The basics:

1. Spatchcock a whole chicken (or more, if you’re feeling frisky).

2. Slather multiple tablespoons of doubanjiang under the skin of the breasts, thighs, and legs.

3. Lavishly sprinkle a mixture of cayenne, dry mustard, coriander, cardamom, cumin, turmeric, five spice powder, salt and Sichuan pepper on the outside of the skin.

4. Marinate, uncovered, in a refrigerator, overnight.

5. Grill for roughly an hour.

6. Devour.

This dish has many mothers.

In Sichuan people have been combining doubanjiang and chicken in multitudinous ways for centuries. The spice rub recipe (minus the Sichuan pepper) is lifted from one of my favorite cookbooks, Denis Kelly’s Pacific Grilling: Recipes for the Fire from Baja to the Pacific Northwest, but obviously has antecedents that date back to Indian subcontinental prehistory. My preferred technique for grilling a spatchcocked chicken was adapted from a J. Kenji Lopez-Alt tour-de-force published in Serious Eats. I learned how to separate chicken skin by watching a YouTube video. Fuchsia Dunlop’s The Land of Plenty informed me, nearly 20 years ago, that the best doubanjiang comes from the town of Pixian, in Sichuan.

We all stand on the shoulders of giants. In July, I wondered what a grilled chicken marinated in doubanjiang would taste like. So I did some experimenting and was delighted at the results. But it feels wrong to take credit. I am just happy to be a vehicle for this particular incarnation.

Listen! Spatchcock doubanjiang. Do you hear it? The promiscuous border-crossing? The poetry of hybrid fusion?

+++

Spatchcock is an English word of uncertain derivation reeking with down-to-earth Anglo-Saxon crudity. It refers to the process of removing the spine of a bird and then flattening the carcass -- a technique also known as butterflying.

But why whisper “butterfly” when you can declaim “spatchcock”?

Doubanjiang -- fermented fava bean chili paste -- is one of the most essential elements in the Sichuan larder. In Mandarin, all three syllables are pronounced with the sharp, peremptory “falling” fourth tone. It is therefore altogether appropriate to announce the arrival of this dish as if you are a drill sergeant calling cadets to account. Spatch! Cock! Dou! Ban! Jiang!

The payoff from their conjunction? Spatchcocking significantly cuts down on cooking times and results in juicy breast meat. And doubanjiang delivers all the umami indulgence one could ever desire.

+++

Some caveats.

1) If you are squeamish about handling raw chicken flesh, seek elsewhere for your grilled chicken satisfaction. Separating the skin from a chicken without tearing it or otherwise destroying its structural integrity is an intimate, hands-on process that rewards patience and sensitivity -- a job, or rather, a vocation, for people comfortable with negotiating feedback loops of liminal ambiguity. You must become one with the chicken -- you must listen to Zhuangzi’s butcher -- you must find the space between.

And then you must fill that space with doubanjiang, which is a messy business. A dirty, filthy business. A glorious, sensual business.

2) Some might consider the application of the Indian spice rub to be a case of gilding-the-lily overkill, but my interpretation of Sichuan culinary sensibilities always encourages me to say yes to more. When in doubt: default to complexity! Why not mix China with India? Spatchcock doubanjiang is the Kathmandu of grilled chicken, a place where continental plates and ancient civilizations collide.

3) I personally cooked this dish three times over the summer; once on a standard Weber grill, and twice over a wood fire in an outdoor fireplace. I also supervised, from a distance, the mass production of eight spatchcocked chickens (four marinated in doubanjiang, four marinated in a shawarma sauce) over mesquite charcoal in a fire pit. All the renditions came out delicious, but it was far easier to control the entire process on the Weber. Again: I refer you to J. Kenji Lopez-Alt’s grilling instructions for the nitty-gritty details.

And now, a word about doubanjiang.

In Chinese: qu. In Japanese: koji. In bastardized Latin: aspergillus. In English: mold.

According to William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi, the indefatigable chroniclers of all things soy, the first written reference in China to the use of mold in food preparation dates back to the third century BC.

Koji (qu, pronounced “chew”) is first mentioned in the Zhouli [Rites of the Zhou dynasty] in China. The invention of koji is a milestone in Chinese food technology, for it provides the conceptual framework for three major fermented soyfoods: soy sauce, jiang/miso, and fermented black soybeans, not to mention grain based wines (incl. Japanese sake) and li (the Chinese forerunner of Japanese amazake).

And then there are the non-soy foods, like doubanjiang! Like all fermented food products, doubanjiang is a mystery of heaven, the fortuitous result of ancient innovators who were bold (or desperate) enough to mess around with mold, and see what happens when bacteria go crazy. Because chili peppers most likely did not arrive in Sichuan until the 18th century, doubanjiang is a relatively late arrival to the fermented food shelf, but it swiftly established itself as an element of Sichuan cuisine every bit as fundamental as Sichuan pepper. For an entertaining deep literary dive, I recommend Yan Ge’s The Chili Bean Paste Clan, a tasty, if somewhat lurid novel about a family of doubanjiang makers.

A couple of notes on ingredients:

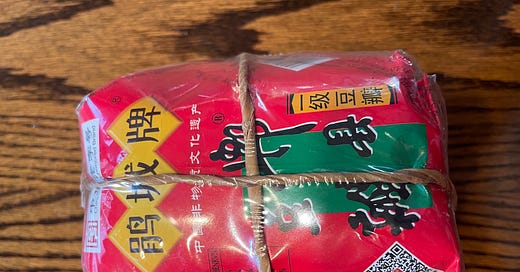

Chris Liang, who I suspect is the entrepreneur behind the bare-bones online Chinese ingredient emporium posharpstore.com, has a great writeup of the varieties of doubanjiang that hail from Pixian. Liang says that the “original version” Juancheng (“Cuckoo City”) brand that comes “in paper packaging has the deepest complex flavor.” I agree. I adore this doubanjiang. But be forewarned: it is extremely salty, and in the paper-and-twine packaging it arrives chunky-style, choc-a-bloc with whole fava beans. I usually run it through my Cuisinart before deploying.

Denis Kelly’s “Indian spice rub” recipe

1/2 teaspoon cayenne

1 teaspoon dry mustard

1/2 teaspoon coriander

1/2 teaspoon cardamom

1/2 teaspoon cumin

1 teaspoon turmeric

1 teaspoon Chinese five-spice powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

My addition:

1 teaspoon Sichuan pepper