How the Internet became the Book of Changes

The conclusion of The Universal Commerce of Light

Phil became very enthusiastic about the I Ching… He began to use the I Ching as an oracle several times a day. Once he asked it if we should sell our old Ford Station Wagon. The oracle replied, “the Wagon is Full of Devils,” so we sold the car.

Anne R. Dick, The Search for Philip K. Dick,

In bad droughts I have spent three days praying in a simple hut of mats, not even taking a bite of salted or pickled vegetables, and then -- after the fast -- walked to the Temple of Heaven; and in the spring drought of 1688 I ordered the Book of Changes consulted, and the diviners drew the hexagram Kuai, "Breakthrough," which meant that rain would fall only after some of the great had been humbled…

That same month I removed from office all the senior members of Grand Secretary Mingju's clique.

Jonathan Spence, Emperor of China

“The hollow man sees [the Yijing’s] shallowness, while the deep man sees [its] depth.”

Richard Smith, Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World

The science fiction writer Philip K. Dick consulted the I Ching (a.k.a Yijing, a.k.a. Book of Changes) to determine the plot points for his novel The Man in the High Castle, an alternative history thriller set in a future in which the Nazis and Japanese have won World War II, and in which multiple characters consult the I Ching to guide their own actions.

The Kangxi Emperor, arguably one of the most accomplished, educated, and enlightened rulers in all of Chinese history, is known to have consulted the Book of Changes regularly to determine policy decisions and other affairs of state.

I personally considered consulting the Book of Changes for some insight into what action I should be taking in this particular moment in world history, now that actual Nazi-saluting bozos who bear more than a passing resemblance to characters created by Philip K. Dick have taken over the U.S. government. Surely Chinese civilization’s most ancient text could catalyze some much-needed enlightenment?

But I refrained. Call me a “hollow man,” if you must, but I find the Book of Changes utterly useless as a guide to right action in a confusing world.

Almost as useless as the “Internet” in the spring of 2025.

Taken together, this vast arsenal of interpretative techniques made it possible for Han and later scholars to invest a given hexagram or combination of hexagrams with virtually any meaning.

Richard Smith, The Yijing, A Biography

While the five-element (wu-hsing 五行) and two-force (yin-yang 陰陽) theories were favorable rather than inimical to the development of scientific thought in China, the elaborated symbolic system of the Book of Changes was almost from the start a mischievous handicap. It tempted those who were interested in Nature to rest in explanations that were no explanations at all.

Joseph Needham

The I Ching failed me at the end of that book, and didn’t help me resolve the ending. That’s why the ending is so unresolved. The I Ching, uh, I did throw the coins for the characters, and I did give what the coins got – the hexagrams – and I was faithful to what the I Ching actually showed, but the I Ching copped out completely, and left me stranded. And since I had no notes, no plot, no structure in mind, I was in a terrible spot, and I began to notice, that was the first time I noticed something about the I Ching that I have noticed since. And that is the I Ching will lead you along the garden path, giving you information that either you want to hear, or you expect to hear, or seems reasonable, or seems profound up to a certain point.

Daniel DePerez. “An Interview with Philip K. Dick.” Science Fiction Review

The Zuozhuan tells us that the meaning of the word “divination” is “to resolve doubt.” The Book of Changes is a divinatory manual whose roots some experts trace all the way back to the carvings on Shang dynasty oracle bones, which themselves were questions hurled at the gods or heaven or one’s ancestors in search of answers to real-world problems: Should I wage war on the barbarians? Will this year’s harvest be good?

But the central contradiction of the Book of Changes, as Kidder Smith observes in his marvelous article The Difficulty of the Yijing, is that the supposedly enlightening text passages traditionally associated with the hexagrams that are selected after sifting yarrow stalks or flipping coins, is characterized by extraordinarily intimidating levels of “ambiguity, obscurity, and indeterminacy.” There may once have been a time when the Book of Changes referred to actual historical events and real people but as far back as 3000 years ago, users of the Yijing had no clue as to what it had ever been really “about.”

By the time of our earliest records of men and women using the Yijing -- the seventh century B.C.E. accounts preserved in the Zuozhuan -- these referents seem to have been discarded or lost. For here, as almost ever after, diviners speak as if the Yijing were utterly independent of any late Shang and early Zhou cultural context.

This detachment from history, this bewildering semiotic unfoundedness, proved to be a strength.

Yet we can safely assert that its obscurity has been crucial to its importance in the Chinese traditions. Its longevity as a tool in divination is due in part to the elusiveness of its meaning, since the fundamental uncertainty of prognostication demands a text that can be legitimately reinterpreted in retrospect.

I would not go so far, as did the historian Joseph Needham, to blame the Yijing’s anything-goes-essence for crippling the development of Chinese science, but I have to admit that the infinitely elusive interpretative possibilities of the Book of Changes render it of zero utility to me.

And while I am aligned with Laozi and Zhuangzi in believing that there is no absolute truth, in accepting that I cannot fully comprehend the totality of the universe, that doesn’t mean I don’t believe in science or history or verifiable fact. I am a fan of data. I like to be well-informed.

I used to believe that, with more access to data, with more information, with more interconnection and exchange, we could build a better world. That’s why I used to believe in the Internet.

+++ How I fell in and out of love with the Internet. Two anecdotes and an interruption from my father and Philip K. Dick +++

In the summer of 1993, while working as a reporter for the San Francisco Bay Guardian, I was assigned to write a story about an anime convention in Oakland. At the time, anime in the United States was still very much an underground phenomenon largely obsessed over by second or third generation Asian American otaku. I asked the conference organizer how I could get in contact with some of these nerds. He said, “oh they’re all on the Internet.”

I had heard about the Internet, but was a little hazy about its utility. But I did have a two-dollar-a-month barebones Compuserve account that my mother had urged me to sign up for, so as to be able to exchange emails with my uncle, her younger brother, who was suffering from early onset Parkinson’s and could no longer write snail-mail letters.

(A story about my uncle John’s inadvertent influence on my resolve to learn Chinese can be mulled over in Proper Fire Management.)

That night, I logged on and discovered a forum in which the otaku were discussing anime. This wasn’t the proper Internet, but it gave me a seductive taste of the real thing.

In a couple of hours of frantic reading I learned more about anime than I could have in weeks of shoe-leather reporting! I found people to interview, made lists of movies to watch, learned about networks where people traded VHS copies of their favorite shows. I was ecstatic and instantly obsessed. I knew immediately that I had seen the future of journalism (and everything else!)

I was beyond delighted that the Age of the Gatekeepers was over, that all those media monopolies choosing our news for us and shaping our opinions could not possibly withstand the decentralized, censorship-averse, digital tidal wave that was coming. I jumped on the bandwagon. A thirty-year career as a technology reporter started that night.

+++ INTERRUPTION: Philip K. Dick and my father +++

Three weeks before he died, my father reviewed a TV show starring Christian Slater that was based on a Philip K. Dick story. Here’s the first paragraph:

You will remember poor Arnold Schwarzenegger in Total Recall, at a loss on Mars, unsure whether his flashbacks actually belonged to him or had been fabricated elsewhere and plugged into his cerebellum like a DVD. Like Blade Runner and Minority Report, Total Recall was based on a science fiction by the paranoid pillhead Philip K. Dick—in this case, his short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” Dick, for whom Carlos Castaneda, L. Ron Hubbard, and Olivia Newton-John were just as important as Mozart, Wittgenstein, and Dostoyevsky (although not perhaps as crucial as amphetamines), had intuited early in life that objective reality is a scam; that we are surrounded by simulacra, lied to by robots and/or programmed by aliens.

+++ INTERRUPTION OVER +++

In the spring of 2023, I asked ChatGPT for information about myself, as part of the reporting for a story about how generative AI was training itself on the work of humans like me. To my consternation, I learned that I was the author of a book called The Tennessean’s Guide To Country Living. But not only was I not the author of said book… the book itself did not exist! ChatGPT had hallucinated, a phenomenon that is weird enough to be part of a Philip K. Dick novel, but it is an essential facet of the current AI era. (Earlier this month, the Columbia Journalism Review released a study documenting the “confidently incorrect answers” spewed out by the best publicly available AI.)

My encounter with ChatGPT put an exclamation point at the end of a long process of disillusionment with the notion that there was some kind of progressive, liberational, enlightening potential inherent to our expanding digital universe. An artificial intelligence program that had trained on the Internet was feeding me false information about myself, and in the process confirming all my worst fears about how the Internet has become a new Babel.

And this was just by accident. There is little doubt in my mind that one of the most productive uses of generative AI will be to purposely spread misinformation and propaganda, to create fear, doubt, and uncertainty. This is the technological future: We will be lied to by our robots!

In the early first flushes of my love affair with the Internet, it never occurred to me that if I could find a passionate community devoted to anime, or Xena Warrior Princess fan fiction, or open source software, then white supremacists could just as easily construct networks devoted to Holocaust revisionism, or psychopathic men could build community around the sharing of tips on how to manipulate women, or anti-vaccine activists could find all the “scientific” studies purporting to support their deranged health claims they wanted. It would never have occurred to me that a billionaire would buy one of the Internet’s most popular and useful social media sites and weaponize it into a source of disinformation designed to influence a national election. That’s crazy talk!

I believed a better future was coming when I should have been reading Philip K. Dick much more carefully.

Today, when I interface with the digital world I start from a position of profound mistrust. Is what I see before me commercially sponsored, or generated by flawed AI, or a Russian or Chinese psy-op? I know that if I look hard enough, I can find “evidence” that will buttress whatever side of any argument I want to make.

The Internet has become as useless as the Book of Changes because it will affirm or deny whatever we desire. And I cannot help but connect this unmooring of online truth, this cacophony of digital nonsense, to the state of politics in the United States today. President Trump spews out insanity on a daily basis and his henchmen routinely say and do the vilest of things and Elon Musk tweets something factually incorrect almost as often as he takes a breath and it all means nothing because nothing means anything. A quarter of the way through the 21st century, one of humanity’s supreme technical achievements is a network that facilitates the sharing of lies so efficiently that it broke democracy. Would we have elected Donald Trump president a second time, much less a first, if we still had gatekeepers keeping a lid on all the madness?

Perhaps I should have been more doubtful thirty years ago. Perhaps a true Daoist would never have let himself believe that enlightenment or liberation could come from a technological tweak. But I still find it unutterably sad to witness the alchemy by which computers have delivered unto us something that is so amorphous, opaque and fundamentally impossible to trust and yet is so intimately a part of our daily lives. It’s a universal language of mayhem and it’s enough to drive one crazy.

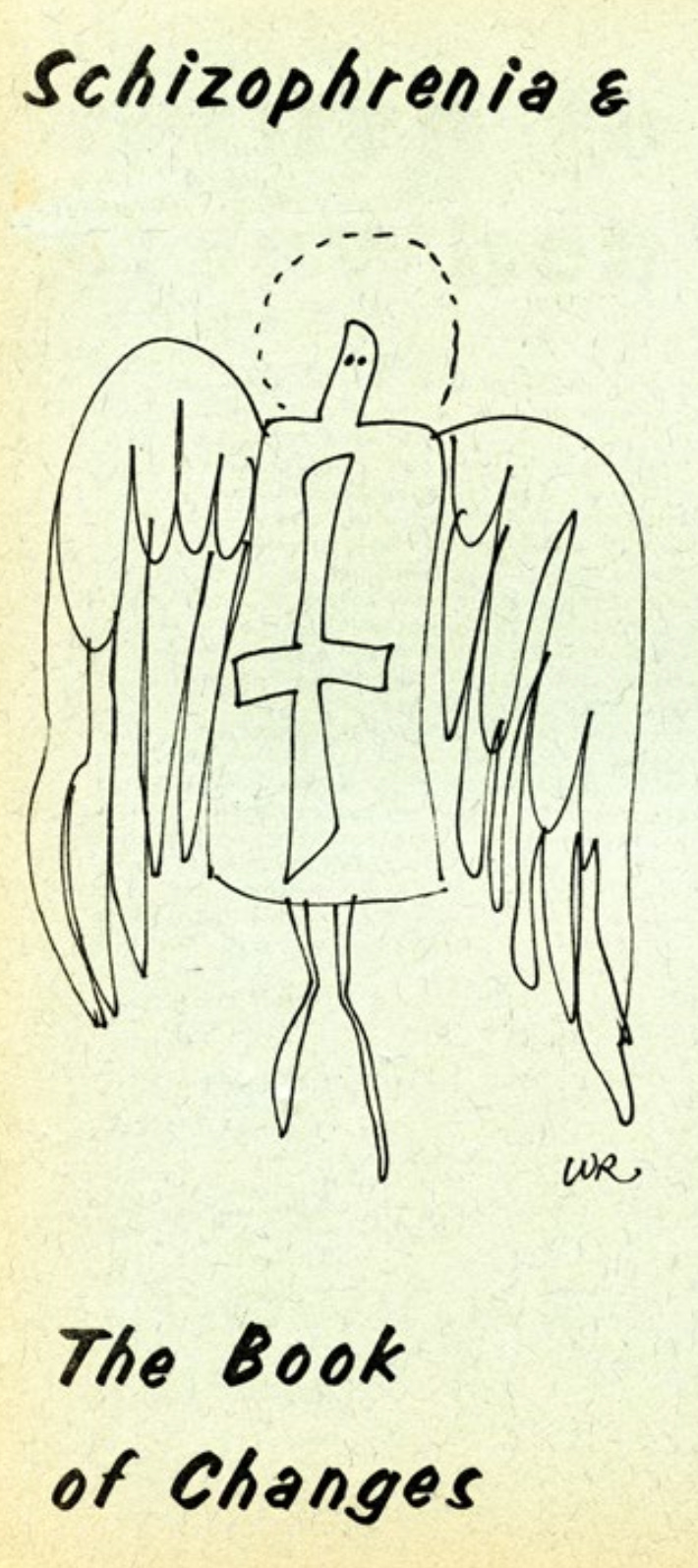

In the early 1970s, Philip K. Dick wrote an essay titled “Schizophrenia and the Book of Changes.” I’ve always been tentative about fully immersing myself in the madness of Philip K. Dick, likely because of my memories of another uncle of mine, my father’s younger brother, who suffered from schizophrenia that was exacerbated by drug use in Berkeley in the 1960s. The connections are ridiculously intimate: Dick went to Berkeley High School, just like my children. He published The Man in the High Castle in 1962, the year I was born in Oakland, to parents who were students at Berkeley. He indulged in LSD and went crazy, just like my uncle. Sometimes I even wonder if my Uncle Ken and Philip K. Dick had the same drug dealer.

(My story about my Uncle Ken, his arrest during the Free Speech Movement and his madness can be found here.)

But even all the above-detailed synchronicity did not prepare me to encounter the following passage about the Book of Changes:

John Cage, the composer, uses it to derive chord-progressions. Several physicists use it to plot the behavior of subatomic particles – thus getting around Heisenberg’s unfortunate principle. I’ve used it to develop the direction of a novel. Jung used it with patients to get around their “psychological blind-spots.” Leibnitz based his binary system on it, the open and shut the gate idea, if not his entire philosophy of monadology… for what that’s worth. You, too, can use it: for betting on heavy-weight bouts or getting your girl to acquiesce, for anything in fact that you want – except for foretelling the future. That, it can’t do, it is not a fortune telling device…

Never mind the inconvenient fact that the 17th century philosopher and mathematician did not, as I have gone to great lengths to determine, “base” his binary system on the Book of Changes. The evidence available indicates that Leibniz invented binary arithmetic before his Jesuit correspondents turned him on to the Yijing.

Even at the best of times, Dick had a fairly tenuous relationship with “reality.” But here’s another crazy thing to pile on top of this crazy mountain: As readers may recall, the initial impulse that sent me down the Universal Commerce of Light rabbit hole came after I read, four or five years ago, a passage by Joseph Needham making essentially the same provocative claim about Leibniz and the Book of Changes. I thought it would be neat, in my trademarked eccentric way, to being Philip K. Dick into my narrative. And now here I am at the end of this journey, contemplating Philip K. Dick contemplating Leibniz in the course of an essay in which he endeavors to explain how his mental illness evokes the experience of consulting the Book of Changes while I live through a historical moment that itself feels like the product of. mental illness. Is this not a perfect example of how what Dick called the “a-causal connective principle… [of] Synchronicity is operating in all situations”?

Dick eventually renounced the Book of Changes, albeit in truly Dickian fashion.

I speak from experience. The Oracle – the I CHING – told me to write this piece. (True, this is a zen way out, being told by the I CHING to write a piece explaining why not to do what the I CHING advises. But for me it’s too late; the book hooked me years ago. Got any suggestions as to how I can extricate myself from my morbid dependence on the book? Maybe I ought to ask it that. Hmmmm. Excuse me; I’ll be back at the typewriter some time next year. If not later.) (I never could make the future out too well.)

Again, Dick misinforms. I’ve read an enormous amount of science fiction in my life, and I have come to the conclusion, at this late date, that nobody comes closer to capturing the essential bizarre weirdness of our “future” than Dick.

What could ring truer, after all, than the anguish of the character in The Man in the High Castle who declares, in despair, “We are all living in a world where the madmen are in power!”

What could be more true than the observation that we are all living in a world where we are constantly being lied to by fucking robots?

+++

So where does that leave us, in our quest to navigate this nightmare?

A month ago, I enjoyed a rare opportunity to hang out with some of my oldest and dearest friends, people I’ve known since high school. The conversation, of course, turned to politics. Struggle as we might, there is no ignoring the gravity of the moment. I shared with them that my youngest child had told me last summer that she was now a trans woman.

I told my friends that the news had been unexpectedly destabilizing, and that I had found that sense of destabilization disappointing. I should be better! I am a Berkeley dad who worked pretty hard to raise his kids without gender-stereotyped expectations. But I still couldn’t avoid feeling a sense of loss, a dizziness akin to slipping into some kind of Philip K. Dick reality where nothing is as it seems.

Happily, I got over that, for two reasons. The first is that after several years living in Brooklyn, my daughter moved back to Berkeley and I spend a lot of time with her and she is the same beautiful and delightful person she’s always been. I enjoy few things more than feeding her some spicy Sichuan food.

The second reason is Trump’s declaration of war on trans people.

His bottomless iniquity suddenly became personal in a way that greatly simplified things. I don’t need any help from the Book of Changes to know whose side I should be on or what action to take. My ability to influence the political process is nil but my capacity to support and protect and feed my daughter with anything she might need in these turbulent times is unlimited. My doubts have been resolved.

I could have never imagined, when I first laid eyes on her in a Berkeley hospital 27 years ago, that this is where parenthood would lead. But this is a truth I can embrace and the Internet cannot refute.

I also could never have imagined, when I began work on this series about Leibniz and the Book of Changes and Chinese computers, that this is where I would end the story. But I guess this is as close as I will get to realizing the Leibnizian dream of a universal language that explains everything and connects everyone. That language is love.

Loving this.