One Wing To Rule Them All

Szechwan chicken wings, Warriors basketball, cultural imperialism, and the Dao. Part I

The following story was originally conceived as a celebration of two of my favorite things: Szechwan chicken wings and the Golden State Warriors. I also wanted to weave in some thoughts about China’s venerable love affair with the game of basketball. But then, in late October, Enes Kanter, a backup center for the Boston Celtics, wore a pair of sneakers to an NBA game that mocked China’s supreme leader Xi Jinping with images of Winnie the Pooh’s disembodied head.

This complicated the narrative.

+++

“It is, I think, the greatest eating pleasure in the world.”

Ellen Schrecker, co-author of Mrs. Chiang’s Szechwan Cookbook

Step I:

Marinate the chicken wings in a mixture of ground, toasted, Sichuan peppercorns and salt for two hours.

If tip-off is 7:10 p.m. the Sichuan pepper salt must be prepared no later than three o’clock. The three-stage process involved in making Szechwan Chicken Wings -- marination, steaming, deep frying -- requires a minimum of four hours.

During this time much else can be accomplished. Deviled eggs, shrimp-bok choy skewers, cheese puffs, scallion pancakes, red cooked pork belly... The menu varies according to my whims and expected attendance. If the Warriors are facing a crucial playoff game, smoked baby back ribs with a honey mustard glaze are probably also in the mix.

But all the other menu items are froth. Szechwan chicken wings are the foundation. Szechwan chicken wings bring all the basketball fans to my yard. Szechwan chicken wings are how I honor my fandom for the Golden State Warriors, who for the better part of the last decade have come the closest of any professional sports team in the United States to exemplifying core Daoist principles. Their sublime read-and-react, share-the-ball, spontaneously collective style of play is impossible to capture in an algorithm but manifestly in tune with the primal order of nature. I have no doubt: Zhuangzi would be a Steph Curry fanboy.

The least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief that a man’s body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection and then used for the protection of the weak, the advancement of all righteous cause, and the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men.

Thomas Hughes

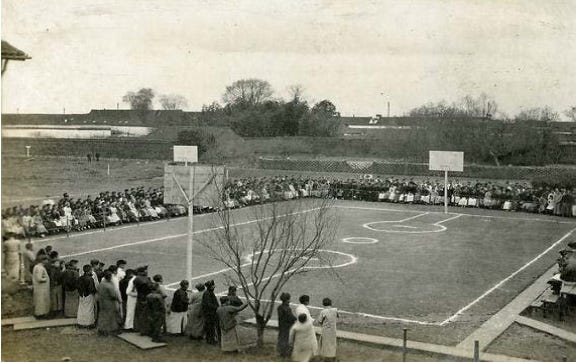

Basketball and China are old soul mates. YMCA missionaries introduced the game to the treaty-port of Tianjin in 1895, just four years after the sport was invented by James Naismith in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Basketball’s China debut was a missionary ploy to win converts to the Christian faith. The YMCA was a leading proselytizer of the 19th century evangelical fad for “muscular Christianity” -- a phenomenon that played a significant role in the growth of modern competitive sport across the entire world.

As described by Zhang Huijie in her dissertation, Missionary Schools, The YMCA and The Transformation of Physical Education and Sport in Modern China (1840–1937), “The basic premise of Victorian muscular Christianity was that taking part in sport could contribute to ‘the development of Christian morality, physical fitness and a ‘manly’ character.” In keeping with the guiding principle -- the belief that a buff body brought one closer to Jesus -- Naismith’s goal at the Springfield YMCA was to solve the problem of how to keep young men fit when forced to stay indoors through the winter. Thus: basketball.

The equation of fitness with Christian moral fiber became a big deal in Victorian-era English public schools and spread outward from there as a kind of ab-hardening virus promulgated by the metastasizing British Empire. There was more at play than just six-packs and religious indoctrination. According to one of muscular Christianity’s “celebrated exponents,” the Victorian lawyer Thomas Hughes, who is probably most famous for authoring Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the movement was designed to “‘infuse Anglicanism with enough health and manliness’ that in turn could ‘make it a suitable agent for British imperialism and increase the health and wellbeing of the nation and all British subjects.’”

Rarely is the historical context quite so stark. Basketball’s introduction to China was a definitive act of cultural imperialism.

Consequently, one might expect that a resurgent China would have swiftly rejected the game as just one more loathed piece of detritus from the “century of humiliation.” Today, China will not so much as allow a Bible app on an iPhone. The antipathy generated by the legacy of the “unequal treaties” that protected missionary activity in ports like Tianjin is still very much alive.

But basketball found a home in China. The KMT generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek was a baller, (although according to contemporaneous reports, he was an asshole on the court). Zhu De, the Sichuan-born general who organized China’s Red Army and was a leader of the Long March, was so passionate about the game that, according to one anecdote, he and his fellow bball-mad officers would strategize potential offensive actions based on whether there was any chance to seize precious basketballs from a defeated enemy.

Basketball even survived the Cultural Revolution, when Chairman Mao strove to eradicate nearly every trace of foreign ideological contagion. In his memoir, Son Of The Revolution, Liang Heng recounts how his 6’ 1” height made him so desirable as a basketball player that party officials were willing to ignore the suspect political status of his family even as the Cultural Revolution raged. Good food, work permits, residency permits -- they all flowed from basketball.

“Our middle school won the county championship, and we went to play in the intercounty district wide meet. I had never had so much to eat in my life. For fifteen fen a day, there was meat, fish, soybean milk, porridge, dumplings.... One morning I ate fifteen mantou for breakfast.”

Today, basketball is big business in China; proof that even egregious acts of cultural imperialism can be culturally appropriated.

The reasons why China embraced basketball trace back to the country’s own socially Darwinist preoccupation with the perceived effeminacy of Confucian bureaucratic culture and some intriguingly suggestive concordances between the essence of basketball and both Chinese philosophy and Maoist ideology. But post-Mao, the story gets even more twisted. A second wave of cultural basketball imperialism in the 1990s, led by the NBA’s at first extremely popular replacement of missionary evangelism with late capitalist brand globalization, has since evolved into a powder keg of political sensitivity in which a single tweet can detonate multi-million dollar infernos. Basketball, as a sport, exudes the sophisticated simplicity of the Dao. Basketball in China, as a platform for cultural and commercial exchange, is very, very complicated.

But before we get to all that (and Enes Kanter’s shoes!), we have to take a break. It’s time to steam the chicken wings.

Step II.

Arrange the chicken wings in a steamer, cover them with a copious amount of shredded scallions and ginger and douse with a few tablespoons of rice wine. Steam for one hour.

I initially encountered the marinate-steam-deep-fry cooking technique in the recipe for Crispy, Fragrant Duck (xiangsu ya) in Mrs. Chiang’s Szechwan Cookbook. Mrs. Chiang prescribes at least 24 hours of prep time to successfully execute this dish. The first time I made xiangsu ya, I started out by drilling a pair of holes into a ceiling beam over my kitchen sink. I needed to install hooks from which I would suspend my rendering ducks. I can distinctly remember standing on a rickety step-ladder with a power drill in hand thinking: this Sichuan infatuation of mine is getting serious.

I later discovered in Robert Delf’s The Good Food of Sichuan a recipe for fried chicken drumsticks that distilled the basic xiangsu ya process down to about four hours. I tested this out at a legendary 30th birthday party for a close friend in 2002. The reception was enthusiastic but a surprising number of leftovers remained post-party, leading to me to conclude that drumsticks were too bulky to work as ideal finger food.

So I adapted the recipe for chicken wings. Looking back, this (slight) innovation constituted a landmark moment in my life, the end of an epoch and dawn of a new era. Before: I was a technology reporter with a passion for Sichuan food. After: I was a party-thrower who incited community glee and solidarity via fried chicken wings.

The secret was the steaming. Pre-cooking the wings not only renders the flesh into melt-in-your-mouth tenderness but also reduces the time required for deep-frying to a minimum. The ensuing juxtaposition of crispy exterior with succulent interior offered a demonstration of complementing yin-yang contrasts.

After my first bite of a Szechwan chicken wing, I knew there could be no other wings. I found an unexpected peace in this revelation. My striving days were over. I had ascended into the azure chicken wing heavens. My arc was complete.

I started living my life so as to maximize opportunities to proselytize my wings. When the San Francisco Giants reached the World Series and the 49ers made the Super Bowl I was ready. I convinced my children to request wings as birthday party accouterments. Have steamer, will travel: I made wings at Lake Tahoe and the Russian River and in Gainesville, Florida. I strapped a wok to the back of my touring bike with bungee cords and rode from Berkeley down to Montara. I made them for my father, the man who bequeathed me with a savage thirst for the salty and savory, just once, a few weeks before he died.

But the true apotheosis of my love affair with Szechwan chicken wings only arrived after the Golden State Warriors emerged from decades in the basketball wasteland and established themselves as one of greatest teams in the history of the sport. There was just something about the way this team played -- the way excellence was infused with joy and unscripted creativity, the way Draymond and Klay and Steph and Iggy anticipated and facilitated each other’s transcendence -- that cried out for collective celebration. People, I decided, are fundamentally happier when they can gasp in common, in a shared physical space, at a Game Six Klay Thompson three pointer. I started to see my role in life as the facilitator of that happiness. Perfection on the basketball court demanded perfection from the chicken wings.

What did this all mean? How did it connect with my larger project of interpreting the world through Sichuan food and Daoist philosophy?

In November 2015, with the Warriors already well on their way to a record-setting 73-9 season, I started to sense a great convergence. I sent an email to an editor at the New Yorker:

... I think I have come across some pretty intriguing stuff in the teachings of Laozi and Zhuangzi (Chuang T'su) that goes a long way towards explaining the near-perfection that is Warriors basketball. Basically, the Warriors well-known strategy of "never running a set play" is a form of enlightenment that the Taoists would have recognized instantly and have long been recommending.... Zhuangzi did not believe in rules, or prescriptions. He believed that the right course of action is come to spontaneously by embracing your current moment. This is exactly how the Warriors play. Their every movement is determined by what the opposing team is doing -- all five Warriors "read and react" and spontaneously do the right thing. They find the spaces in the joints. They make it look so goddamn easy. It's not just a gorgeous thing to watch -- it's a gorgeous, fulfilling _way to live_.

The pitch, sadly, was rejected. But no matter. I had found my path.

END OF PART I. READ PART II.

Andrew, wanted you to know that this post has inspired Elizabeth to attempt The Wings to celebrate Klay Day. We’ll be hoisting a cocktail in your honor from Kilauea.