A Storm of Sichuan Butterflies

During the Tang Dynasty, a story was told of a chef "who could chop so thinly that the slivers would blow up into a current of air. On one occasion, it is said, a pile of them formed into a storm, turned into butterflies, and flew away."

I stumbled on this gem of magical realism while reading the chapter devoted to the Tang era in "Food in Chinese Culture," the English-language starting point for all serious explorations of the deeper meaning of Chinese cuisine. What a fantastic and wonderful way to imagine the cook at work!

The unexpected juxtaposition of the cleaver -- hard, sharp, hefty -- with the butterfly -- fragile, transient, as light as air -- makes the anecdote resonate on a visceral level. But even more satisfying is the Daoist symbolism. My favorite philosopher, Zhuangzi, employed both cleavers and butterflies in his effort to elucidate the Way.

In his parable Cook Ding and the Ox, a master butcher explains to an awestruck lord who has just watched him dismember an entire animal with superlative skill and ease that his technique, actually, can't be explained in any kind of algorithmically repeatable detail. It is, instead, a knack derived from years of mindful attention to his hands, his knife, the meat. His mastery, his ability to find the "thin spaces" in the ox's joints with the thin blade of his knife, is so great that in nineteen years he has never even had to sharpen his cleaver once. (A hack cook, he notes, has to grind his knife anew every month!)

As for butterflies -- Zhuangzi is probably most famous the world over for a single paragraph in which he recounts waking up from a dream in which he was a butterfly, "flitting and fluttering around, happy with himself and doing as he pleased," but then not knowing, in the cold light of dawn, "if he was Zhuangzi who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuangzi."(Translation by Burton Watson.)

Between Zhuangzi and a butterfly there must be some distinction! This is called the Transformation of Things."

The butterfly, writes Jung H. Lee, an associate professor of religious studies at Northeastern University, in The Ethical Foundations of Early Daoism, embodies Zhuangzi's understanding of the "qualities and virtues of the Way itself."

"To begin with, we can say that a butterfly possesses a light touch, an easiness of movement, a freedom in its behavior -- a butterfly flitters and floats and does not seem to have a care in the world. Applied to a Daoist adept, what Zhuangzi seems to be advocating is a kind of existential freedom in one's relationship with the world, becoming unattached and carefree in regard to things, people, and social boundaries. Second, a butterfly is non-aggressive, non-predatory. The Daoist sage, like the Way itself, is supposed to assume an attitude of passivity and non-resistance.... Third, a butterfly's life cycle embodies transience and impermanence. A butterfly surrenders without protest, unlike human beings, to the process of living and dying as mere episodes in the endless cycles of heaven and earth. And finally, the different stages of a butterfly's existence illustrate the character of transformation. From egg to larva to chrysalis to an adult, the butterfly dramatically alters its shape and form in a continuous process of transformation and change..... All of these qualities and virtues... exemplify the sagely existence of the Daoist spiritual ideal, and this is what I take to be the message of Zhuangzi's dream -- to embody transformation is to embody the Way itself."

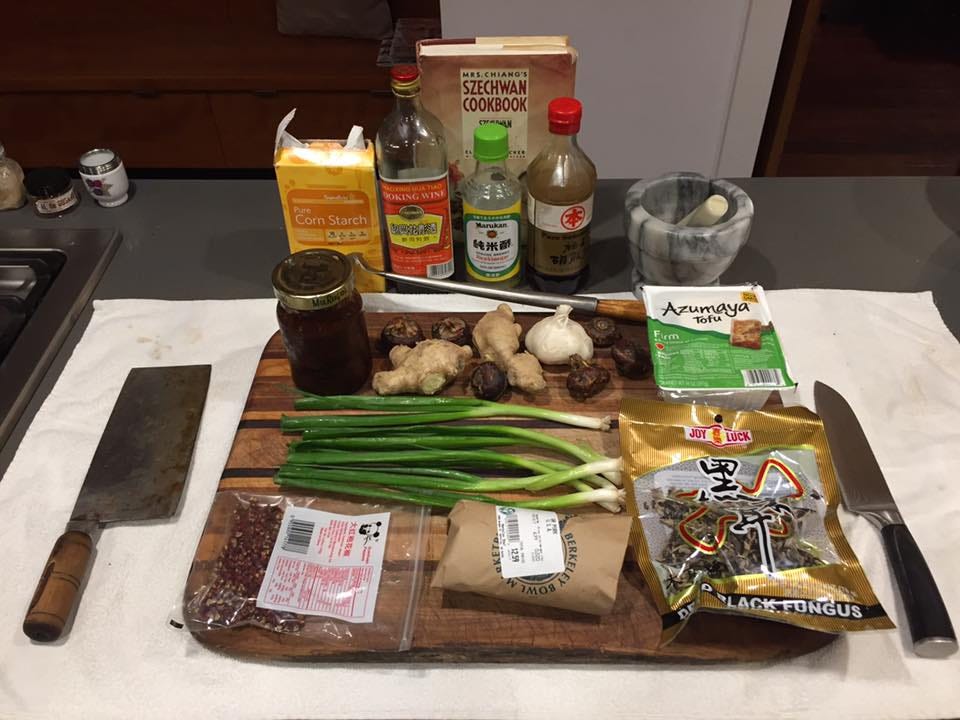

Cooking is fundamentally about transformation; it is its own species of Daoist alchemy. After the chopping and mincing and marinating, the boiling and stir-frying and steaming, those ingredients on the chopping block become something else. It's a miracle every time. As I have over the years learned to leave the algorithmic dictatorship of the recipe behind and trust my own spontaneous-but-rooted-in-hard-won-experience impulses, I have been delighted to witness my own ongoing transformations. I now see the act of cooking as Daoist practice. When I ransack the fridge for a spur-of-the-moment fried rice dish, cleaver in hand, is when I feel most attuned to the Way.

"People who really know what they are doing," writes A.C. Graham in Disputers of the Tao, "such as cooks, carpenters, swimmers, boatmen, cicada-catchers, do not go in much for analyzing, posing alternatives and reasoning from first principles, they no longer even bear in mind any rules they were taught as apprentices; they attend to the total situation and respond, trusting to a knack which they cannot explain in words, the hand moving of itself as the eye gazes with unflagging concentration."

Pretty much the first rule of Daoist philosophy is that if you try to say exactly what the Way is, you are getting it wrong. The recipe for Sichuan fried rice is not the totality of Sichuan fried rice. So even just this attempt to explain what the title of my project, The Cleaver and the Butterfly, so reeking with Daoist memes, is all about seems fraught with certain peril. But I cannot, will not, let go of that glimpse of the Tang dynasty master chef, wreaking her sublime marvels.

I dream of a storm of Sichuan butterflies.

(Front cover illustration of Disputers of the Tao)