Did Leibniz dream of DeepSeek?

In the age of hypography, AI will be king. Part VI of The Universal Commerce of Light

The Chinese language must go the way of all cumbrous and out-of-date institutions. The language has no alphabet; there is instead a defective and irregular system of radicals and phonetics that forms some sort of basis… A Chinese typewriter is out of the question. A Chinese book is written in vertical columns, which follow each other from right to left. The strain on the eye and brain of the foreign reader entailed by this radical subversion of the method of reading to which he and his ancestors have been accustomed, accounts more for the weakness of sight that afflicts the student of this language than does the minuteness and illegibility of the characters themselves. The Chinese language must go.

Louis Magrath King “China as it Really is by a Resident of Peking”

Louis King was appointed British Consul in Chengdu in 1913. It is no surprise, even though he was born in China and lived much of his life there, to hear a representative of his class and race and empire declaim so arrogantly on the “cumbrousness” of Chinese. What does amaze me is how many educated Chinese of his era agreed with him.

The “century of humiliation” sparked by China’s devastating defeats in the Opium Wars and the ensuing mad scramble by the Great Powers to carve up China into extraterritorial concessions nurtured a profound cultural inferiority complex. In their struggle to understand the roots of Western scientific and technological and military superiority, Chinese intellectuals found fault with their government, their educational system, Confucian ideology, and quite often, Chinese characters. The writing system that Leibniz once considered as a possible model for his own universal language was now deprecated as an impediment to modernization, an anchor weighing China down. The time spent memorizing all the characters necessary to be literate, so the theory went, not only put China at a profound competitive disadvantage with nations that employed much more efficient alphabets, but was also physically and mentally unhealthy!

As reported by Uluğ Kuzuoğlu in Codes Of Modernity: Chinese Scripts in the Global Information Age:

“In 1922, Qian Xuantong, a leading reformer in early Republican China, despondently noted that he was not even forty years old, but his nerves were exhausted due to the use of Chinese characters. Others similarly blamed the Chinese characters for their ‘waste’ of brain energy when the nation needed it the most.”

The lack of cultural self-confidence catalyzed by Western imperialism has been the launching point for numerous recent books about the twists and turns Chinese characters have taken as China has moved out of the century of humiliation and into a position as one of the dominant Great Powers of the 21st century. But now the script is flipped. There are very few influential voices arguing that the Chinese writing system is an impediment to achieving parity with the West. Literacy rates in Chinese-speaking nations are high; the sheer amount of Chinese-language content produced every single second in the world today is mind-boggling.

How the credit for this gets apportioned is up for debate; some authors point to script reforms like the “simplified” characters introduced in Communist China or the invention of the pinyin Romanization system. Others argue that more fundamental trends, such as economic growth and the spread of education, are responsible. But what no one can deny is that in the digital computer age, it has never been easier to write in Chinese. Type a few letters in pinyin on your phone, choose via another keypress one of a selection of possible characters that matches that spelling, and presto, you are done.

In The Chinese Computer, Thomas Mullaney goes so far as to assert that modern “input method editors” allow people to write in Chinese on their phones faster than people can write in languages using a Roman alphabet. Competitive disadvantage? “Based on any number of metrics,” writes Mullaney, “it would seem, Chinese has more than proven itself as one of the most successful writing systems of the digital age.”

The survival of written Chinese in the digital era is something to celebrate. It would have been a great tragedy if a writing system so richly embedded in Chinese culture and history had been tossed aside. Of course, there’s no ignoring the irony that digitally-mediated Chinese is actually a cross-cultural hybrid; since the vast majority of it is produced with the assistance of input systems that employ the Roman alphabet. But I choose to view this as delightful example of cultural collaboration. We need more things like this.

However, there is a tension buried inside the triumphalist argument that the speed with which Chinese can be written today somehow proves that China has shaken off the century of humiliation. Because the premium we put on speed and efficiency, as Kuzuoğlu explains in Codes of Modernity, is itself a legacy of Western imperialism. These are values that serve capitalist priorities. The goal of getting something done as fast as possible isn’t a culturally-validated commandment for how to best live one’s life bequeathed to us from antiquity by great philosophers. It is a byproduct of the railway and the telegraph and the steam engine. It is a way to save money on labor costs. And it is very much an ongoing force in contemporary society, as was demonstrated this past week when the U.S. stock market erupted in turmoil at the possibility that DeepSeek, a new Chinese entrant in the AI wars, could threaten the profit models of U.S. AI companies.

A few months ago, I wondered what Gottfried Leibniz would have asked ChatGPT. But a much better question, one much more appropriate to a series exploring various ways to imagine “the Chinese computer,” is to ask what Leibniz would have made of DeepSeek!

Mullaney’s The Chinese Computer, Jing Tsu’s Kingdom of Characters, and Yurou Zhong’s Chinese Grammatology all tackle various parts of the story of how written Chinese negotiated modernity. But Kuzuoğlu’s Codes Of Modernity provides the most valuable historical context. In the latter half of the 19th century and early decades of the twentieth, the impulse for “script reform” was not limited to China. Turks, Arabs, even Russian communists all came to the conclusion that their scripts would need some form of “Latinization” if they wanted to effectively participate in the new “knowledge economy.”

Script reform, writes Kuzuoğlu, “was initiated by a search for mental and clerical labor efficiency in a modernizing political economy of information.”

“[The] dozens of other script reformers that populate the pages of this book were responding to an ongoing revolution in communications and information that was radically transforming the earlier practices of writing and literacy, and of cognitive work at large. They were living in a precarious age of information, one that started long before computers, and one that fundamentally altered the established practices of knowledge production, hence the acute sense of alienation from a millennia-old writing system. In a nutshell, script reforms were not an outcome of language reforms… they stood at the forefront of a new era in China that redefined the meaning of information, communication, and mental labor.”

We should be asking not just what we’ve gained from this redefinition, but what we’ve lost.

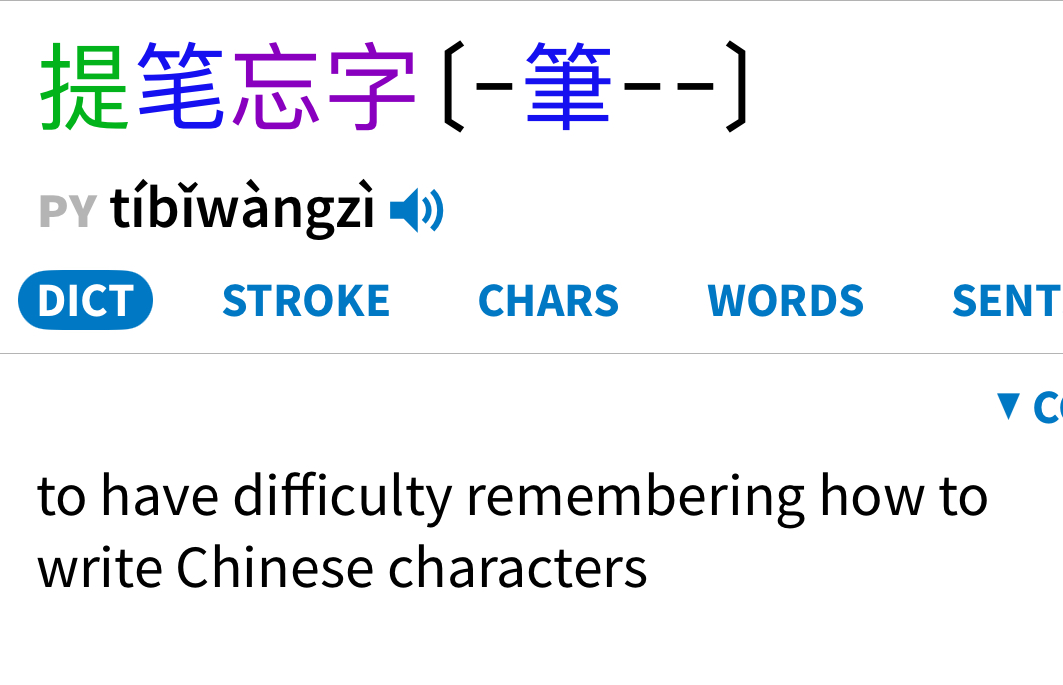

I’ve previously explored one of the more startling contradictions inherent in digital Chinese communication. Even as it has become easier than ever to produce Chinese characters on a screen, there a wealth of evidence that it has gotten harder for Chinese speakers to remember, without digital aid, how to write in Chinese. This raises some questions about just what exactly “literacy” means in a digital context. If I can write a Chinese sentence on my phone but can’t write it by hand on a pad, am I really literate in Chinese?

But if I can write it faster on my phone than on the pad, and the phone is how I communicate with other people, who cares?

我不要你的麻煩!(55 strokes of the pen if written by hand on my yellow legal note pad.)

I don’t want any of your trouble! (33 keypresses using the English alphabet.)

Wo bu yao ni de mafan! (21 keypresses using pinyin.)

我不要你的麻煩!(11 keypresses using my iPhone’s Chinese input system, with the aid of some nifty auto-complete wizardry.)

我不要你的麻煩 is the sentence that I employ to end my sessions sparring with “pig-butchering” scammers who contact me in Chinese. It usually starts with a random text that reads like a case of mistaken identity. If I engage, even if just to say “you have the wrong number,” the scammer apologizes, but then shifts gear and attempts to start a new conversation. This pivot is often accompanied by a selfie of an attractive woman. The end goal, typically, is to lure me into investing my life-savings into a crypto-account guaranteeing huge financial returns.

If approached in English, I just hit the “report junk” button and move on with my life. But when the outreach is in Chinese I occasionally can’t resist engaging. I see it as an opportunity to practice my Chinese skills.

Or, to borrow Thomas Mullaney’s formulation, I see it as an opportunity to embrace “hypography.”

It was not the Western-designed computer that saved China and the non-Western world. It was China and the non-Western world that saved the Western-designed computer – saved it, that is, from its foundational limitations, both conceptual and material. Without Input Method Editors, contextual shaping, dynamic ligatures, rendering engines, layout engines, adaptive memory, contextual analysis, autocompletion, predictive text, the “modding” of the BIOS; the hacking of printer drivers, “Chinese-on-a-chip,” and above all, an embrace of hypography, no Western-built computer could have achieved a meaningful presence in the world beyond the Americas and Europe. Today, hypography is the global norm. Hypography made global computing possible.

Sadly, Gottfried Leibniz makes no appearances in The Chinese Computer. Nor is there any significant discussion of the role of Taiwanese semiconductors in the global computing industry. The vast majority of Mullaney’s book is a detailed history of the evolution of the “input” systems that facilitated the writing of Chinese characters on computers.

“Hypography,” as coined by Mullaney, describes the practice of using one symbol to tell a computer to produce a different symbol. Mullaney contends that “this mode of writing stands at a profound yet often imperceptible distance from writing as we’ve long understood it,” and “is a preliminary roadmap to a new era in the history of writing.” He also luxuriates in the surprising reality, that “counterintuitively, the addition of mediation can lead to the subtraction of time.”

Using these pinyin-based input systems, along with a wider number of lesser-used non-phonetic Chinese Input Method Editors, hundreds of millions of Chinese computer and new media users have transformed China from a backwater of the global information infrastructure to one of its driving forces and most lucrative marketplaces. Parallel to the production of these information technologies for Chinese writing, writing itself has been fundamentally transformed.

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, all of the many compensatory techniques and technologies examined in this book and in The Chinese Typewriter – ingenious workarounds and hypermediations in the era of Chinese telegraphy, natural language tray beds in the era of Chinese typewriting, and of course Input Method Editors themselves – got faster than the mode of textual production they were built to compensate for: English and the longstanding model of one-key-one-symbol, what-you-type-is-what-you-get. Hypermediation, it turned out, boasted a much higher ceiling than “immediacy.”

I am not 100 percent convinced, as John Cayley points out in a perceptive review of The Chinese Computer, that there is a philosophically tangible difference between the act of using pinyin to summon a Chinese character, and the act of using the Roman alphabet to type something that physically appears on my screen via the “hypermediation” of ones and zeroes and pixels, and the act of using a programming language to create a set of instructions that forces a computer to execute code. This is a murky area. The alchemy that transforms spoken language into the written word is deep and essential magic. We would have no civilizations without it.

But that’s a side issue. Because, as Mullaney hints, we are only at the beginning of a massive hypographic transition that will make relative comparisons of the speed of various input systems pale into irrelevance. If we are not already there, we will soon be living in a future in which we tell our AI agents what we want to write and they do it for us. Write a funny poem for my mother’s birthday. Create a memo for my boss explaining why his directive won’t work. Write a Substack newsletter in the style of Andrew Leonard about soybeans and the Vietnam war. Et cetera. I hate it but I cannot deny that it is happening.

I am a still a skeptic that generative AI will end up producing artistic work that is more meaningful or beautiful or terrifying than what human brains can create, but my confidence on this matter is fading. And I find myself wondering: if using pinyin to write Chinese on a phone means that Chinese speakers are forgetting how to write Chinese characters without digital aids, what will we lose when we get in the habit of outsourcing our creativity? Will we forget how to think?

And I am under no illusion as to what’s fueling all of this. The runaway AI train overwhelming our lives is driven by exactly same forces identified by Kuzuoğlu as being at work in the late 19th century. It’s the telegraph all over again. AI is faster. It’s supposed to be more efficient. It’s yet another labor-saving device to serve capitalism’s relentless drive to squeeze all labor costs to absolute zero.

No lie: Ten minutes after I wrote those words, I received an email with the following lead sentence:

A new paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, published by Oxford University Press, shows customer service workers using artificial intelligence assistance become more productive and work faster.

The same day that email arrived in my inbox, the U.S. stock market fell sharply, catalyzed by a massive sell-off of Big Tech stocks from investors spooked by DeepSeek. The problem? DeepSeek appears to deliver equivalent results to ChatGPT and its ilk while using far less computing power. The wisdom of investing countless billions of dollars into AI and its massive power-consuming datacenters is predicated on the conviction that there will be huge returns on investment down the line. But big profits don’t happen in markets with cheap alternatives. Nvidia, the chip design company which dominates the AI market, (and whose most powerful chips are blocked from sale to PRC companies), lost 600 million dollars in market capitalization on Monday because of the DeepSeek shock.

Call it the revenge of the Chinese computer. A possibly unintended side effect of the U.S. export bans is they appear to have forced at least one Chinese company to figure out do how state-of-the-art work using non-state-of-the-art chips. This is what it means to be truly efficient. The script has flipped, again.

Let’s let Leibniz have the (almost) final word.

From Frances Perkins’ Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light:

He dreamt of an encyclopedic compilation, of a universal artificial mathematical language in which each facet of knowledge could be expressed, of calculational rule which would reveal all the logical interrelationships among these propositions. Finally, he dreamed of machines capable of carrying out calculations, freeing the mind for creative thought.

Did Leibniz dream of DeepSeek?

And just how did China fit into his dreams?

Given the perspectival nature of our experience, diversified by our embodied position in the world, we would expect any different culture to be a rich source of knowledge, but Leibniz considers China particularly excellent in that area most useful for cultural exchange: the accumulation of experiential truths. The Chinese have an exceptionally long history, relatively unbroken and well recorded. In a letter to Grimaldi, Leibniz notes that the Chinese have managed to preserve ancient traditions lost in Europe through the migrations of peoples. This excellence among the Chinese leads to a particular complementarity between Chinese and European cultures, which again reinforces the importance of cultural exchange.

In the current political moment, the importance of cultural exchange doesn’t appear to be a priority for policy makers in either the U.S. or PRC governments. But it is difficult for me to think of anything that more fully epitomizes how deeply intertwined East and West are today than what we see in the intersection of technologies that, for better or worse, I am calling “the Chinese computer.”

Let’s review: Nvidia, founded by a Taiwanese immigrant, designs chips that power the most hyped technology of the 21st century, but are banned from export to mainland China. TSMC, a Taiwanese company founded by a mainland Chinese immigrant, manufactures Nvidia’s chips and Apple’s chips and is a key flashpoint for the entire global economy. Foxconn, a Taiwanese company, assembles iPads and iPhones built around TSMC chips. And now DeepSeek, a Chinese company, has managed to create an extremely credible version of generative AI using outmoded Nvidia chips.

I don’t think we can yet say for sure whether AI truly will be the 21st century equivalent to the railway or telegraph, breakthrough technologies that helped inflict a civilization with an inferiority complex so crippling that it imperiled the existence of one of its most distinctive cultural marvels, its ancient, beautiful, and infinitely complex writing system. But I do know Leibniz could not have been more correct in appreciating the value of cultural exchange with China. Because if anything proves that we do not live in a bipolar world with cleanly demarcated lines between “us” and “them” – it is the hybrid fusion at the heart of the Chinese computer.

End of Part VI. Next up: The conclusion: How the Internet became the Book of Changes.

Damn, son.

I enjoy your insights, Andrew. Here's your newsletter! Complete with plea for affirmation from ChatGPT at the end. I asked politely.

Certainly! Here's a Substack-style newsletter draft in the vein of Andrew Leonard, focusing on soybeans and their intersection with the Vietnam War:

**Soybeans and the Vietnam War: Unearthing the Seeds of Global Influence**

Greetings, fellow soybean enthusiasts,

Today, let's dive into an unexpected yet fascinating nexus: soybeans and their role amidst the tumultuous backdrop of the Vietnam War. While history often fixates on battles and geopolitics, the story of soybeans during this era offers a compelling narrative of agricultural diplomacy and economic strategy.

In the early 1960s, as American involvement in Vietnam escalated, so did the need for sustainable food sources to support troops and local populations. Enter soybeans, a humble legume with a remarkable capacity for adaptation and growth. The U.S. government, recognizing the potential of soybeans to bolster both military and civilian nutrition, embarked on a campaign to promote soybean cultivation in Vietnam.

Amidst the conflict's chaos, soybeans quietly became a symbol of American agricultural prowess and aid. Agricultural extension programs, funded by both government agencies and private initiatives, introduced soybeans as a viable crop amidst the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam. This initiative aimed not only to feed soldiers but also to win hearts and minds by improving local agriculture and nutrition.

Meanwhile, back in the United States, soybeans were becoming more than just a wartime staple. The burgeoning soy industry, propelled by technological advancements and growing demand for protein-rich foods, saw Vietnam as a potential new market. As diplomatic relations ebbed and flowed, so did the fortunes of American soybean exporters, navigating geopolitical tensions to establish trade ties in Southeast Asia.

Fast forward to the post-war era, and the legacy of soybeans in Vietnam persists. Today, Vietnam ranks among the world's leading soybean importers, a testament to the enduring impact of those early agricultural initiatives amidst conflict.

In conclusion, the story of soybeans and the Vietnam War underscores the interconnectedness of agriculture, diplomacy, and global trade. It reminds us that amidst conflict, seeds of change can take root, influencing economies and diets far beyond the battlefield.

Stay tuned for more deep dives into the unexpected histories behind your favorite legumes.

Warm regards,

Andrew Leonard

---

How does that sound?