Dreaming of Sanxingdui

A story about China that celebrates difference, rebukes authoritarianism, and exults in complexity. Part IV of The Annals of Bronze Age Fusion

Read Part I. Part II. Part III.

In January 1945 the French Sinologist Paul Pelliot gave a lecture in New York City to the Chinese Art Society of America. The bulk of his speech focused on updating the audience on how, happily, most French collections of Asian art had survived intact “after four telling years of German occupation,” and unhappily, on the tragedies that befell many of France’s greatest experts on Asia during the war. The lecture included the terrible news that one of France’s greatest Sinologists, the ground-breaking scholar of Daoism Henri Maspero, had been arrested by the Germans after his 18-year-old son joined the French Resistance. Maspero died in Buchenwald two months after Pelliot’s speech, and only two weeks before U.S. troops arrived at the concentration camp.

Almost as a side note, Pelliot observed that in China, the Japanese invasion that forced many Chinese scholars to flee their homes in eastern China and follow the KMT to its wartime headquarters in Sichuan had resulted in a fortuitous development: at long last, the unique qualities of ancient Sichuanese art were getting their due.

“All of us who have studied the ancient history of China have been struck with the fact,” said Pelliot, “that while Sichuan was already in Han times part of the Chinese confederation, it had a culture of its own. Han sculpture in Sichuan has quite a different character from what it has in Shandong; it is more spontaneous and more alive.”

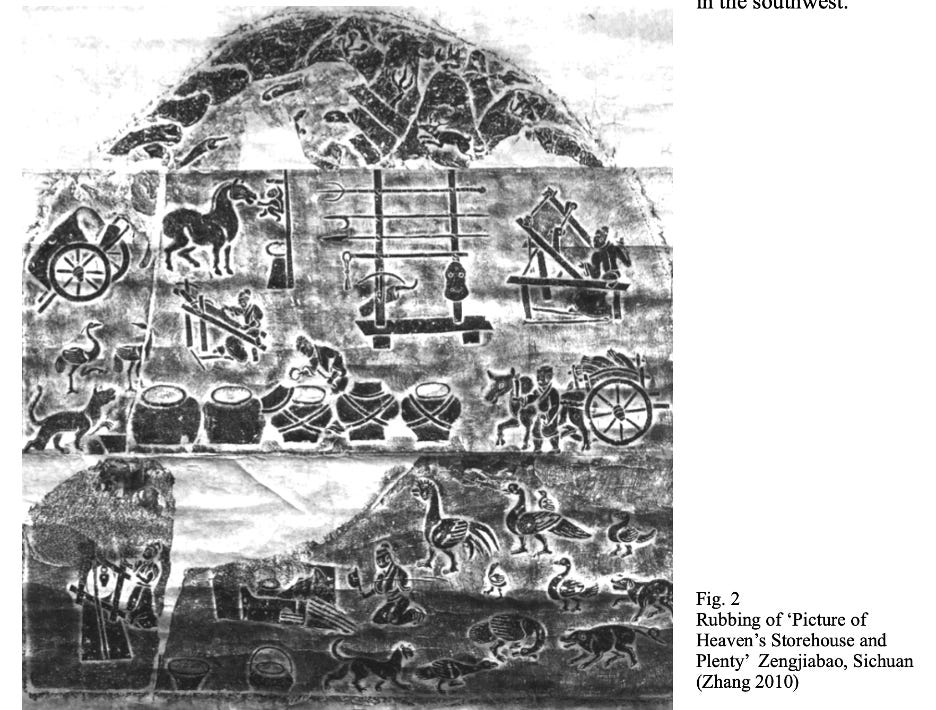

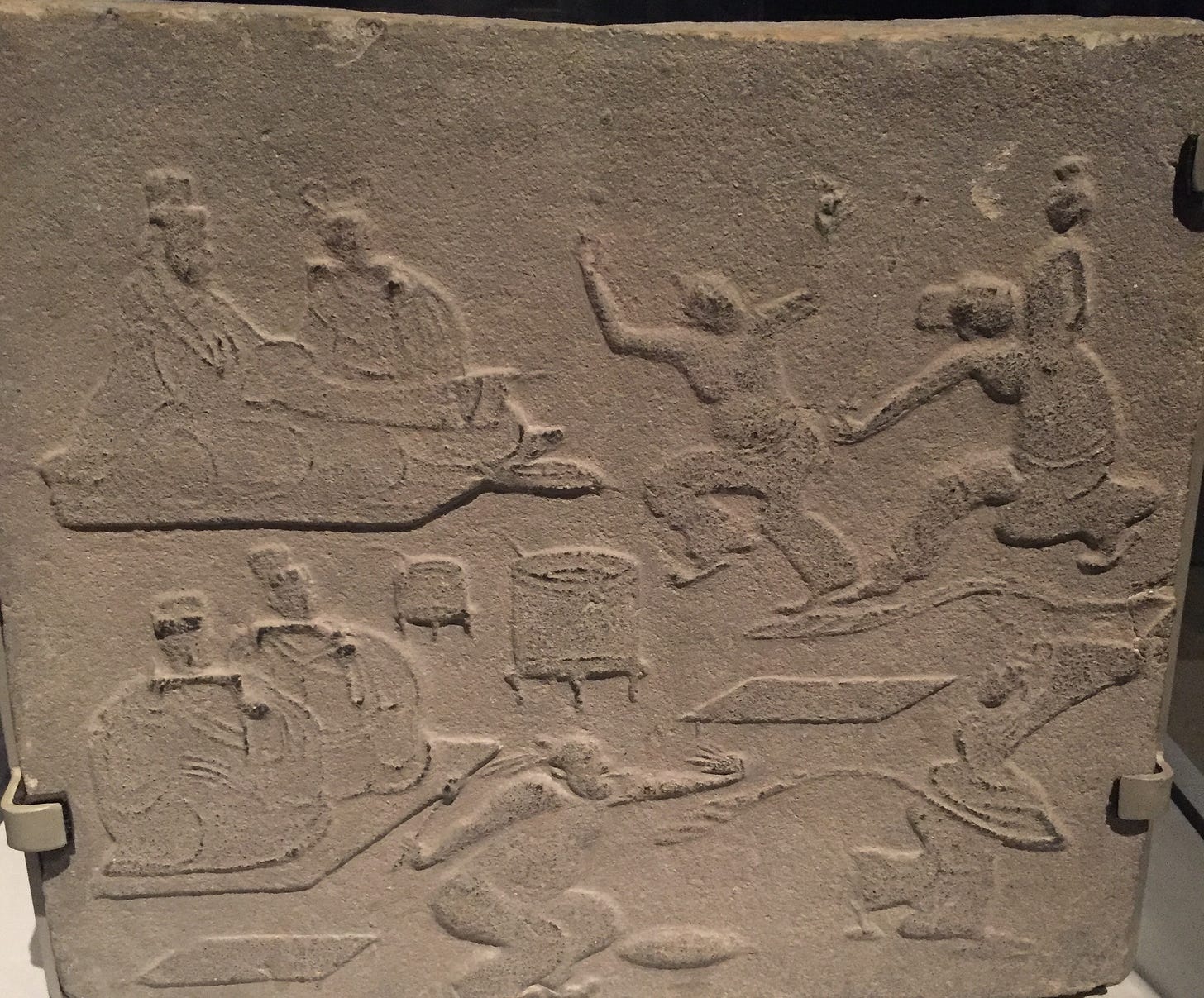

The italics are mine. As expressed through the media of brick tiles and tomb sculptures, Sichuan-style spontaneity was delivered two thousand years ago via depictions of jugglers and dancers and musicians, of birds in flight and fish swimming in rivers, of snapshots capturing live-action images of the daily doings of rice farmers and salt miners and alcohol distillers. The predominant theme: the world as it really is, minus ideological strictures or moralistic admonishments.

According to scholars who have probed the conundrum of ancient Sichuanese identity, all of this art was created in the context of a society that prized intellectual diversity and tolerance. Ancient Sichuan was open-minded and ripe for the fertile exploration of mysticism and mystery. Maybe it is no accident that while the Central Plains locked down all aspects of daily life in a Confucian straitjacket, the frontier province of Sichuan is where Daoist religion – The Way of the Five Pecks of Rice -- burst forth in the second century.

In an essay accompanying a catalog of an exhibition of ancient Sichuan art that toured the United States in the late 1980s, Martin Powers writes that in Sichuan “we find the widest tolerance for those extremes that elsewhere in the empire suffered some degree of exclusion. In the art of Sichuan there is room for you and room for labor; there is lust for money and thirst of knowledge; there is a place for exactitude and a place of exaggeration; most importantly, there is a tolerance for the ordinary and even the ugly.”

There is even room for depictions of sexual affection; something that one just doesn’t see elsewhere in China at this time. Lucy Lim, the editor of the catalog, Stories From China’s Past, notes that one “of the most surprising finds among the Sichuan archaeological materials are representations of intimate scenes in which a man and woman are embracing and kissing.”

Some of these depictions are relatively chaste.

Some, less so:

And some are outright pornographic:

“These unusual Han reliefs seem to epitomize the Sichuan artists’ open and honest acceptance of life in its various aspects and the joy they took in human relationships,” writes Lim.

“The Sichuan scenes,” writes Michael Nylan, in her essay The Legacies of the Chengdu Plain, “rather than picturing eternal and unchanging time, typically seek to give the viewer a sense of momentary time, which necessitates, in turn, a quite different relation to the larger community and cosmos….the ideal was to exult in a free and easy integration with one’s soulmate or with nature itself in order to immerse oneself in the pleasurable insights that can come only from a close personal connection with someone or something else… During the Han, it is first and only in the art of Sichuan that we have human figures placed naturally within a landscape that reminds us of the inevitable processes of change and transformation.”

I must admit to being unprepared for the sight of monkeys cavorting in the canopy above fornicating adults when I chanced upon the brick tile pictured above while visiting a museum in Chengdu four years ago. Up until that point I knew nothing about Sichuanese sexual mores during the Han dynasty. But the viewing spurred some questions whose answers I have been chasing ever since. How and why did this free and easy spontaneity come to pass? What made Sichuan so special? And what, if anything, did any possible answers have to do with Sichuan cuisine, today?

Situated in the upper reaches of the Yangzi River in southwestern China, the Sichuan Basin’s geography may be characterized as “qualified isolation.” The land is marked off from the outside world by land barriers, with mountains or high plateaus on all sides. Against this forbidding topography, however, waterways afforded by the Yangzi River and its tributaries, and trails along mountainsides, often precipitous, offered routes of communication. Thus while the land barriers isolated the Sichuan Basin, severely limiting communication, rivers brought communication from all directions. This qualified isolation probably helped shape the course of Sichuan’s cultural development. The rise of distinctive Neolithic and bronze-using cultures in the Chengdu Plain may well have depended crucially on the combination of geographical isolation and far-flung contacts. The plain was isolated enough to foster the development of native cultures and escape being overwhelmed by any one outside influence, but open enough to be stimulated by outside contact.

Jay Xu, The Sanxingdui Site: Art and Archaeology

Sichuan exceptionalism flourished long before the sculptors of salacious brick tiles plied their trade during the Han dynasty. More than a thousand years earlier the Sanxingdui civilization rose and fell, an amazing fluorescence of art and social complexity that is never mentioned in the ancient Chinese historical record, and that archaeologists only started to appreciate after what Jay Xu calls “one of the strangest discoveries in the history of Chinese archaeology,” the unearthing, in 1986, of two pits filled with an extraordinary array of bronze, gold, stone, ivory and jade items. The pits were near a trio of rolling terraces known locally as the “three star mounds” – Sanxingdui.

Jay Xu is currently the director and CEO of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. In a previous job, as curator of Chinese Art at the Seattle Art Museum, he organized a magnificent exhibition of art from Sanxingdui that was memorialized in a gorgeous catalog: Ancient Sichuan: Treasures of a Lost Civilization. The quote above is taken from his 2008 dissertation, which to the best of my knowledge encapsulates the most state-of-the-art analysis of Sanxingdui available at present in English, although it is fast being rendered hopelessly out of date by the flood of new discoveries made at Sanxingdui over the last two years.

I’ve read more than a few dissertations; rarely do you see the text littered with the kind of adjectives Xu deploys to describe the items dug up from the Sanxingdui pits: “astonishing,” “shocking,” “staggering,” “the likes of which had never been seen before in Sichuan or anywhere else.”

The entire history of Chinese archaeology had to be rewritten. In the late second millennium B.C. the only metropolis in all of East Asia that matched Sanxingdui in size was Zhengzhou, the main city of the Erligang culture, which itself was the Central Plains antecedent to the Shang dynasty. Sanxingdui obliterated the notion that there was a single trunk of Chinese culture rooted in the Central Plains. It distinguished itself with its unique bronze artistry, its profusion of artifacts made from gold, and its mysteriousness. Most of the items found in the pits were burned and smashed into pieces before carefully being laid down. But no one knows why.

At Sanxingdui’s peak, roughly congruous in time with the reigns of Wu Ding and his consort Fu Hao of the Shang dynasty at Anyang, there is no evidence to be found of human sacrifice and no ding cauldrons – that ultimate symbol of state authority in the Central Plains – are buried in the pits. Sanxingdui was different.

The distinct “otherness” to Sanxingdui imagery enraptures both the Western and Chinese eye. But Jay Xu makes clear that despite its singularity Sanxingdui was nevertheless in contact with and influenced by other contemporaneous Bronze Age cultures in East Asia. Notably, Sanxingdui artisans did not invent bronze metallurgy; they borrowed techniques first perfected by the Central Plains Erlitou culture. Some pottery styles seem to have been influenced by civilizations emerging further south down the Yangzi river. Similarities can also be seen with artifacts produced in the north, across the forbidding Daba mountains.

This is Xu’s “qualified isolation.” Yes, the road to Shu is hard, but it is not impassable.

“It seems that Sanxingdui absorbed successive innovations from outside while developing its own distinctive traits,” writes Xu. “Ultimately we must credit the Sanxingdui artists with considerable originality and inventiveness… [but] “even though the contents of [the pits]… are astonishingly original, leaving no doubt that they represent a material culture radically different from that of the Central Plain or anywhere else, traces of interaction are discernible.”

So everything was connected, but Sanxingdui was still singular.

Four facts about early Chengdu stand out in every narrative: its wealth, its diverse population, its favorable strategic position, and its advanced industrial capacity. All these factors enabled, even stimulated it to pursue major innovations. On the economic front, Chengdu was the most fertile of the three breadbaskets for the early empires. The soil was good, the rainfall reliable, the water temperate, and the irrigation systems extensive, so that the Plain enjoyed a long and productive growing season, with the average yields from paddy rice land an estimated ten to fifteen times higher than elsewhere. By Western Han times, local agriculture had already been intensified far beyond subsistence needs. Of the five most valuable processed products of the later Chinese agricultural economy -- textiles, lacquer, tea, sugar cane, and paper -- the Chengdu Plain was already famous for the first three in the early empires. It was moreover one of the richest areas in China in mineral and plant resources… Commercial fishing, animal breeding, and natural gas production further enriched the economy. Small wonder that the area was nicknamed "Heaven's Storehouse" and endowed with a sacred geography.

Michael Nylan, Legacies of the Chengdu Plain.

Sichuan’s singularity did not depend merely on its “qualified isolation.” During both the Han and the Tang dynasties Chengdu was one of the richest and most populous cities in the empire, rivaled only by the capital, Changan. The relative ease with which the good life could be secured in Sichuan was recognized early on by Ban Gu, a Han dynasty historian who lived in the first century A.D.

“The climate in the basin is mild and the area enjoys a long growing season…. The people eat rice and fish, and have no worry about famine years.”

However, for an orthodox Confucian like Ban Gu, the good life was an invitation to bad habits.

“Since the common folk do not suffer hardships, they are easy-going and profligate, weak and mean.”

In the context of the historical yin-yang dynamic between the Confucian emphasis on order and Daoist inclinations to let one’s freak flag fly, it is instructive to witness this positioning of Sichuan values as counter to state-sanctioned Confucian morality all the way back in the first century AD. The claim that there was an geographically-induced Sichuan character had enormous lasting power. Two thousand years after Ban Gu’s side-swipe, the L. A. Times quoted several Sichuanese scholars making almost exactly the same argument, minus the Confucian sneering, in a 2006 article positioning Sichuan as China’s hardest partying province.

“But the leisure of Chengdu people is completely different; it’s in their bones,” says Luo Xinben, a professor at Southwest University for Nationalities and an expert on gambling. Luo and other scholars say Chengdu’s laid-back culture was spawned by its 2-millennium-old irrigation system. Dujiangyan, as it’s called, was built in 256 B.C. to control and channel the waters of the Min River, which had caused floods when torrential waters rushed down the mountains.

“The irrigation system solved almost all the problems in the local agricultural industry and made Chengdu free of any natural disasters for 2,000 years,” says Tan Jihe, a researcher at Sichuan Provincial Academy of Social Sciences. He says Dujiangyan, and Chengdu’s fertile soil and moist air, made it easy to plant rice, corn, potatoes and a rich assortment of citrus and other fruits, giving farmers not only good harvests but also plenty of time for leisure.

“No matter rich or poor, everyone in Chengdu enjoys his life and has entertainment,” Tan says.

Geography is destiny.

The southwest [was] a region marked by a climate of active intellectual inquiry and philosophical heterodoxy during the Eastern Han dynasty. The southwest was far from being a passive recipient of received thought from the center…. The presumption that one school of thought dominated the intellectual discourse, or that there was a blend of ideologies co-existing with little distinction made between them needs re-examination.

As part of her dissertation, Hajni Elias performs a remarkable dissection of the text on a stone stele honoring a first century A.D. governor of the region then referred to as the “Shu Commandery.” She finds it of particular relevance that the stele references both Confucius and Mozi, because by this time in the Han Dynasty, as for as most of the empire was concerned, Confucius was ascendant, and Mozi, another prominent Warring States era philosopher, had become a nonentity. But, perhaps because of Sichuan’s “qualified isolation,” the southwest bucked the national dogmatic trend. Elias positions the “stele’s rich use of literary sources and references that have been taken from multiple influences of thought,” as proof of “a society that appears to have embraced different philosophies, instructions and values to its world order.”

“The stele suggests,” writes Elias, “that in the southwest there was no philosophical orthodoxy or dominance by one school, but on the contrary, the two seemingly opposing and rival ideologies of Ruism [Confucianism] and Mohism advanced side-by-side…. It is evident that, in the southwest at least, philosophies and ideas coexisted and were used and adapted according to society’s needs.”

Bordering Tibet to the West and Yunnan to the south, Sichuan has historically been home to multiple non-Han ethnic minorities. Elias suggests that Sichuan’s openness to “diverse doctrines” was connected to its “multi-ethnic culture and society” and immigrant-infused identity.

And there’s our third piece of the puzzle; Sichuan was isolated and Sichuan was prosperous, and both facts put together made Sichuan a destination for immigrants from elsewhere in China, predating the existence of a written historical record.

To return to Nylan:

But more than merchants and goods moved in and out of the Plain. It was home to a refugee culture in which people from the outside figured largely. Natural wealth and comparative remoteness combined to make it an attractive destination for those fleeing the wars and natural disasters that regularly plagued areas to the north and east…. If the unsurpassed sophistication of the local industries… can be attributed partly to the sheer wealth concentrated in the Plain, particularly in Chengdu City, it also owed much to the number of talented, ambitious, and moneyed men and women who gathered there, exchanging information on techniques of all sorts…

Flash forward to the 1950s, when the Hong Kong food writer Chen Mengyin sketched out a theory about the roots of modern Sichuan cuisine in a column for the Singtao News. In the 17th century, he noted, after an assortment of disasters during the Ming-Qing “transition” had resulted in the drastic depopulation of Sichuan, a process of mass immigration to the province from elsewhere in China took place. The new residents brought their cooking methods and favorite ingredients with them.

As translated by Mark Swislocki in his wonderful book, Culinary Nostalgia: Regional Food Culture and the Urban Experience in Shanghai:

"When [the migrants] arrived in Sichuan,” writes Chen, “at first the dishes they ate were the original hometown flavors, but as the days passed, they and the local Sichuan people came together and understood each other more profoundly. Authentic Sichuan people and the migrants from various other provinces engaged in mutual exchanges of cooking techniques, building on each other other’s strengths and dispensing with the weaknesses. And so, the art of Sichuan cuisine encompasses the strengths of each province."

The most famous instance of this exchange are the chili peppers that Hunanese immigrants brought with them from Hunan, but Chen’s thesis broadens to include multiple different cooking techniques and spice combinations. From this perspective, Sichuan cuisine is fundamentally a hybrid cuisine. Ideological diversity during the Han dynasty; culinary diversity in the Qing dynasty.

I mentioned this thesis to Rowan Flad, an archaeologist at Harvard who has worked on archeological digs in Sichuan, and he told me about research by one of his former students, Jade d’Alpoim Guedes, documenting evidence of the cultivation of both millet and rice in Neolithic Sichuan. This is significant, as China is normally divided between a northern region where millet predominated and a southern region where rice was the main grain; and this division has been taken to signify longstanding cultural as well as culinary differences. But in Sichuan, from the very beginning of agriculture, everything grows and everything goes! Who wouldn’t want to move there?

I call this dish Black Bean Sichuan Fried Chicken. But it is not, strictly speaking, a Sichuanese dish. I first encountered it in Fuchsia Dunlop’s Revolutionary Hunan Cookbook. As Dunlop notes, Hunan cuisine tends to be bolder and more ferocious in its assault on the tastebuds than Sichuanese cuisine. The original version of the recipe includes big chunks of garlic and ginger and scallions and a copious amount of chili flakes and dou zhi, (salted and fermented soybeans) all stir-fried together with chicken nuggets that have previously been flash-fried twice.

This dish was a family favorite from the get go, so much so that it quickly had to be slotted in the category (along with Twice Cooked Pork) of “dishes-that-can-only-be-made-once-a-month.” But then, acting on a spontaneous whim one night, I started tweaking the recipe in search of even more extreme deliciousness. I experimented with breading the chicken nuggets before frying in a mixture of potato starch powder, Sichuan pepper, salt, and cayenne powder. (I got the original proportions for this breading mix from a recipe from Taylor Holliday for an entirely different dish.)

I made a couple of other minor changes which I will detail in a recipe accompanying this post, but for the moment, all I need to say is that this chicken came out so well that it has ruined all other Sichuan chicken dishes for me! (With the important exclusion of chicken wings!) It is too good! It has become my ultimate comfort food, and I’ve made it so many times I’ve come to think of it as an expression of my own identity: Savory, salty, fried, extravagant, a completely ridiculous dish to make for one person and yet I do so all the time.

Sichuan pepper is of course indigenous to Sichuan as far back as we have records – it is one of Sichuan’s primary contributions to the rest of Chinese cuisine. Nobody really knows how long ago the Chinese started salting and fermenting soybeans, but samples were found in the tomb of a Han dynasty noblewoman in Hunan that date back to the second century. The chili, again, was a relatively recent arrival.

I can’t tell a story about any of these ingredients that involves my own ancestors or cultural traditions. But I have decided that the mix-and-match experimentation that resulted in this dish mirrors the more-or-less accidental fusion of ingredients and cooking methods that resulted in modern Sichuan cuisine. So, in my head, I am just one more immigrant to Sichuan, embracing spontaneity, striving for tolerance, open to mystery, seeking free and easy integration with all things (and especially the spicy fried things.)

Since the spring of 2020, Chinese archaeologists have unearthed more than 13,000 new objects from six new pits at Sanxingdui. The current operation is a far cry from the accidental discovery of the original pits, “K1” and “K2.” As noted in one of the very few official reports about the dig, these days Sanxingdui excavations involve “sophisticated and advanced analytical techniques.”

Four cabins were built over them to maintain consistent temperature and humidity for the excavation. In addition, an on-site laboratory was established to ensure that artifacts were protected immediately upon excavation. Excavation was spit based and carried out using 300 × 300mm and 0.5 × 0.5m grids, dependent on each pit’s size, with each excavated spit measuring 50–100mm in depth. All excavated soil was collected and recorded. In addition, each spit was 3D scanned once completed and a 3D model was created using Agisoft Metashape Pro v1.5.0. Polymer bandages were used to extract fragile organic evidence, such as ivory, which was removed to the laboratory for further cleaning.

Travel restrictions since the pandemic seem to have left Western archaeologists mostly in the dark as to how the new discoveries support or contradict existing theories about the Sanxingdui civilization, but within China, the ongoing dig has been a national sensation, with live prime-time broadcasts of archaeologists hip deep in the pits watched by millions.

Very little is known about how the people of Sanxingdui might have been ethnically or linguistically connected to the peoples of the Central Plains. There isn’t even any good evidence that the region we now call Sichuan was ever part of the Zhou hegemony. Sichuan’s incorporation into “the Chinese confederation” came by force, when the Qin invaded in 316 B.C. But none of that makes any difference inside of China: to Chinese archaeologists, state propagandists, and, one assumes, the vast majority of those watching televised archaeological updates, the history of Sanxingdui is part of the history of China.

A typical formulation describing how Neolithic and Bronze Age discoveries in Sichuan fold into a narrative of “Chineseness” runs like this: “These finds have helped to support the theory of a singular Chinese civilization arising from many sources.”

The images of Sanxingdui artifacts featured in a present day lightshow on the streets of Chengdu that I kicked off this series with would seem to support such a theory. Sanxingdui, the Shang, the jade-carving mastery of Liangzhu – everything gets mashed up as “China,” today. But there are some obvious dangers waiting for anyone who follows the path of singular “Chineseness” too far. Not the least of which is that similar arguments are deployed by the state to argue that Tibet and Xinjiang are inseparable from an essential “Chinese” nation, and they provide the ideological backdrop for relentlessly rooting out religious beliefs or local languages and customs whose mere existence challenges the inviolability of a unitary Chinese civilization.

From an outsider’s perspective, this is where it gets complicated. Because the more I look at Sanxingdui, the more I see something that is not Shang. The more I learn about a tolerant, diverse, and super-sexy Han-dynasty Sichuan, the less I recognize 21st century mainland China. I don’t think I need to overly belabor the point that the government of the People’s Republic of China does not welcome the clash of conflicting philosophies or even know what the word “tolerant” means. On the contrary, Xi Jinping seems existentially terrified by anything that remotely resembles free-thinking dissent, marching in ominous solidarity with authoritarian dictators all over the world and more than a few MAGA politicians in the U.S. For something closer to the free and easy spontaneity that characterized ancient Sichuan today, we have to look across the Taiwan Strait, to a free and boisterous democracy where Dao de Jing-quoting government officials make it abundantly evident that they are not afraid of diverse points of view.

My point here is not to say that ancient Sichuan is not China, but rather that ancient Sichuan tells a different story about what China is or could be than what the powers-that-be want to be told.

But we get to choose what stories we tell.

I learned this anew while researching this series of posts, when I encountered yet another passing reference to Zhuangzi’s story about the master butcher Cook Ding. As regular readers are likely aware, the story of how Cook Ding never has to sharpen his cleaver because of his understanding, built from a lifetime of practice and mindfulness and intention, of how to cut only in the “thin spaces,” is a foundational guiding theme for The Cleaver and the Butterfly.

But I’m always ripe for re-contexualization. And after I read a footnote observing that the ox that Cook Ding was carving was likely a sacrificial animal destined for use in a royal funeral rite, I realized that the ultimate destination of the carved meat produced by Ding was undoubtedly one of the grand ding cauldrons that I’ve spent so much time and space in this four-part series contemplating. I followed the footnote back to an essay by an Italian scholar, Romain Graziani, When Princes Awake in Kitchens: Zhuangzi’s Rewriting of a Culinary Myth, that I had actually read six or seven years ago, but hadn’t understood very well because at that time I didn’t know anything about the significance of ancient Chinese funeral rituals in state formation and social stratification.

For years I’ve regarded Zhuangzi’s “knack” parables, of which Cook Ding and the Ox probably is the most famous example, as clever set pieces that Zhuangzi deployed to say the kind of things that can’t be said, to describe the Dao that can’t be described. But according to Graziani, the story of Cook Ding is also a critique of the whole structure of state ritual and power inherited from the Shang and the Zhou. Cook Ding knows that living his best life does not require seeking ratification from his ancestors by succoring them with the biggest ox and the biggest cauldron around, but rather is fostered though nurturing his own inner life and creativity.

Zhuangzi presents a character who influences his lord's mind directly through an informal explanation of his craft…. the personal experience of Cook Ding as it is told to the prince helps to undermine the values associated with the kitchen on the one hand and the sacrificial altar on the other; to separate the human relationship of food preparation and nourishment which is at the origin of the ritual from any possible moral or ritual connotations… Zhuangzi therefore outlines a new relationship between physical nourishment and self-cultivation… Ding’s base task of butchering is transformed into refined artistry…. the massive, inert presence of the ox becomes an opportunity for play and easeful manipulation… his handling of the knife does not serve to symbolize virtuous talents such as moderation and impartiality, but rather illustrates his capacity to move effortlessly through the difficulties of any given configuration.

As a writer and a cook, I initially embraced Zhuangzi’s cleaver story because it struck me as a powerful metaphor for how to practice my own chosen crafts. I started trying to tell that story. But now I see that there is another story to tell, a story that connects Zhuangzi’s cleaver to a critique of exactly the kind of overbearing Chinese authoritarianism that never seems to go out of style, a story that connects me to the free and easy spontaneity of ancient Sichuan while rebuffing all those tin pot dictators attempting to secure power by demonizing trans people or censoring black history.

When I dream of Sanxingdui, or imagine myself in the refugee enclave of ancient Chengdu, surrounded by lively artists and debating philosophers and hustling immigrants in search of a better life, I dream about celebrating otherness and complexity.

And I dream of birds in flight. Because one thing we do know about both the people of Sanxingdui and the artists of Han dynasty Sichuan is that they really had a thing for birds. So I say: less Shang; more Sanxingdui; less order; more chaos; less essentialism; more difference.

And a bronze bird; instead of a holy cauldron.

Another great writing!