Proper Fire Management

I first looked up the characters that comprise the word huohou while translating an essay about the great Sichuanese writer, Li Jieren (1891-1962). Li is most famous for his River Trilogy of novels about life in Chengdu at the beginning of the 20th century, but he was also a chef and a passionate chronicler of Sichuanese cuisine. During Sichuan's warlord era he operated a restaurant so popular -- and believed to be so profitable -- that gangsters kidnapped his son for ransom.

At first glance, Li seemed like a person clearly destined to play a role in in The Cleaver and the Butterfly. But when I learned, from the essay in Che Fu's Conversations about Sichuan Food, that as a young man studying French literature in 1920s Paris, Li regularly hosted Sichuan dinner parties for his fellow expats in his Montargis apartment, my interest turned to infatuation.

One of those expats, another Sichuanese student named Li Huang, is quoted by Che Fu as saying that Li Jieren's "widowed mother was famous among her clan for being an accomplished chef. By emulating her Jieren developed a solid foundation in everything from how to choose ingredients, knife technique, the adjustment of flavor, the proper way to handle the wok and spatula, and the mastery of heat. All of this he had practiced until he was deeply familiar."

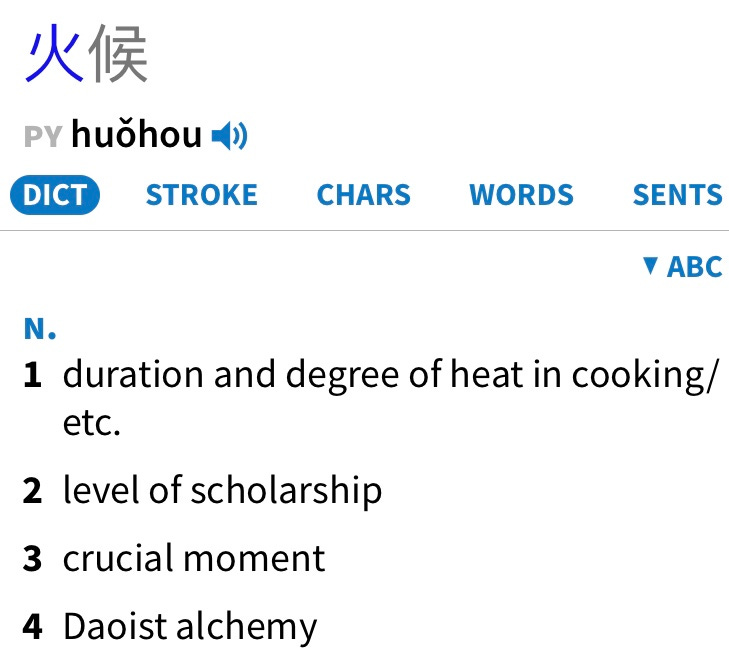

The mastery of heat! A combination of the characters for "fire," and "wait" or "duration," huohou is, according to one Chinese food historian, "the most important technique in Chinese cooking, and also the most difficult to master." The concept is particularly applicable to stir-frying, where high temperatures and short cooking times require quick thinking, agile hands, and an exquisite living-in-the-moment sensibility.

There's an engaging but elusive Daoist slipperiness to huohou. It is hard to define exactly, in, say, a recipe, how to go about exercising ideal huohou, how to recognize the "crucial moment" when the flames need to surge high or simmer low. There's a knack to it -- a sense for adjusting on the fly as the situation merits -- that develops through the alchemy of experience and intuition. The concept, as the word's multiple definitions indicate, is metaphorically potent. If your huohou is sublime, you will not only be a master chef, but you will be adept at negotiating the myriad ambiguities that challenge at every stage of life. When the moment of truth arrives, you will know what to do.

+++

I don't remember exactly how old I was when my uncle tore apart the cooking fire I was building for a family picnic. But I had to have been at least twelve, because my father wasn't there. After the divorce, summers in southern New Hampshire were no longer part of his agenda. What I do remember, as if it were yesterday, was the gut-punch of patriarchal disapproval. I remember trying to stifle tears as I stumbled away from the picnic area. I remember my grandfather attempting to comfort me.

I have built countless fires in the decades since, including at least a hundred in that very spot, overlooking a pond where my mother's family has gathered for generations. There have been bonfires in northern Florida and pig-roasts in Berkeley and the incineration of enough charcoal to reduce a dozen Webers to rubble. I fell in love warmed by the flames of one fire and mourned a broken marriage by the flicker of another.

I even set my own house on fire.

But the first fire I really remember is the one that didn't get built, the one my uncle declared "terrible." And the one that I now understand first started me on the road to Shu.

+++

I lust after Li Jieren's Sichuan dinner parties. 1920s Paris! In the Western world, the names that flocked to the city are enduringly famous: Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Josephine Baker, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Gertrude Stein. Much less well known are the thousands of young Chinese men and women who made their way to the city. Their native land wracked by warlord squabbling, their traditional worldview shattered by the devastating juxtaposition of dynastic decline and Western military and scientific supremacy, these writers, artists and revolutionaries gathered in the capital of Western culture seeking insights that would help them plot a path forward for China. They were intensely conscious of the fact that their entire civilization was facing a moment of truth.

A disproportionate number of the Chinese emigres who ended up in France came from the southwestern Chinese provincial neighbors Sichuan and Hunan. Some, like the Communist revolutionary leaders Deng Xiaoping and Zhu De, later rose to the pinnacle of power. Others ended up victims of the deadly warfare between the Communists and Nationalists, while still others scattered to Hong Kong or Taiwan. Li Jieren's life encompassed some of the most epic events of modern Chinese history -- the fall of the Qing dynasty, warlord mayhem, and revolutionary "liberation." The third novel in his River Trilogy, The Great Wave, includes a detailed account of Sichuan's "Railway Protection Movement" protest -- an uprising that many historians see as the final catalyst for the end of imperial China.

For a few years after the Communist takeover, Li Jieren even served as vice-mayor of Chengdu. But it is his dinner parties in Paris that entice me the most.

Imagine the improvisation necessary to conjure Sichuanese delights in 1920s Paris. I have so many questions. Did he even have a wok? What kind of flame did he kindle? Did the hot peppers that his friends managed to score from Andalusian migrants camped by the Seine match the potency of the chilis he'd grown up with?

As an American raised to adulthood during the peak of U.S. hegemony, the chasm that separates me from a Chinese man who was born during China's last imperial dynasty and who died during Chairman Mao's catastrophic Great Leap Forward is vast. And yet I still I feel a kinship. In a foreign land he sparked festive conviviality with fire and oil and spice. I totally get that. It's what I would do.

+++

I have no memory of what fire-building transgression inspired my uncle's wrath. In all fairness, my effort was probably feeble. Perhaps I hadn't included any kindling, and just thrown together some doomed-to-fail combination of crumpled newspaper and logs. I almost certainly hadn't allowed for the proper airflow that will breathe life into a properly-made fire. I was a city kid who spent far more time reading science fiction and watching reruns of Gilligan's Island than rubbing two sticks together in search of a spark. A Boy Scout, I was not.

The benefit of hindsight suggests that my technique might not have been the real issue. I'm pretty sure my uncle mocked my fire-making attempt and reduced my nascent structure to rubble because he felt threatened. Although highly intelligent, self-taught in both Russian and German, a hobbyist in Chinese history and a superlative maker of champagne apple cider, my Uncle John never graduated from college or held a steady job. This made him something of a disappointment to my grandfather, who, along with both of his younger brothers and their father, and their father's father, boasted degrees from Harvard and illustrious careers.

Meanwhile, my mother, who went to Radcliffe and worked all her life as a neuroscientist, was raising me to be a patriarch. My uncle must have sensed this. In a family that put great stock in ritual and tradition, my encroachment on the narrow turf where he did feel comfortable -- the making of the family picnic fire -- inevitably sparked resentment.

Back then I was as oblivious of all this context as only a teenage boy can be, even after my grandfather tried to explain to me that my uncle could be "difficult" and I was not to take his lashing out as any meaningful criticism of my ability to make a fire (or anything else). But the conversation clearly stuck. My grandfather wasn't very practiced at emotional work, but I can recall him sitting next to me looking over the surface of the pond as if it was yesterday. I can still smell the pine trees that leaned over us, see the skittering traces of waterbugs, hear the booze-fueled backdrop hum of family conversation.

And my fire-making ambitions were undeterred. I realize now that all those bonfires, all those smoked ribs, all those worn-out-Webers surely trace back to the sparks launched by that day of infamy. I was, and am, still a little pissed off.

But here's where it gets a little crazy.

I'm often asked why I decided to learn Chinese. And for decades, I have been unable to come up with a straight answer.

I have multiple answers!

Sometimes I cite random contingency. As a second-semester freshman at the University of Michigan I accidentally enrolled in a junior/senior level seminar devoted to the history of U.S. involvement in East Asia. The course was so interesting that I decided, basically on a whim, to tackle Chinese 101 as a sophomore.

Occasionally I opt for a more psychoanalytic approach. I have a theory that I turned to the Far East in order to carve out some intellectual territory not already claimed by my father and grandfather. My father read every novel worth reading and my grandfather was a scientist with a solid understanding of history who could discourse at length on practically any random subject -- provided it was part of the Western enlightenment and Judeo-Christian tradition. But on the glories of the Tang dynasty or the mysteries of oracle bones they were less sure-footed. Here was my opportunity!

If I'm feeling especially honest, I will concede that some kind of Orientalist escapism had to be involved. I buried myself in Chinese history for the same reason that I gorged on science fiction; I was hypnotized by the seductive, exotic other; the promise of a release from mundane reality.

But what I generally don't tell people is that by my second semester of Chinese I was flailing my way towards an F and was forced to drop the course. As it turns out, learning Mandarin didn't mesh well with throwing keg parties in my dorm room every Thursday night. I certainly wasn't in it for the long haul.

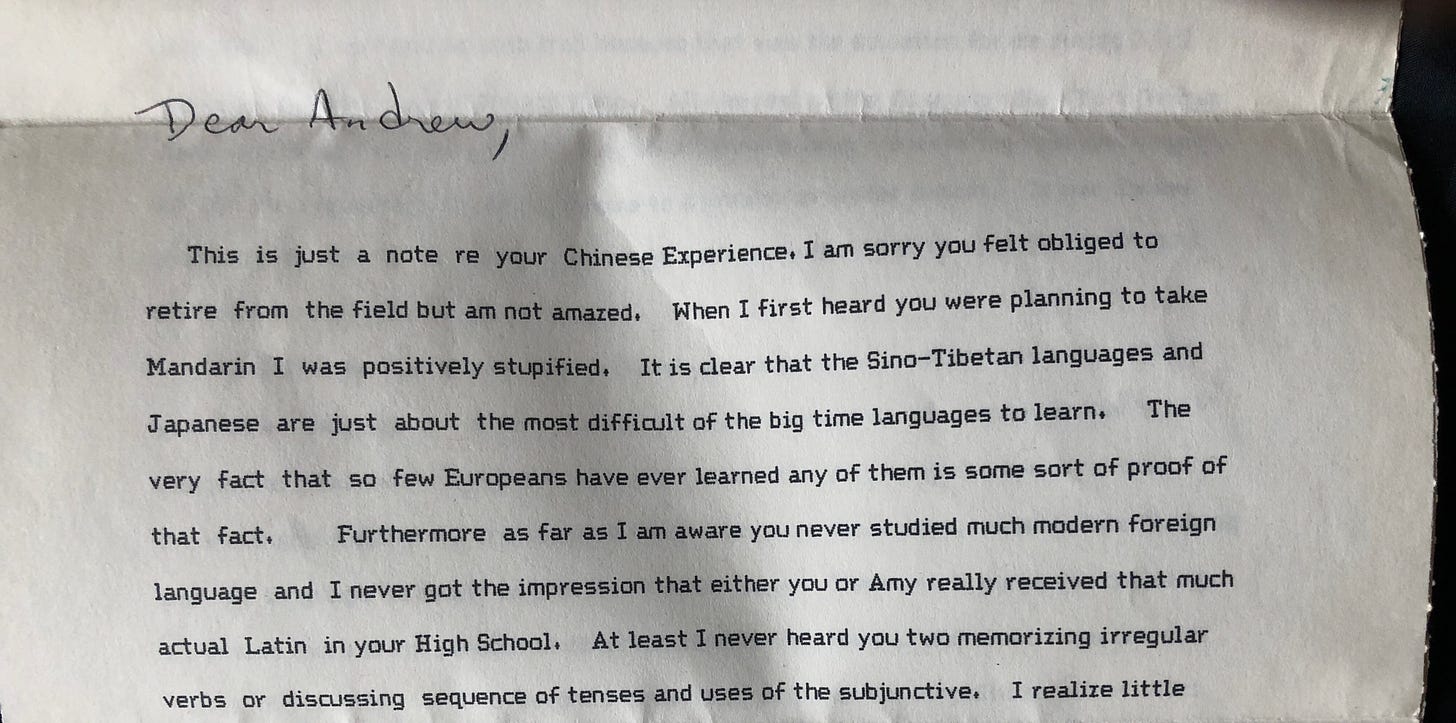

I must have written my Uncle John a letter including this shameful news because I still have his response in my possession.

This is just a note re your Chinese Experience. I am very sorry you felt obliged to retire from the field, but not amazed. When I first heard you were planning to take Mandarin I was positively stupefied. It is clear that the Sino-Tibetan languages and Japanese are just about the most difficult big-time languages to learn.... Furthermore as far as I am aware you never studied much modern foreign language and I never got the impression either you or Amy really received that much actual Latin at your high school. At least I never heard you two memorizing irregular verbs or discussing sequences of tenses and uses of the subjunctive.

I was shocked, two years ago, when I discovered this letter, because I had totally forgotten it had ever existed. But in retrospect, it suddenly seems obvious why I signed up for Chinese 101 all over again as a junior and then continued studying the language intensively for another decade. I was deeply irritated by my uncle's condescending stupefaction and wanted to prove him wrong! The same stubbornness that sent me down the path of pyromania ended up sending me to Taiwan for four years.

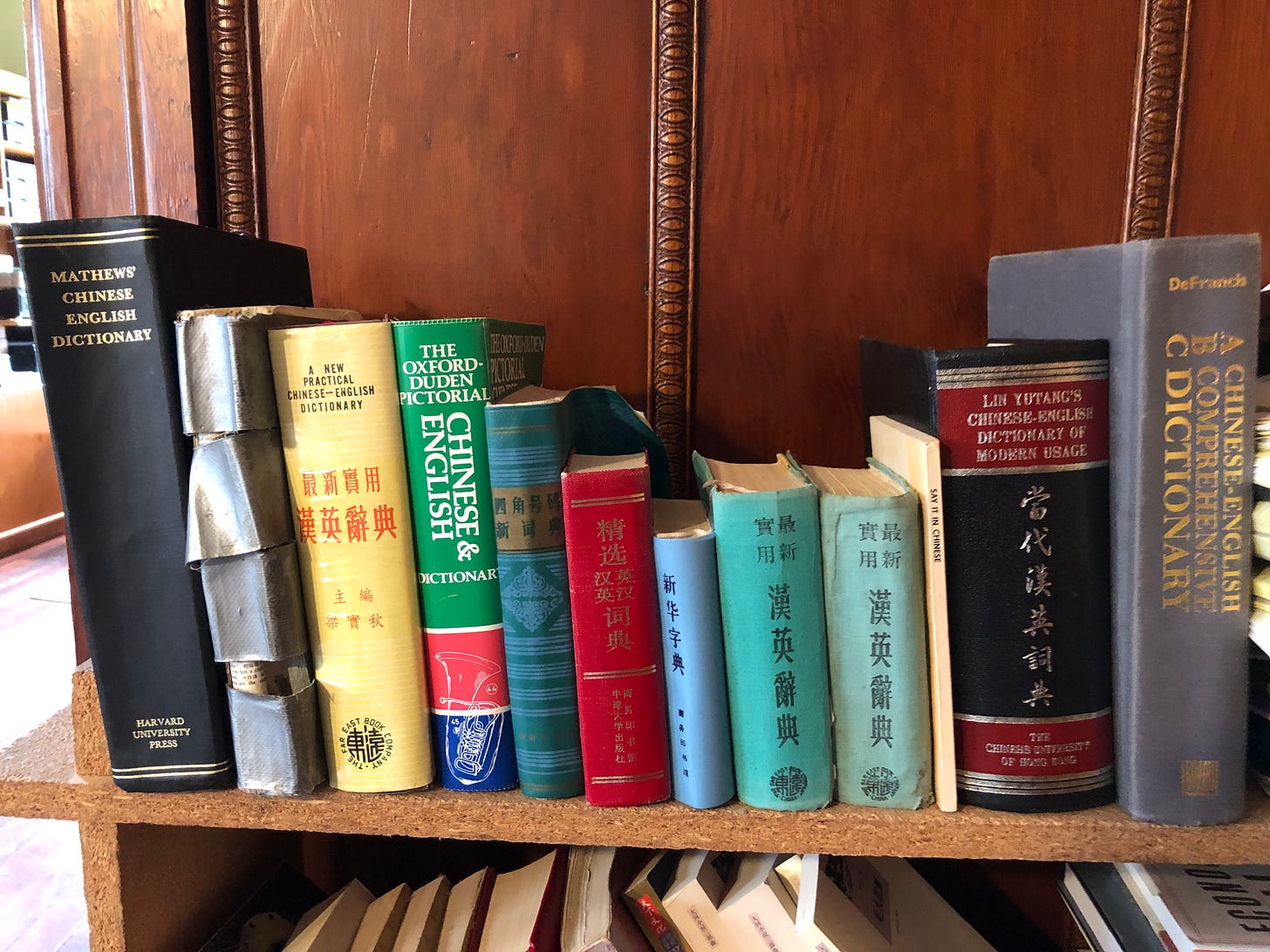

There's something pathetic about the notion that a life spent wrestling with Chinese was at least partially fueled by trying to prove myself to my uncle, but the pieces fit too nicely together. He scorned my huohou and my capacity to master a difficult language. So I set fire to everything in sight and now own more than a dozen Chinese dictionaries.

Of course, there's more to it than that. I love throwing dinner parties and I love looking up Chinese characters, and I love the mala flavors of Sichuan food. I also love encountering and contemplating figures from the past, like Li Jieren and my uncle, and discovering relevance in their lives to mine. And I love standing in front of my wok, spatula in end, listening to my Huohou Spotify playlist, watching for the first tendrils of smoke to appear from my hot oil, and knowing that the moment of truth has arrived and it is time for the garlic and ginger and chili bean sauce... In my life, fire and Chinese are linked at the hip, so it's no wonder that eventually I combined the two in the form of passion for cooking Sichuan. For that there can be no regrets.

I have long had complicated feelings for my uncle, and the rigid formalities of Confucian patriarchy are one of my least favorite things about Chinese culture, but there are moments when it is appropriate to revere one's ancestors. This is one of them.