The Road to Shu is Hard

The road to Shu is hard.

Harder than climbing the sky.

On a Cathay Pacific flight from Hong Kong to Chengdu, in April 2019, a few weeks into the beginning of the Year of the Pig, I am reading a passage in "Looking for Chengdu," a diary kept by the feminist Marxist anthropologist Hill Gates. She is recounting her anxiety upon arriving in Sichuan for the first time in 1987. Her mastery of the local dialect is poor, her research connections paper-thin, and Sichuan itself has only just begun to open up to Westerners after decades of isolation. But Gates bolsters her resolve by reflecting on the experiences of another woman who made her way to Sichuan when travel to southwestern China was exponentially more challenging.

"The famous Victorian traveler, Isabella Bird Bishop, did it in 1896 with no Chinese and a broken heart; I can, too."

I take a moment to appreciate the resonance. On my own way to Sichuan for the very first time, on the cusp of finishing a journey that started, depending on how you reckon it, three, or maybe twenty, or possibly even thirty-five years ago, I am contemplating the anxiety of an American visitor to Sichuan thirty years earlier who sees echoes of her own travails in a journey made by a British woman another century earlier. And so it goes: I look into this hall of mirrors and see myself at the end.

The pure logistics of my travel, compared to Bishop or Gates, have been easy. A jet from San Francisco to Hong Kong, a short layover, a second flight to Chengdu. Upon arriving I will, with only a few minor hitches, catch a subway ride from the airport to a five-minute walk to my AirBnB, where I will set up my VPN and post to Facebook via wi-fi within about twenty minutes of getting into the apartment. But as my flight makes its final descent, I am gripped with my own stomach-clenching fears.

I've been preparing for this trip for years, spending hours every night regaining long-lost Chinese fluency, ransacking the archives of UC Berkeley's libraries for books and articles on the history and culture and economics of Sichuan. I can talk your ear off about how peasant-pioneered agricultural reform in the 1970s in Sichuan kicked off the great Chinese economic boom that has rocked the entire world or how third century B.C. irrigation infrastructure in the Chengdu plain gave birth to the province's millennia-strong nickname "the land of plenty," while offering the modern world potent lessons for resiliency and sustainability. I have deep thoughts on soybeans and pig feed and global trade that connect Trump to Watergate and the Brazilian cerrado to Japanese tofu that I am all too ready to share with residents of the region on earth that produces and consumes the most pork in the world.

I am trying to write a book about how Sichuan food explains the world, and the moment of truth, the 火候 (huohou), for whether this project will ever become real, is nigh. The closer my plane inches to Chengdu the more my adrenaline surges. Because I am terrified.

What if I don't like Chengdu? What if my Chinese isn't good enough? What if my dream, to turn my obsession with Sichuan cuisine into a narrative vehicle about globalization and interconnectedness, is just another privileged oriental fantasy? Why in the world, at age 57, have I decided that this is what I want to do with my life?

The Road to Shu is Hard. So wrote Li Bai, the great eighth century Chinese poet, lover of wine and women and the moon, expert swordsman, Daoist adept, a man endlessly passionate in his embrace of all things. Li Bai was raised in Sichuan -- or, as it was then called, Shu. Generations of Chinese poetry scholars have argued about whether the poem is an allusion to his own difficulty obtaining a post in the government civil service, or a metaphor for the challenge of obtaining anything that one really wants, or a convoluted reference to the tangled politics of his time, but we don't need to resolve any of that here. All that's necessary is to thrill to the sheer exhilaration, the roller coaster exuberance, of his words describing the phenomenal physical challenges of getting into Sichuan. (Translation by Lucas Klein.)

The Road to Shu is harder than climbing the sky.Hear this and your face bleaches out.

These linked peaks are a foot from the sky.

Decrepit pines hang upside-down from the cliff face.

Flying and bursting, waterfalls cascade with whooshes and whirs.

Thundering gullies spin stones and bang walls.

How dangerous this is. You: Long-road Traveler:

Why in hell are you coming this way?It's a good question. For millennia, one of the defining characteristics of Shu was its inaccessibility. To the west loomed the Tibetan massif. To the north and east, the Daba mountain range cut off passage to the classical Chinese heartland. In the south: yet another mountain range and the Yangzi, China's "Great River." You needed to be motivated to get to Shu.

Which is not to say that there weren't ample perks for those who made the passage. With inaccessibility came relative safety. Sichuan is a well-watered, fertile and temperate land where just about everything a human could want to eat flourishes. Within China, Sichuan has been a lodestar for internal mass immigration for many centuries, a promised land for peasants fleeing agricultural failure, natural disasters, and war. The same geographical features that posed such great obstacles to travel were also militarily advantageous. The Tang Dynasty Emperor Xuanzong fled to Sichuan when his top general An Lushang, rose up in revolt. Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek moved his Nationalist government to Sichuan in response to the Japanese invasion in the 1930s. By one account, over the last 2000 years there were at least seven distinct instances in which an independent political entity ruled Sichuan -- a pattern that gave rise to a common saying that Sichuanese take a feisty pride in repeating today: Sichuan is always the first to break free of imperial rule, and the last to be re-conquered.

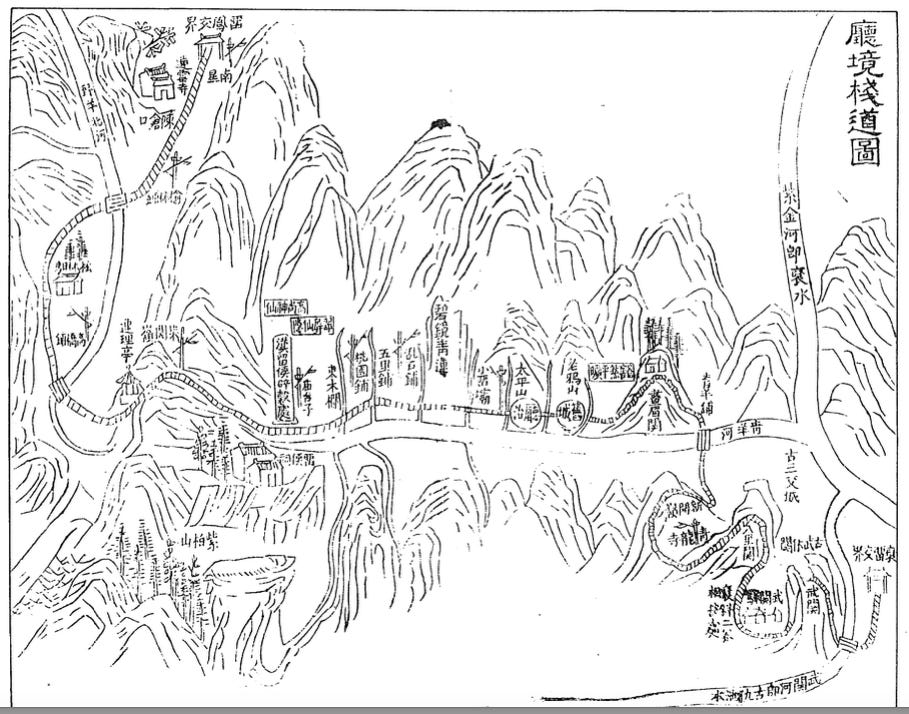

(Emperor Xuanzong's Flight to Shu, Southern Song Dynasty)

Emperor, general, peasant. Their reasons for daring the perilous passage to Shu made sense. Did mine?

I experienced my first amazing Sichuan meal as a 22-year-old Chinese language student on my first day in Taipei, Taiwan in the fall of 1984. For the last 20 years, while working primarily as a technology reporter who occasionally dabbled in politics and economics coverage, I've been regularly cooking Sichuan cuisine for myself, friends, and family. Three years ago, I fell in love with the idea of exploiting my Sichuan fixation to explore a larger universe. Soybeans and Sichuan pepper, mapo doufu and gongbao jiding -- every dish, every ingredient, every cook is an entranceway into multiply intersecting narratives of globalization rooted in history and pointing towards the future.

How Sichuan food explains the world.

But despite having made numerous trips to China over the decades, I had never once set foot in Sichuan. And despite avid interest from agents, my first version of a book proposal was rebuffed by publishers. And despite spending the last three years relearning how to speak and read Chinese, I have discovered that the journalism market would much rather pay me to write about the blockchain or the latest online erectile dysfunction startup than anything having to do with ancient Chinese history, the soybean industry, alcoholic Sichuanese poets or Daoist enlightenment. Not to mention the always nagging question: as a white man fascinated with China, I follow in the steps of a long line of imperialists, colonizers, expropriators and missionaries. How did the story I was trying to tell complicate that narrative? What did I have to add to the Sichuan spice mix?

The road to Shu is hard but not insuperably so. In the aftermath of the fall of the Ming Dynasty in the 17th century and a combination of natural disasters, war, and deranged massacres that depopulated Sichuan by an estimated 80 percent, the new Qing Dynasty encouraged mass migration to the region. By the nineteenth century, Chengdu was a city of immigrants where everyone came from somewhere else.

As I have learned more about the evolution of Sichuan food as we know it today, I have become increasingly fascinated by the theory that the complexity of Sichuan cuisine is a function of precisely this immigrant diversity. The story of how peasants from Hunan brought the chili pepper to Sichuan is reasonably well known. But according to a newspaper article published by the food writer Tejiazhedui in Hong Kong in the 1950s, peasants from all over China brought their own regional specialties with them to Sichuan, their own cooking techniques and flavor combinations. In Sichuan, it all got mixed up together.

Sichuan cuisine delights in throwing flavor on top of flavor, of mixing and matching multiple taste sensations and cooking strategies. So one can argue that what gets lauded as "authentic" Sichuan food in the 21st century is fundamentally an exercise in mix-and-match hybrid fusion that has been bubbling over for centuries.

As a citizen of the United States at time when my government is doing everything it can to demonize immigration and reject hybridity in all its forms, and as an inhabitant of a planet in which the two greatest powers, China and the U.S., seem to be accelerating into a tailspin of dire confrontation, it has occurred to me that telling stories about how promiscuous border-crossing and cross-fertilizing experimentation are a source of incredibly great culinary pleasure and cultural strength is more than just a quixotic obsession. I have come to see it as a mission, as absolutely mandatory. I am convinced we need more connection, more translation, more ingredients swirling in the hotpot, and more feasting together around a common table, with the wine and conversation and poetry flowing.

Li Bai was raised in Sichuan. He, along with his contemporary Du Fu, who also spent a significant portion of his life in Sichuan, are generally considered to be the two greatest poets in the entire classical Chinese pantheon. But Li Bai wasn't born in Sichuan. He was, in fact, an immigrant. Historians believe his mother was of Turkish extraction and his birthplace somewhere in central Asia.

When I first learned that Li Bai, a poet who to this day enjoys the honor of having his words memorized and recited by millions of Chinese children, wasn't actually born in Sichuan, I was a little disappointed. It seems ludicrous to write these words now, but I felt that it somehow weakened my case for making Sichuan out to be an extraordinary, exceptional place worthy of a crazy ass book. But now I've come full circle. I am delighted that Li Bai was an immigrant to Sichuan. Because who better than an immigrant to know that the road to Shu -- the road to anywhere worth going, or anything worth doing -- is hard?

With Li Bai and Zhuangzi as my muses, with my larder stocked with Sichuan pepper and fermented fava bean paste and my own home-made chili oil, with the help of so many historians and anthropologists and poets and writers and travelers who have gone before me seeking meaning out of history's constant mayhem, I am now, more than ever, on the road to Shu, and more than ever convinced that the stories I want to tell are meaningful in this ominous age of Trump and Xi Jinping, of Hong Kong protests and soybean tariffs, of rising ethno-nationalism and polarization on all fronts. I hope you'll join me.

that's the most interesting translation of Hard Roads to Shu I've read in a long time! the link to the whole poem reveals a great translation that Li Bai would have been proud of! As to whether it was meant as a metaphor of politics, government jobs, or the meaning of life and everything; the roads to Shu WERE hard! especially in Li Bai's time. travelling over plank roads chiselled into cliff faces mustn't have been that easy. Happy talk in Brocade City indeed!