Hermes Trismegistus Enters The Chat

Leibniz, the Chinese Rites Controversy, and Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Technology. Part II of The Universal Commerce of Light

Read Part I.

Gottfried Leibniz was introduced to the Book of Changes by the Jesuit missionary Joachim Bouvet. One of six Jesuit envoys dispatched to China by the French Sun King, Louis XIV, Bouvet was a remarkable man. He arrived in China in 1688, quickly learned to read and write both Chinese and Manchu, and, when he wasn’t translating Western scientific texts into Manchu or setting up a European-style pharmacy in Beijing, found employment as a mathematics tutor to the Kangxi emperor, himself one of more extraordinary rulers to have ever governed China.

Bouvet’s position as a Jesuit missionary with personal access to the emperor made him an active participant in a drama known to history as “the Chinese Rites Controversy.” The whole point, obviously, of sending missionaries to China was to convert the Chinese people to the Christian faith. But within the Catholic Church two main camps disagreed on the best tactical approach towards achieving this end. The members of the so-called “Accommodationist” camp, which included most of the Jesuit missionaries stationed in Beijing, believed that Confucian philosophy was largely compatible with Christian values. They dismissed Daoism and Buddhism as idolatrous superstition, but found much to admire in the teachings of Confucius and the moral values of the literati. Their position was that the strategy most likely to have success in converting the Chinese to Christianity was to stress similarities and downplay differences.

The opposing camp, which included the Franciscan and Dominican missionary orders as well as most of the church hierarchy back in Rome, viewed the traditional rites in which Confucians honored their ancestors and took part in the “cult” of Confucius as pagan heresy. They were hardliners: one could not be a Christian while simultaneously participating in such practices.

Bouvet’s correspondence with Leibniz, and his obsession with the Book of Changes, can only be understood in the context of the Chinese Rites Controversy. While on a return trip to Europe, Bouvet read Leibniz’s Novissima Sinica, which, according to Leibniz scholars, can be interpreted as leaning towards the Accommodationist camp. This makes sense, since Leibniz was always trying to reconcile sectarian division and find common ground across religious and civilizational divides. Impressed by Leibniz’s work, the missionary wrote him a letter and sent him a copy of his own laudatory biography of Kangxi.

The ensuing correspondence continued for years; of particular note is a letter sent on November 8, 1700, just a few weeks after Bouvet had been one of 30 Jesuits petitioning Kangxi to explicitly declare by imperial edict that the Chinese rites were not heathen.

In this letter, Bouvet extols the Book of Changes as “the most ancient work of China and perhaps of the world and the true source from which this nation had drawn all its wisdom and customs." In succeeding letters, he provided a detailed analysis of how the structure of the hexagrams that make up the core of the Book of Changes corresponded neatly with Leibniz’s own invention of binary arithmetic. All of this was in support of a larger Accommodationist argument: the more one could show correspondences between East and West, the more one could make the case that really, way back in the beginning, there was only one true faith – Christian – that had gradually become corrupted over time here and there.

Bouvet, writes the scholar David Mungello “believed that the conversion of the Chinese to Christianity could be accomplished by reteaching the Chinese what had previously been part of their knowledge. Leibniz subscribed to this view, particularly since he himself was working on an arithmetical common denominator for solving general problems of knowledge. One can imagine his excitement when he later discovered the similarities in progressions between the hexagrams and his own binary arithmetic.”

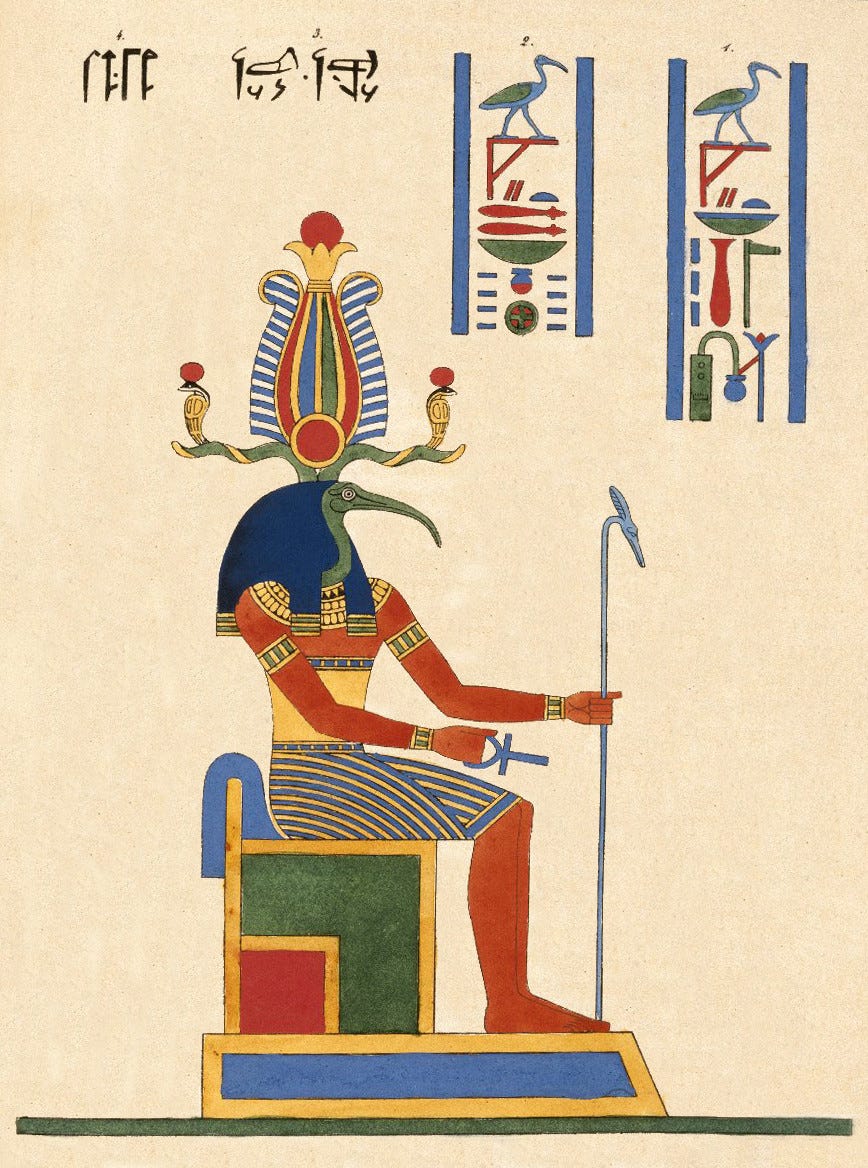

But then things start to get a little weird. Suddenly, Hermes Trismegistus -- “Hermes the Thrice-Greatest” -- a conflation of the Greek god Hermes with the Egyptian god Thoth whom Renaissance-era Christian writers believed to have predicted the arrival of Christianity, enters the chat.

Bouvet’s Accommodationism incorporated far more than just Confucian civil society. In his correspondence with Leibniz he makes a complicated argument that the hexagrams in the Book of Changes were actually the beginning of the Chinese written language (and somehow related to Egyptian hieroglyphics), and that the mythical Chinese figure Fu Xi, who was occasionally credited as being the original author of the Book of Changes, was actually Hermes Trismegistus!

Or possibly Zoroaster. Or maybe even Enoch, the pre-Flood patriarch who was (is?) immortal. Or a combination of all three! It’s all connected!

Leibniz did not respond to this missive.

+++

The historian Joseph Needham called the letter to Leibniz in which Bouvet analyzed the binary structure of the hexagrams in the Book of Changes “an event from which flowed one of the most remarkable examples of Chinese-European intellectual contact.”

As we may later see, Chinese influence was responsible, at least in part, for [Leibniz’s] conception of an algebraic or mathematical language, just as the system of order in the Book of Changes foreshadowed the binary arithmetic. In 1643 Blaise Pascal had constructed the first adding machine, but it was Leibniz who in 1671 conceived the first machine which could be able to multiply… It is not in the least surprising, says Wiener, that the same intellectual impulse which brought about the development of mathematical logic led at the same time to the ideal or actual mechanization of the processes of thought, for both were essentially devices intended to achieve the most perfect precision and accuracy by cutting out human prejudice and human frailty.

From this starting point, Needham embarks on a speculative journey in which “organic” Chinese philosophy is instrumental in shaping Leibniz’s thought and thus influencing the future course of European scientific and technological development.

Now, I am always in favor of stories and recipes that weave stimulation from a mélange of multiple unexpected sources. The hypothesis that Chinese thought influenced Leibniz, one of the wellsprings of the Enlightenment and the intellectual ancestor of the computer, seduced me instantly as a worthwhile topic for investigation. And it’s been a fun ride. I certainly did not expect to meet Hermes Trismegistus along the way, but any day that Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom (and writing and hieroglyphics and science and magic) makes an appearance in a newsletter ostensibly focused on Sichuan food and globalization is a very good day. And I have nothing but respect for Leibniz’s efforts to find common ground and mutual understanding across cultural and religious chasms.

But right as this epic moment of Chinese-European connection was happening, the Accommodationists were losing the Chinese Rites Controversy in dramatic fashion, with negative implications that resonate to this day. In the next installment of this series, we will meet another Catholic missionary who lived in China for many years. His name was Charles Maigrot, and despite abjectly humiliating himself in a face-to-face meeting with the Kangxi emperor, he was the single person most responsible for the defeat of Jesuit Accommodationism and thus also personally at fault for bringing an end to an era of mutual toleration and friendship between China and the Catholic Church.

And to bring this all back to computers and universal languages linking the world together into one common web, which is where I thought I began this story: I will also make the argument that Maigrot is at least partially culpable for the fact that the United States currently bans the sale of advanced semiconductor manufacturing technology to China.

End of Part II. Read Part III.