The Universal Commerce of Light

In which Gottfried Leibniz consults the Book of Changes and invents digital technology. With cameos from Neal Stephenson, Philip K. Dick, Joseph Needham, and eventually, The Chinese Computer.

Everyone agrees that the decimal progression is arbitrary, so that sometimes other numbering systems are employed. This fact caused me to think of the dyadic, or of the double geometrical progression, which is the simplest and most natural. I decided at the outset that it would no more than two characters: 0 and 1... This way [of calculating] should not be employed for the practice of ordinary calculation; but it could contribute a great deal to the perfection of science... Some people have admired in it the surprising analogy between the origin of all numbers out of 1 and 0 and the origin of all things from God and Nothing: from God as the principle of perfection, and from Nothing as the principle of privations or of the voids of essence, without need of any matter independent of God in addition to that.”

Essay on a New Science of Numbers, Gottfried Leibniz, 1701

“Thank-you – you’ve brought me back to my question: what does the Doctor want?”

“To translate all human knowledge into a new philosophical language, consisting of numbers. To write it down in a vast Encyclopedia that will be a sort of machine, not only for finding old knowledge but for making new, by carrying out certain logical operations on those numbers – and to employ all of this in a great project of bringing religious conflict to an end, and raising Vagabonds up out of squalor and liberating their potential energy – whatever that means.”

“Speaking for myself, I’d like a pot of beer, and, later, to have my face trapped between your inner thighs.”

“It’s a big world – perhaps you and the Doctor can both realize your ambitions,” she said after giving the matter some thought.

King of the Vagabonds, Book II of The Baroque Cycle, Neal Stephenson, 2003

When the 17th century theologian and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz wasn’t busy inventing the calculus, or striving to reconcile the Catholic and Protestant churches, or lobbying Russia’s Peter the Great to invest in the spread of scientific knowledge, he was supposedly earning his keep in the employment of Ernst August, the Duke of Hanover. His primary job was to write a history of the Duke’s dynastic family, the House of Braunschweig, itself an offshoot of the ancient House of Guelf.

But Leibniz being Leibniz, this became no ordinary task. As Maria Antognazza tells it in Leibniz: An Intellectual Biography:

“Any really thoroughgoing history, he managed to persuade the duke, needed to begin at the beginning; and the beginning, to someone of Leibniz’s scientific as well as historical perspective, was marked not by the foundation of the Braunschweig dynasty, nor even by that of the Holy Roman Empire, but by the foundations of the world itself. Leibniz therefore proposed a plan to preface the Guelf history with two preliminary treatises. One of these, eventually entitled Protogaea, was to trace on essentially geological grounds the origin of the earth in general and of the region of Lower Saxony in particular. The second was to bridge this geological prehistory with the medieval past by means of an account of the prehistoric and ancient inhabitants of Lower Saxony and their roots in the great migrations of peoples traceable above all through the comparative study of languages -- or, as he put it in April 1691 to Huldreich von Eyben, through a genetic study of ‘the harmony of languages.’”

Antognazza then delivers a rather sharp editorial contextualization:

“What we appear to have here is further evidence of the incapacity of an encyclopaedic mind to resist connecting everything with everything else and the consequent tendency of all of his projects ultimately to snowball into unmanageable proportions.”

I don’t think I am out of place here to feel personally attacked by Antognazza’s drive-by shooting. Because as I write these words, my laptop is surrounded by an absurd pile of hefty tomes: among them, a translation of the divinatory classic The Book of Changes (Yi Jing), Volume 2 of Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China: History of Scientific Thought, three thousand pages of The Baroque Cycle, Neal Stephenson’s rollicking historical novel about the Enlightenment that is also the greatest fictional investigation of the birth of the computer ever set down in print, and Stanford University professor of Chinese history Tom Mullaney’s recently published The Chinese Computer.

Prior to the arrival of The Chinese Computer, the interconnections between these works had been obsessing me for some time. In The Baroque Cycle, Leibniz and Eliza, the former enslaved woman turned Duchess of Qwghlm, employ the binary long-and-short dashes that make up the hexagrams of the Yi Jing to cryptographically encode secret messages to each other. And it is true, historically, Leibniz was deeply intrigued by the Yi Jing, which seemed to him to reflect the exact same principles at work in his own invention of binary arithmetic. Meanwhile Joseph Needham goes so far as to speculate that the influence of Chinese culture upon Leibniz was instrumental in launching the entire Enlightenment project, which ultimately led to the invention of the computer!

For years, the challenge of straightening out this ball of twine into one coherent narrative has tantalized me with the possibility of a unified theory linking the two main intellectual passions guiding my life; Chinese civilization and digital technology. The publication of The Chinese Computer appeared to offer a timely hook to tell this story.

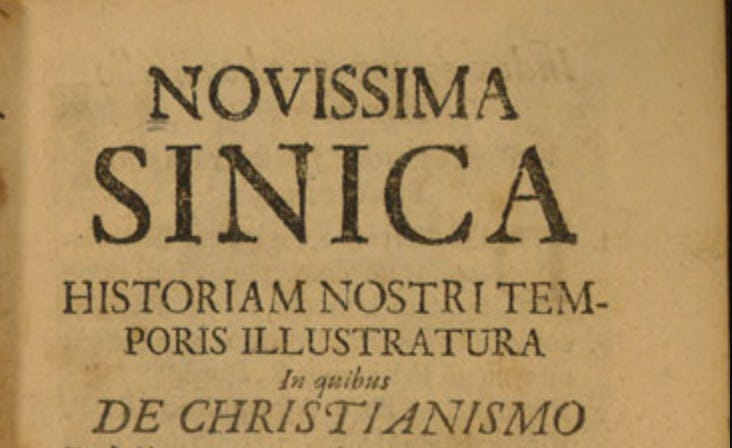

There is no doubt that China fascinated Gottfried Leibniz, who was possibly the most informed person living in Europe on the topic of China at the end of the 17th century. Leibniz corresponded regularly with Jesuit missionaries stationed in Beijing. In 1697 Leibniz even started a journal, Novissima Sinica (News from China), to better acquaint Europeans with the philosophy and history of a civilization he regarded as worthy of comparison to Europe’s.

For Leibniz the benefits of “mutual exchange” offered humanity boons of the highest order. As Francis Perkins tells us, in a letter to the Jesuit Antoine Verjus in 1697, Leibniz wrote that the sharing of intellectual traditions between China and Europe constituted “a commerce of light, which could give to us at once their work of thousands of years and render ours to them and to double so to speak our true weal for one and the other. This is something greater than one thinks.”

Perkins elaborates: “All knowledge expresses God, either directly through our ideas, or indirectly through our expression of a universe which in turn expresses its creator. Through knowledge, perspectives converge, so that learning never threatens either religion or harmony. Guided by the principle that two truths cannot contradict, Leibniz confidently embraces knowledge from China... Leibniz had no fear of accommodating European thought to any truth.”

In this context of discovering the truth, the structure of Chinese characters exerted a particular attraction on Leibniz. He regarded written Chinese as a potential model for his dream of a “universal language” that would mathematically and symbolically represent the totality of human learning. His interest was predicated on a basic misunderstanding of how Chinese characters work, but that’s just a quibble. Leibniz’s ambition is the point: His universal language would be uniquely capable of mathematically settling questions of faith and religion once and for all, which would in turn assist in bringing lasting peace to a Europe torn apart by the sectarian bloodshed of the Thirty Years War.

To a Daoist, seduced by the notion that the totality of the universe is inherently inexpressible, Leibniz’s dream of a language capable of proving the ultimate truths of existence seems a quixotic impossibility tinged with more than a whiff of madness. But here we encounter the most extraordinary contradiction. Leibniz’s abiding genius was his pioneering Enlightenment commitment to rationality. So much so, as David Mungello has noted, that “ironically, [his] attempts to reconcile the increasing divorce of reason from faith led to a synthesis so completely rational and lacking in direct spiritual practice that his ultimate contribution was to the further secularization of European thought.” Leibniz’s indefatigable effort to prove the existence of God became foundational to the scientific and technological revolutions launched by the Enlightenment.

We are no closer today to settling questions of faith and morality in any final sense than we were in the 17th century, but Leibniz can be said to be successful in one sense. The networked computers that link the vast majority of humanity into a web of interconnection are the closest thing humanity has ever created to a universal language. These computers function on an infrastructure of binary arithmetic invented by Gottfried Leibniz. When communicated via digital transmission, every human language, every alphabet or set of ideograms or line of programming instructions, is nothing more than a bunch of ones and zeroes.

Poised at my laptop, with one click of an icon I can change my keyboard input system so that instead of writing in the English alphabet I am 寫中國漢子. I can happily converse in written Chinese via my phone with random strangers who text me from the other side of the world in daft attempts to lure me into crypto scams and related shenanigans. I have access to a wealth of knowledge, a “commerce of light” that surely would have boggled Leibniz. If we’re looking for a “first cause” to explain how this magic came to happen, we need search no further than Leibniz.

Thanks… I guess? Because I probably need not belabor the point that at this present juncture in time the universal language of digital computing may well be argued to have caused more problems than it has solved. Despite our universal ability to communicate with each other, “truth” is more fractured than ever. We have built a cathedral of insanity out of our digital blocks. One would have to imagine that Leibniz would be disappointed at the current state of the world, even if he would have adored the iPhone.

The challenge of tracking how fictional and non-fictional and outright divinatory narratives intersect and contradict and amplify and echo each other in the service of a coherent story about the unified theory of the digital age and China and mutual comprehension carries with it more than just a whiff of madness. I have felt, more often than I would like, as if I have inserted myself directly into a Philip K. Dick novel. Dick’s breakthrough work, The Man In The High Castle, notoriously incorporates The Book of Changes as a major plot device, but was also, according to Dick, itself written via random consultation of The Book of Changes.

But every time I consult the Yi Jing, I end up more confused than before.

The flow, nonetheless, is irresistible.

End of Part I. Read Part II.

Loved this smart and provocative posting.

Francia Bacon(Advancement of Learning, 1606) sought to distinguish between religion and science (“the book of God’s word” and “the book of God’s works”). Since then, as science has advanced, some very smart scientists who are also religious thinkers, recommend keeping the separation in mind. (See, e.g., “God’s Universe” by Harvard physicist Owen Gingerich). Not the Chinese way prrhaps, but a distinction worth thinking about.

Leibniz was quite a guy!