of as “Germany” was a patchwork quilt of states and principalities, some tiny, some larger, some Protestant, some Catholic, all ceaselessly seeking their own advantage while the much larger dynastic superpowers of Bourbon France and the Habsburg Holy Roman Empire battled for continental supremacy.

The Thirty Years War still had eight years to go in 1640. The worst devastation inflicted by this excessively destructive conflict fell on German soil, not least on Brandenburg itself, a fact that did not bode well for Frederick William’s prospects. His father had been an incompetent leader, leaving the 20-year-old Hohenzollern dynasty scion eventually known to history as “The Great Elector” facing daunting challenges: His government bankrupt, his army a joke, his far-flung domains racked by marauding foreign soldiers and plague.

Berlin, the capital of Brandenburg, was no glittering metropolis comparable to Paris or Vienna or Rome. Its population was tiny, its buildings were unremarkable; sadly, it boasted not even a single university. But during Frederick William’s reign, all this began to change, along multiple front-lines. Perhaps most unexpectedly, one of Frederick William’s lesser-known initiatives was the the acquiring of hundreds of Chinese and Manchu manuscripts for inclusion in the Brandenburg court library. It is one of the oddities of history that in only a few short decades this German backwater boasted a collection of Confucian classics rivaled, in Europe, by only Rome and Paris.

As a teenager, Frederick spent a few formative years in the Dutch Republic, then at the zenith of its global influence. The decision to collect Chinese books can be attributed to Frederick’s desire to create a home-grown version of that great pioneering avatar of mercantile globalization, the Dutch East Indies Company. A Brandenburg East India Company tantalized Frederick with dreams of economically fruitful Far Eastern commerce. A prudent and far-seeing man, Frederick decided it would be strategic to gather as much information about China as possible. So he authorized the purchase of Chinese works, and empowered scholars to study them.

The plan to crack the China market for porcelain, silk and tea came to naught. But Frederick’s other major projects, such as the creation of an effective standing army and the stabilization of government finances were more successful, and proved to be crucial steps paving the way for Prussia’s eventual emergence as the pre-eminent German-speaking sovereign state. Frederick William’s son crowned himself King of Prussia; his grandson honed the Prussian army into Europe’s state-of-the art 18th century military force; his great-grandson, Frederick the Great, made Prussia into one of Europe’s Great Powers; and his great-great-great-great-great-grandson Kaiser Wilhelm I, with a little help from Otto von Bismarck, unified all of Germany under Prussian rule.

And then there was Kaiser Wilhelm I’s successor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who plunged Europe into the disaster dubbed World War I, ended the Hohenzollern dynasty, ruined Germany’s economy, and thus can feasibly be accused of laying the groundwork for the rise of Adolph Hitler, who, some historians have argued, took advantage of the special peculiarities of Prussian culture to mastermind the Holocaust.

But that’s probably getting ahead of the story. For now, our attention must turn to a letter written in 1679 by Gottfried Leibniz to a man named Andreas Muller, a specialist in Mideastern languages who had been appointed as provost of a prominent Berlin church by Frederick William, and who was the first “proto-Sinologist” entrusted with building out and exploring the Berlin library’s Chinese collection.

Leibniz’s attention had been previously captured by Muller’s announcement, five years earlier, that he had created a “Key to Chinese,” a “Clavis Sinica,” a kind of instruction kit that he promised would unlock the mysteries involved in learning written Chinese, to anyone, with a minimum of effort.

“[The Clavis Sinica is] a method, in which everyone can read, what is written in Chinese in spite of the well-known fact that [Chinese] deals with an immense number of characters.”

There was one hitch. Muller would only make this “Clavis Sinica” available if paid a hefty sum in advance. And no one, not even Frederick William, his sponsor, was willing to pony up the cash without some upfront proof that it worked. Understandably, Leibniz wanted some details. His letter included 14 specific questions about the Key and the structure of the Chinese writing system.

Among them:

3) Whether the whole language is based on certain common elements, or a basic alphabet from which the other characters are evolved.

5) Whether the Chinese language was artificially constructed, or whether it has grown and changed by usage like other languages.

9) Whether those who constructed this language understood the nature of things and were highly rational.

13) Whether the person having the Key can also write something in Chinese and whether such writing could be understood by a learned Chinese.

Muller refused to answer Leibniz directly. Instead, he shared some comments with another correspondent to the effect that answering Leibniz’s questions would be so time-consuming that “to do so would leave him unable to complete his other work.” He also also complained “that no money had been forthcoming for his Key,” so why should he bother? According to the historian David Mungello, Muller’s response infuriated Leibniz to the point that he starting writing an angry letter to Muller that “resorted to the coarse example that any buyer of a horse wishes first to examine the merchandise.” But he ended up thinking better of such inflammatory rhetoric.

In the end, Muller, after getting embroiled in the kind of deadly serious polemical religious flamewar that was very much the fashion of the times, lost his position as provost and his access to the library, and died without ever releasing his Key, if indeed such a thing ever existed, which is doubtful, because, as has been discussed in these page previously, there is no such thing as a key to the Chinese language. At least not yet. It’s possible we are inching closer.

Leibniz addressed his questions to Muller because he was obsessed with the possibility that written Chinese might offer a model for his “Universal Characteristic” – his plan to create a universal language that could express mathematically provable truths about the universe, solve conflicting questions of faith, and establish peace throughout Europe. His questions all revolved around this grand idea, which, when you hear Leibniz describe it in full, betrays a truly astounding level of ambition.

“Leibniz claimed this invention of Characteristic Numbers was so completely rational that it could serve as a ‘judge of controversies, an interpreter of notions, a scale for probabilities, a compass which will guide us on the ocean of experience, an inventory of things, a catalogue of things, a microscope for minute examination of present things, a telescope for determining remote elements, a general calculus, a simple magic, a non-chimerical Kabbala, a script which each individual will read in his own language.’”

From David Mungello’s “Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology”

When I first grappled with the scope of Leibniz’s imagination, I found it breathtaking to the point of insanity. But further immersion in late 17th century Europe has provided me with more context. Leibniz was hardly alone among his contemporaries in dreaming that a new language – or more popularly, the rediscovery of an old language – could transform the world. The European “savant” community shared a dream: If the original language spoken in common by all humanity before God struck down the Tower of Babel could be rediscovered, then a new era of peace and harmony could begin.

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to another… Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

King James Bible

Tempted as I am to consider at length the extraordinary implications of a divine authority purposely introducing mutual incomprehension into his own creations, thus ensuring millennia of conflict and destruction, all because He was upset at their aspirations to reach heaven, let me just point out here that to Europeans of the late 17th century, such as Frederick William, who came of age at the height of the Thirty Years War, and Gottfried Leibniz, who was born just before its end, the notion of a return to Pre-Babel harmony must have exerted a particularly strong seductive force.

The intensity of warfare throughout 17th century Europe (and for centuries prior) was so ferocious that there is an entire school of thought – the “Military Revolution Model” – that credits the ensuing worldwide colonial primacy of Europe on innovations in science and technology and changes in social structure that were driven by the necessities of armed conflict.

First the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and then most successfully, the English, so the argument goes, parlayed the technological advantages bequeathed by warfare’s Darwinian evolutionary pressure into global conquest.

During this same period China, to be sure, was no utopia of communal bliss, but when you drill down into the details there is simply no comparison between East and West. Europe was a seething battleground for centuries and whoever invented a better bayonet stood to benefit, immediately. White supremacy was a consequence of ravenous bloodthirst driven by religious zeal and territorial greed. It's really not a record to take pride in.

Leibniz hoped to extricate Europe from its concert of repetitive self-disembowelment through unassailable appeals to rationality. Frederick William decided that the only answer to sovereign insecurity was to centralize the power of the state by force of arms. Frederick William’s son connected these dots when he appointed Leibniz as the first president of the newly created Berlin-Brandenberg Society of Scientists. But how this has all ultimately worked out in long run reminds me of Zhou Enlai’s answer to a question from Henry Kissinger asking him to evaluate the success of the French Revolution that we used to think was one of the great put-Western-Civilization-in-its-place smackdowns of all time: “it’s too early to say.”

More to the point: according to David Mungello European interest in recovering a pre-Babelian common ground was stimulated by the European encounter with other cultures precipitated by the first great wave of globalization.

“The seventeenth-century European search for a lingua universalis was the fruit of the cross-fertilization of Biblical tradition, a medieval idea, the sixteenth-century discovery voyages and seventeenth-century science. The European discovery of many new Asian languages conflicted with the traditional European division of languages into sacred and profane, classical and oriental, living and dead. This newfound linguistic complexity revived the Biblical conception of the proliferation of tongues at Babel.”

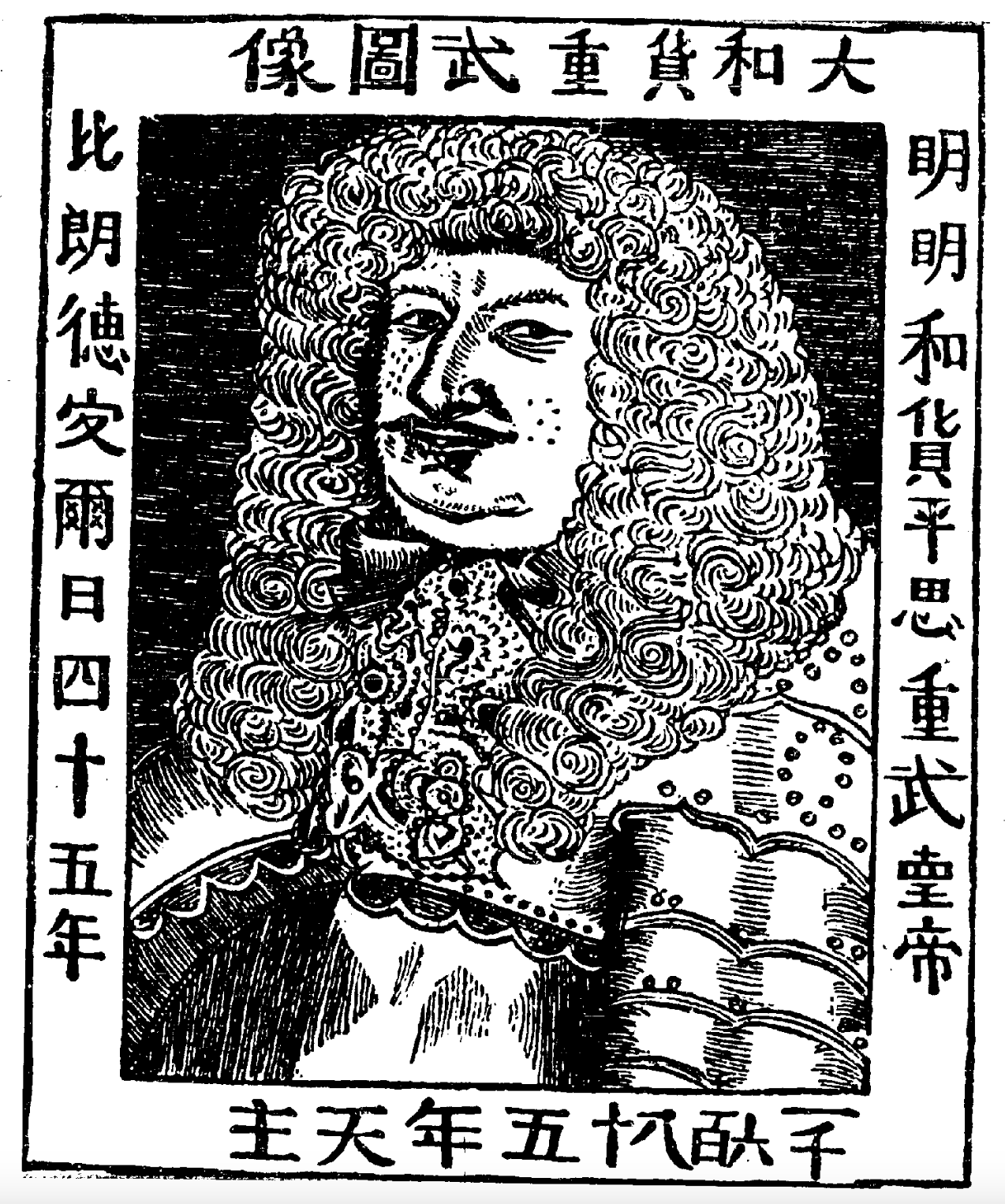

In other words, difference drove enlightenment. Exposure nurtured creativity. Complexity added spice to the broth. And just for a moment, with Jesuits teaching geometry in Kangxi’s court and Leibniz pondering the Confucian classics and Book of Changes at the court of Ernst August in Brunswick, you might have been able to imagine something wonderful emerging from all this hybrid fusion. Something as extraordinary as the artwork I chose to illustrate this newsletter, a portrait of the Great Elector commissioned in 1685 that is surrounded by Chinese characters lauding him as “highly intelligent” and a “warrior.”

But we know how this story ends, and its not with mutual enlightenment but with gunboats and extraterritorial concessions and the sacking of the Summer Palace. Europe did its military revolution model best to crush all that difference under its collective Prussian boot. One has only to think of how the boorish and arrogant behavior of German missionaries operating out of the German concession of Tianjin in the late 19th century was a significant contributing factor inspiring the outrage that resulted in the cataclysmic Boxer Rebellion, to reckon how little of value 17th century curiosity about the deeper meanings of the Chinese language turned out to be.

The curiosities investigated by the savants were always going to lead to dead ends. Because just as there was no such thing as a “Key” to Chinese, so also, unfortunately for our first proponents of “debabelization,” there was in fact no “Primeval Language” that ever united all humanity. We never needed an act of God to make it hard to communicate with each other. Mutual incomprehension is built into our DNA.

But the dream to create problem-solving brand-new languages from scratch never died. And the march of technological progress, whether militarily driven or not, has resulted in technology that some observers believe will finally realize Leibniz’s wildest imagination “in the metal”, as Norbert Wiener declared in Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, first published in 1948.

Centuries after the Jesuits were kicked out of Beijing and Europeans abandoned their Biblically-inspired fantasies, a new generation of language inventors, script reformers, and eventually, computer scientists returned to the same old problem of how we might – how we must! -- improve our ability to communicate with each other. This time around they were not merely motivated by missionary fervor or dreams of utopia, but profoundly incentivized by the all-encompassing competitive pressure generated by capitalist modernity’s mandate to relentlessly seek labor-saving efficiency in every modality of human existence.

But for that part of the story, readers will most likely have to wait until the next chapter.

End of Part IV…

… well almost. I can’t resist including in full this wild passage by Norbert Weiner dubbing Leibniz “the patron saint of cybernetics.”

At this point there enters an element which occurs repeatedly in the history of cybernetics—the influence of mathematical logic. If I were to choose a patron saint for cybernetics out of the history of science, I should have to choose Leibniz. The philosophy of Leibniz centers about two closely related concepts—that of a universal symbolism and that of a calculus of reasoning. From these are descended the mathematical notation and the symbolic logic of the present day. Now, just as the calculus of arithmetic lends itself to a mechanization progressing through the abacus and the desk computing machine to the ultra-rapid computing machines of the present day, so the calculus ratiocinator of Leibniz contains the germs of the machina ratiocinatrix, the reasoning machine. Indeed, Leibniz himself, like his predecessor Pascal, was interested in the construction of computing machines in the metal. It is therefore not in the least surprising that the same intellectual impulse which has led to the development of mathematical logic has at the same time led to the ideal or actual mechanization of processes of thought.