The Impossible Dictionary of Truth

Or: How everything I knew about hogs in Chinese homes was wrong. The Cross-stitched Pig, Part III

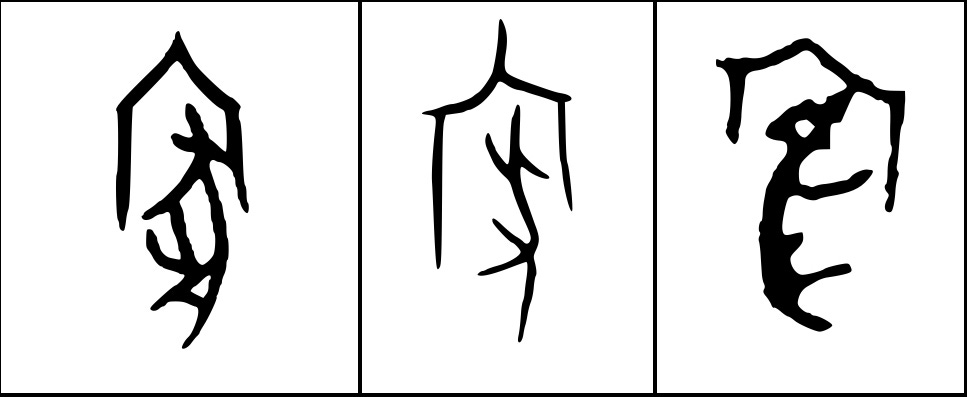

The Chinese word for home is 家 (jia). The traditional deconstruction of the character, dating back many centuries, declares that it is a pictograph, a drawing of a pig under a roof. Home, in other words, is where the pig is.

The World of Chinese explains:

“… [B]y the Shang Dynasty, animal husbandry had already been developed. People had domesticated pigs, sheep, oxen and horses. Because pigs were kept indoors with their owners, having a pig inside the house indicated that it was a place where people also lived; that's why ‘a house with a pig in it’ could be used to write a character that meant ‘the place where people live.”

This supposed intimacy between human and hog, dating back to prehistoric times and embedded in the structure of characters carved into Shang dynasty oracle bones, has been cited countless times as testimony to the transcendent role of the pig in Chinese culture. Pigs were foundational pillars of peasant existence, efficient processors of food waste into valuable fertilizer and cornerstone culinary offerings at the biggest events – New Years and weddings and funerals and birthdays. A pig under one’s roof signified agricultural fertility, economic self-sufficiency, and tasty pork belly.

I’ve been kicking myself ever since I repeated this pop pig psychology in an earlier installment of this newsletter, because if I had checked my notes more thoroughly I would have recalled that I had once read a blog post arguing that the “folk etymology” of 家 was incorrect. And wouldn’t you know it, the author of that post (published 15 years ago!) showed up in my comments.

Here’s his sourcing:

Mark Lewis, in his Construction of Space in Early China, p. 92, says (following Xu Shen) that the character 家, home, is not a pig under a roof, but a child under a roof, as the seal-script hai 亥 looked a lot like shi 豕.

A child under a roof!? Was the thesis of Chinese pig exceptionalism premised on no more than a typo? It was important to get this right: In a newsletter about Sichuan food, getting the facts correct about pork is a matter of existential importance. As a first step, I checked with one of my favorite resources, the Sinologists group on Facebook, asking for clarity. Within 24 hours, John Renfroe, an expert in Chinese paleography and the co-creator of the Outlier Dictionary for Chinese Characters, offered a very different etymology.

According to Renfroe, the top component of the character 家, previously described as “roof,” more accurately conveys the meaning “building.” The bottom part, the piece that in Shang times looked like a pig, signifies nothing more than the sound of the character. In ancient China, so the theory goes, the sound of the word “boar” was similar to the sound of the word “home.” The scribe who first invented a way to write the word “home” did so by combining a component that meant “building” along with a pronunciation clue. No commentary about pig-human cohabitation was implied.

This argument, it should be emphasized, is just one theory among several. Chinese paleography is not a hard science. I subsequently found yet another explanation, put forth by David Keightley, who was one of the world’s greatest experts on the Shang dynasty. A footnote in his book, The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China, states that “jia in the oracle-bone inscriptions probably referred to a temple-palace, and the pig element may have indicated the sacrifices offered there.”

A mis-print, a pronunciation clue, or an act of worship? This is how it so often happens: I go in search of a definitive answer, and I end up more confused than when I started. If I gained clarity on anything, it is of how enormously complicated the origins of the Chinese written language are and how the consensus interpretation of its evolution is in constant flux. This is true now perhaps more than ever. Seemingly almost every day, new discoveries are made of texts carved into bamboo more than two millennia ago, shifting our current interpretations of the classics, introducing new character variants, and generally messing with our heads.

Case in point: for thousands of years, the first line of Laozi’s Daodejing stated that “The Way that can be told of is not an Unvarying Way” (Or: “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao,” Or: “A way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way”). This has long been considered a deliciously subversive thesis statement with which to kick off a philosophical manifesto. But a version of the text discovered at Mawangdui in 1973 revealed a completely different chapter order. What had been the first chapter suddenly became the 38th! Did this undermine the significance of what we thought was an opening salvo or is it even more subversive proof of the basic argument? The Way that can be spoken does not even have a permanent table of contents!

Maybe we will never know what 家 really means. Reading Chinese is hard.

I’m OK with that. Because the upshot of this whole exercise is that I now have a new dictionary to play with, and it fits inside my phone. Not only has this provided me with new proof that reading Chinese is easier than ever, but it is also grist for one of my favorite topics: the question of how technology is screwing with our brains.

“A hard choice confronts the Chinese. If they maintain the quintessentially Chinese system of characters as the exclusive means of writing, it seems certain that many if not most of the people will be doomed to perpetual illiteracy and that China’s modernization will be seriously impeded.”

John DeFrancis, The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy

“One scarcely has to learn Chinese Characters the hard way – by memory or by hand – anymore it seems… Technology for inputting Chinese for electronic communication is improving all the time… As more characters enter digital circulation, the Chinese language is being ever more widely used, learned, propagated, studied, and accurately transformed into electronic data. It is as about as immortal as a living script can hope to get.”

Jing Tsu, Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution that Made China Modern.

“A revolutionary new learners' dictionary for Pleco!”

The Outlier Dictionary for Chinese Characters.

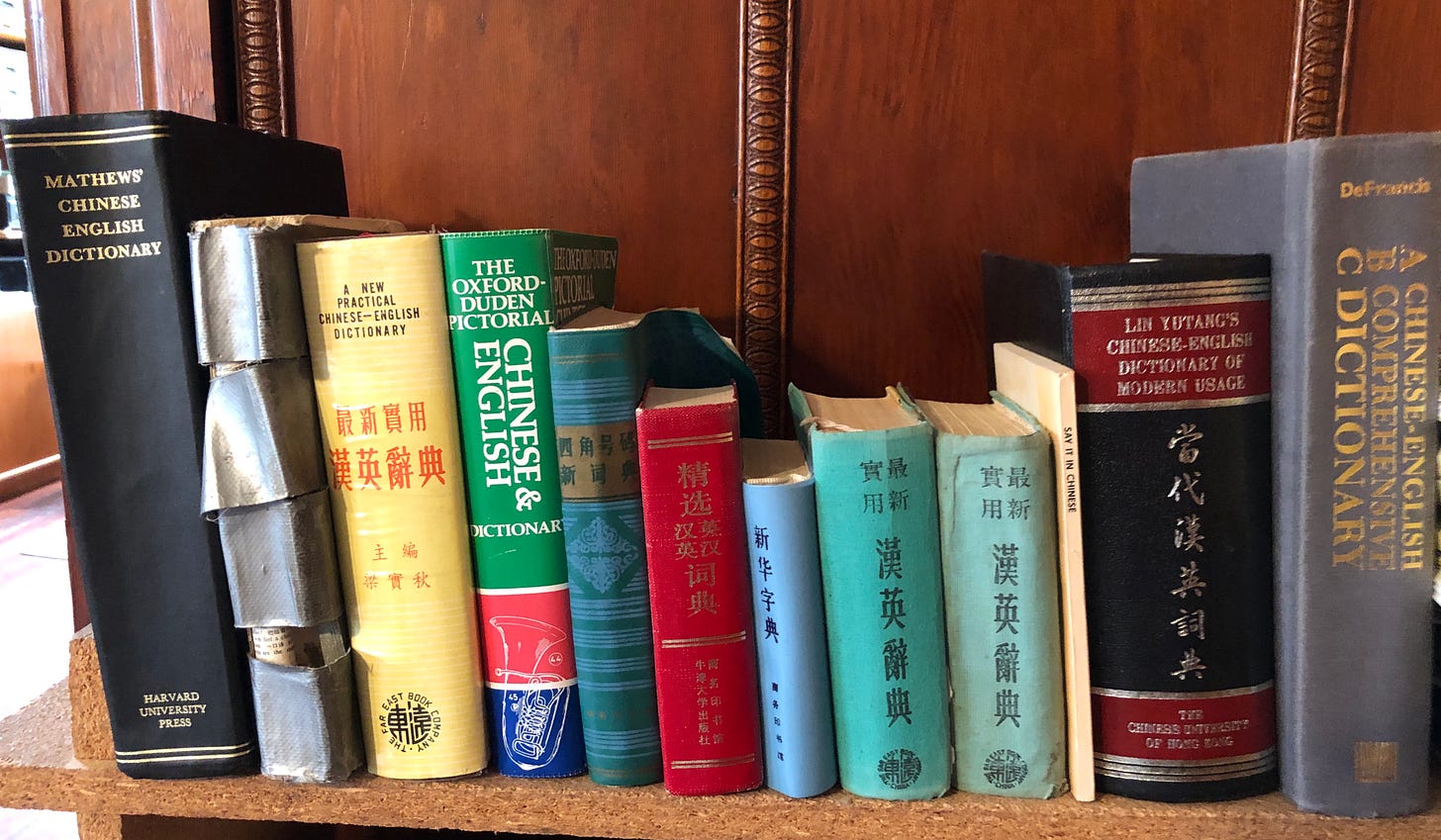

The slippery inconclusiveness that ended my quest for 家 clarity recalled all too clearly to mind the persistent frustration that clouded my first ten-year-long attempt to learn Chinese. The fundamental task of looking up Chinese characters in a dictionary used to be an enormous pain in the ass. There was just no sure-fire way to do it, no alphabetic algorithm that gave you the right answer every time. Characters were a crazy mix of semantic and phonetic components and every rule had multiple exceptions. When confronting an unknown character, my first step used to be to decide which look-up technique offered the best chance of quick success. Should I use the radical system, a somewhat ad hoc method in which Chinese characters had been organized into an index based on their supposed core components? Or should I go with the much more abstract four-corner system, and generate a four-digit number based on the shapes in each quadrant of a character, and then look up that number in an index? Was I dealing with the traditional “complex” characters used in Taiwan, or the “simplified” characters introduced in the latter half of the twentieth century on the mainland?

The whole process was incredibly time-consuming and baffling. No wonder language reformers desperate to respond to the challenges of Western imperialism advocated junking the entire system and moving to an alphabet. Learning to write and read Chinese required devoting countless hours to brute memorization; time that could be better spent mastering the scientific and technological skills necessary to fend off the colonialists.

All that frustration seems like a dream to me now. I haven’t cracked open one of my printed dictionaries since I installed the Pleco Chinese language app on my phone six years ago. Not only does Pleco include optical character recognition and a document reader in which I can get the definition to any character by simply touching it, but it also has an incredibly accurate handwriting recognition system. If I come across a character I don’t recognize, I scrawl it on-screen with my index finger and instantly see definitions from multiple dictionaries. (Pleco has licensing deals with multiple partners; as a user, I choose which plug-ins I’m willing to pay for. The list of choices is always expanding.) Simplified characters, traditional characters – they’re all there. Would I like to hear the Cantonese pronunciation of a particular word? Not really, but I’m delighted that the option exists.

Even though I am not 100 percent convinced that there is an ultimate ascertainable truth about 家, Renfroe and his collaborators made a good enough case that their explanation best fit the available “paleographic, phonological, and archaeological” evidence that I immediately purchased the Outlier Dictionary for incorporation into Pleco. I could see instantly that it would be a Chinese geek’s delight.

The Outlier Dictionary provides information on character structure and etymological history that goes far beyond the simple definitions provided by normal dictionaries. It taps into the deep vein of fascination that has seduced so many students of Chinese into obsession with the written language. A Chinese character isn’t just a word – it’s a symbolic artifact incorporating multifarious aspects of Chinese history and culture into its structure. Every Chinese character is a crossword clue; the puzzle is Chinese civilization. For a dictionary lover like myself, discovering the Outlier Dictionary was like finding a loot box in a fantasy role-playing-game that contained a magic Staff of Semantic Power. My language comprehension abilities were instantly buffed.

Pleco is my favorite digital tool, a sublime distillation of my (often dashed) hopes for the liberating possibilities inherent in a digitally networked universe. I can’t imagine returning to a life without it. The hours I spend every evening reading Chinese texts with my smartphone by my side are some of my most contented. The extraordinary friction that once hampered every move is just… gone.

I mix a drink. I might have a Warriors game on in the background. I look up characters. I engage with another culture.

And of course, my experience is nothing compared to the transition made by the billions of native Chinese who have come of age in the digital era. As the author Jing Tsu observes, despite the complexity of the language, far more people are reading and writing Chinese than ever before. The language reform argument is now mostly moot – China’s modernization is not in doubt, and Chinese characters aren’t slowing anything down.

But there is one under-discussed aspect of all this that ironically proves the reformist argument partially correct. When Chinese users interact with their own language via electronic devices, the vast majority of them are using input systems that merge alphabets with Chinese characters. We are all “writing Chinese” by typing a few letters of an alphabetic system like pinyin and then choosing from a pop-up palette of Chinese characters that match that spelling. It’s fast, it works, and it’s so, so easy, especially when combined with predictive systems that guess the next most likely character you might want to write.

Chinese characters have never been more accessible and this fact extends across the entire span of Chinese civilization. Efforts are well under way to digitize every character that has ever appeared in any medium. Xu Shen, the author of the first Chinese dictionary, the Shuowen jiezi, lived in the first and second century AD, but was forced to come up with his own etymological theories about character derivation without ever having laid eyes on the Shang dynasty oracle bones interred beneath the central plains a thousand years earlier. But now everything that has been excavated in the last century or two is just a click away.

… A vast array of paleographic sources is now represented in digital form, ranging from the inscriptions on bones and shells to those on bronze vessels, seals, pottery vessels, coins, also writings on bamboo and wooden slips, jade and stone tablets, silk, among others. In some cases, a single database encompasses most if not all of the data from a single writing surface, as is the case with the bone and shell inscriptions of the Shang… or writings on the large number of bamboo and wooden slips from the Warring States, Qin, and Han.

--- Newly Excavated Texts in the Digital Era: Reflections on New Resources

At some point, I am sure, all that information will funnel down into my smart-phone. When I scrawl a character onto a touch-screen I will be able to see versions of it carved into bone or inscribed into bronze. I will be able to view the multiple variants that emerged in the era of Warring States, where multiple kingdoms cultivated their own individual versions of the Chinese script, a state of confusion that only ended when the first emperor of the Qin dynasty imposed universal rule, and a universal script.

So what’s the catch?

“Crucially, we found that children’s reading scores were significantly negatively correlated with their use of the pinyin input method, suggesting that pinyin typing on e-devices hinders Chinese reading development… If children use the pinyin input method early and frequently, particularly before reading skills have been acquired, their reading development could be slowed.”

“This pattern of findings indicates that children’s Chinese character-reading performance significantly decreases with the utilization of the pinyin input method and e-tools in general. Pinyin typing appears to be harmful in itself; it interferes with Chinese reading acquisition, which is characterized by fine-grained analysis of visuographic properties of characters. Handwriting, however, enhances children’s reading ability.”

As one might suspect, there has been an extraordinary amount of research conducted in recent years attempting to determine the impact of the digital transition on Chinese literacy. In one of the most cited entries in this literature, China’s Language Input System in the Digital Age Affects Children’s Reading Development, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2012, four brain science researchers at the University of Hong Kong reported research that made what in retrospect seems like an intuitively obvious point. Dependence on digital tools is correlated with degraded performance in reading and writing Chinese without digital crutches.

Classic: It is simultaneously easier for millions to read and write Chinese, but we are also getting dumber and dumber as we come to rely too much on the tools that smooth the path forward. This is a research result with enormous metaphorical power for describing the impact of digital technology on the entire human race. Some thirty years after the release of the Mosaic web browser it is difficult not to review the state of the world and conclude that along with our great digital powers has come great imbecility.

I’ve been uncomfortably wondering for years what effect this transition was having on my brain, and my cursory review of the impact of digital input tools on Chinese language skills did not boost my confidence. Then I read the following passage in Differential Impacts of Different Keyboard Inputting Methods on Reading and Writing Skills, one of the many papers that cited the research on children’s reading development quoted above.

“In a recent fMRI study, Cao and Perfetti argued that reading-writing connection is stronger in Chinese than English reading, and American adults who learned Chinese characters using handwriting practice have stronger brain activity in the left middle frontal gyrus (a brain region found to be important for Chinese reading) than those who learned without handwriting practice.”

The left frontal gyrus is located in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It has been neuroanatomically associated with the development of literacy. There is also research connecting brain activity in this region with the development of complex writing tasks.

I found this reassuring. Because it just so happens that when I sit down at my writing desk to read a Chinese text, I always place a yellow legal notepad to the right of my smartphone. And every single time I am forced to look up a character, I write that character down by hand on my pad. It feels old school and a little ridiculous and my calligraphy is terrible, but I am nonetheless tickled by the notion that that this daily habit might be building brain muscle that boosts my more general writing skills.

I ran this thesis by my mother, who is a retired neuroscientist, and she splashed cold water on it. “I would think it a long leap from the physical act of writing Chinese characters to the purely mental act of stringing English phrases together,” she wrote. “I would be surprised if the two behaviors shared that much neural space. But all exercise is good, physical and mental because there are just general effects.”

I have found much to mull over in her straightforward assessment. The research seems clear in the Chinese case: new digital tools are often short-cuts that get us from point A to point B while skipping out on the necessary exercise that builds cognitive muscle. Surely there is at least a partial explanation here for the profusion of hate speech and conspiracy mongering and flamewars that infest online spaces. When you had to mimeograph your own goddamn zine you took a little more care with your words and you had an incentive not to waste paper and ink on childish histrionics! But now that all friction has been removed from accessing and regurgitating information we are unfortunately free to drown ourselves in Q-Anon bullshit.

But I still can’t accept that my Pleco app is making me dumber. On the contrary! More than any other tool, it has helped me to engage with Chinese culture at a depth I’ve never previously reached.

The authors of another study of students of Chinese theorized that because typewriting Chinese “requires less cognitive and physical work than handwriting…. learners are to some extent free to focus on higher-order thinking activities.”

That’s how I’d like to think of Pleco – a tool that frees space for higher-order tasks such as writing newsletters or tweaking pork belly home fry recipes. It would be nice to believe so. The problem is, higher-order thinking activities are even harder than looking up Chinese characters before the Internet. It’s all too easy to be satisfied with the quick and easy google search that tells you 家 is all about a pig in a neolithic Chinese house. And even though it has never been easier to seek more complicated and nuanced answers, it’s a bit of a trick to accept that those answers will conflict and contradict each other, and that the more you report, the more messy reality will become. I struggle with this every day.

It’s possible that the authors of some of those ancient Chinese texts, shuffling their bamboo slips into an infinite kaleidoscope of new configurations, understood this truth about existence better than we do today. I’m sure they would be shaking their heads in bemusement at the spectacle of someone like myself, who refuses to reconcile his lust for new dictionaries with his conviction that the ultimate truth isn’t knowable, or at least articulable.

Maybe I just need more exercise.

As a Chinese native who’s trying to learn English on my own, I stumble upon this fascinating article about Chinese. It’s really a shame of me never doubt the etymology of the Chinese character 家, which I always thought comes from a pig under roof.

I totally agree that early using of pinyin may have a bad effect on children’s reading skill. So when teaching Chinese to my children I prefer reading the character and displaying the stroke of character to them.

Thanks for this heuristic article.

BTW, there is a mistake about your handwriting in the photo at the bottom of the article. The character 顽 and 损 both have a component of 贝, but you writes 见.

:)

…More than any other tool, is has helped me to engage with Chinese culture…

Typo—“is” should be it.