The Secret of the Sichuanese iPad

Or, how the rise and fall of RCA explains everything. Part V of The Universal Commerce of Light

At a press conference on January 9, Li Wenqing, the vice governor of Sichuan, said that “two-thirds of the world's iPads, nearly 80 million laptops, and over 100 million smartphones were manufactured in the Sichuan-Chongqing region in 2024.”

Two-thirds of the world’s iPads. I heard a ghostly echo in the boast. In the spring of 1994, after writing a feature about Wired Magazine for the San Francisco Bay Guardian, I quit the Guardian and successfully pitched Wired on a story reporting how Taiwan established itself as a crucial player in the international supply chain for computing hardware. (Still online here, though you have to scroll down quite a bit.)

From my story:

“Taiwanese companies sell more motherboards, monitors, mice, and scanners than any other nation's companies. Taiwan today makes 20 percent of the notebook computers in the world. US chip designers can be made or broken by a Taiwanese manufacturer's decision to choose their products for inclusion on a circuit board.”

Two-thirds of the world’s iPads… 20 percent of the notebook computers in the world. Is Sichuan a new Taiwan? Is my life a closed circle?

One of the oddities undergirding this newsletter is that my intellectual fascination with Sichuan is rooted in my lived experience in Taiwan, where I ate my first bowl of mapo doufu, forty years ago. The history and culture of the two regions diverge in countless ways, and it is sometimes a challenge to unearth narrative threads that link both places, which means I am occasionally discomfited by the arbitrariness of the conjunction. What does this all mean? But in the resonance between the vice-governor’s brag and the cadence of my own thirty-year old prose I sensed a tantalizing glimpse of the big picture. Leibniz would be proud; my own universal language of meaning beckoned.

Sichuan’s iPads are manufactured at a massive Foxconn plant in Chengdu that employs 100,000 workers. Foxconn is a Taiwanese-headquartered company that has been operating in mainland China since as far back as 1988, following a business model perfected by the American electronics companies who began moving their manufacturing assembly lines “offshore” in the 1960s.

The first do so in Taiwan was an outfit called General Instruments, a key parts supplier for RCA, the Radio Corporation of America, a company whose enormous, literally world-changing, legacy in Taiwan beggars description.

The story of RCA is the story of how the consumer electronics industry began in the first place, how offshoring manufacturing in search of cheap workers irrevocably broke the post-WWII pact of mutual self-interest between capital and labor in the U.S., how East Asia became the electronics manufacturing center of the world, and how Taiwan became the producer of the world’s most advanced semiconductors.

I consider iPads in Chengdu, built in a factory owned by one Taiwanese company Foxconn – and stuffed with semiconductor chips manufactured by another – TSMC – and I can’t help thinking about how RCA, as a company, blew it all, while at the same time, one RCA engineer, a mainland China-born man named Pan Wenyuan, changed the destiny of an entire nation.

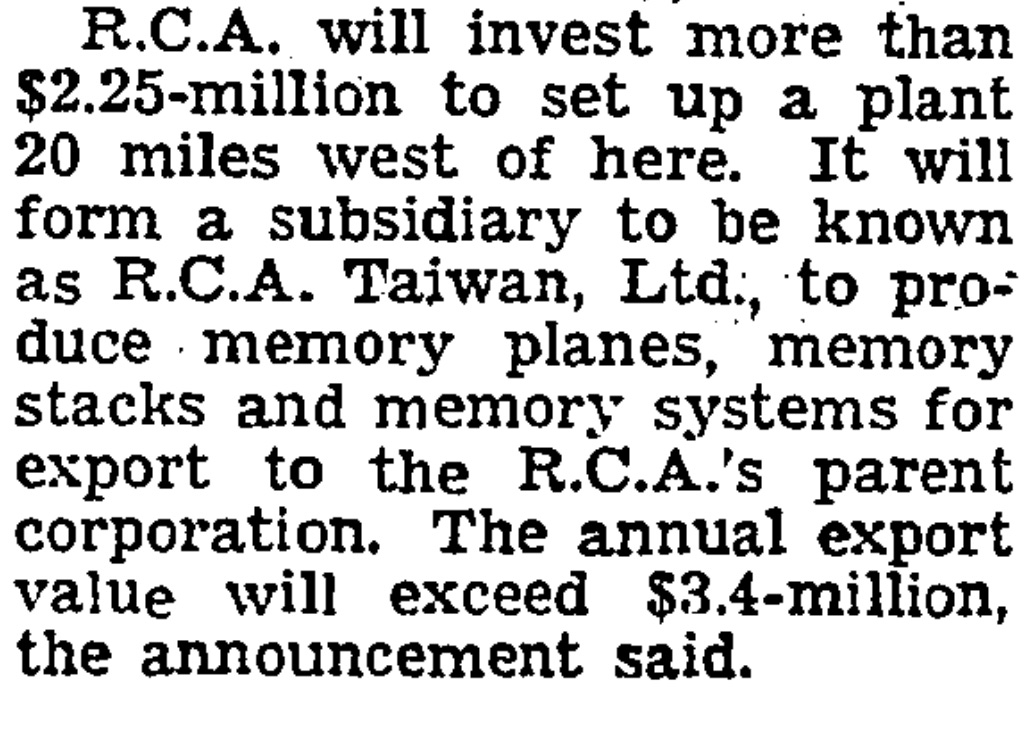

From the New York Times, April 27, 1967, datelined Taipei, Taiwan.

From my very own Present at the Creation: How Pan Wenyuan Connected Silicon Valley and China

In the 1950s and 1960s, David Sarnoff’s RCA was the premier consumer electronics company in the world. The company successfully commercialized both radio and television technology, created the ABC and NBC radio and TV networks, and was a pioneer in numerous other technologies. Its Princeton research laboratory, where Pan worked for decades, ranked with Bell Labs in influence. If any single company can be held responsible for ushering in our modern mix of culture and communications tech, it has to be RCA.

RCA was a primary manufacturer of the vacuum tubes designed for the ENIAC, the first programmable general purpose digital computer. RCA was a supplier for the Apollo program. RCA was the Apple of its time and David Sarnoff was its Steve Jobs.

Consider this memo written by Sarnoff in 1916, and tell me you don’t hear Steve Jobs waxing lyrical about his “bicycle of the mind”:

"I have in mind a plan of development which would make radio a 'household utility' in the same sense as the piano or phonograph. The idea is to bring music into the house by wireless.’ Sarnoff went on to describe the device, a ‘box which can be placed on a table in the parlor or living room, the switch set accordingly, and the transmitted music received. The offerings need not be limited to music...’"

But as the preeminent consumer electronics company of the mid-twentieth century, RCA was also one of the first American companies to face the inexorable economic logic of what later became dubbed, in a strictly computing context, Moore’s Law.

As Jefferson Cowie details in his fascinating Capital Moves: RCA's Seventy Year Quest for Cheap Labor:

A word on the idiosyncrasies of the consumer electronics industry is therefore in order. This sector suffers most acutely from one of the most enduring problems of free enterprise: overproduction. The constant revolution in materials and manufacturing has produced more goods ever more efficiently with fewer inputs, and this phenomenon has continued to lower prices and undermine the rate of return on investment for firms willing to enter this fiercest of industries. Since the advent of both radio and television, each generation of consumers has been able to purchase a better product at a lower price than the previous one. Crisper pictures, clearer sounds, and more compact sets have all been delivered to consumers with a shrinking price tag. With a relentless downward pressure on production costs, the search for cheap labor has held a pivotal position in firms' strategies to beat their competitors. This pressure has placed the burden of low prices on the shoulders of people toiling on an assembly line that stretches from New Jersey to Chihuahua.”

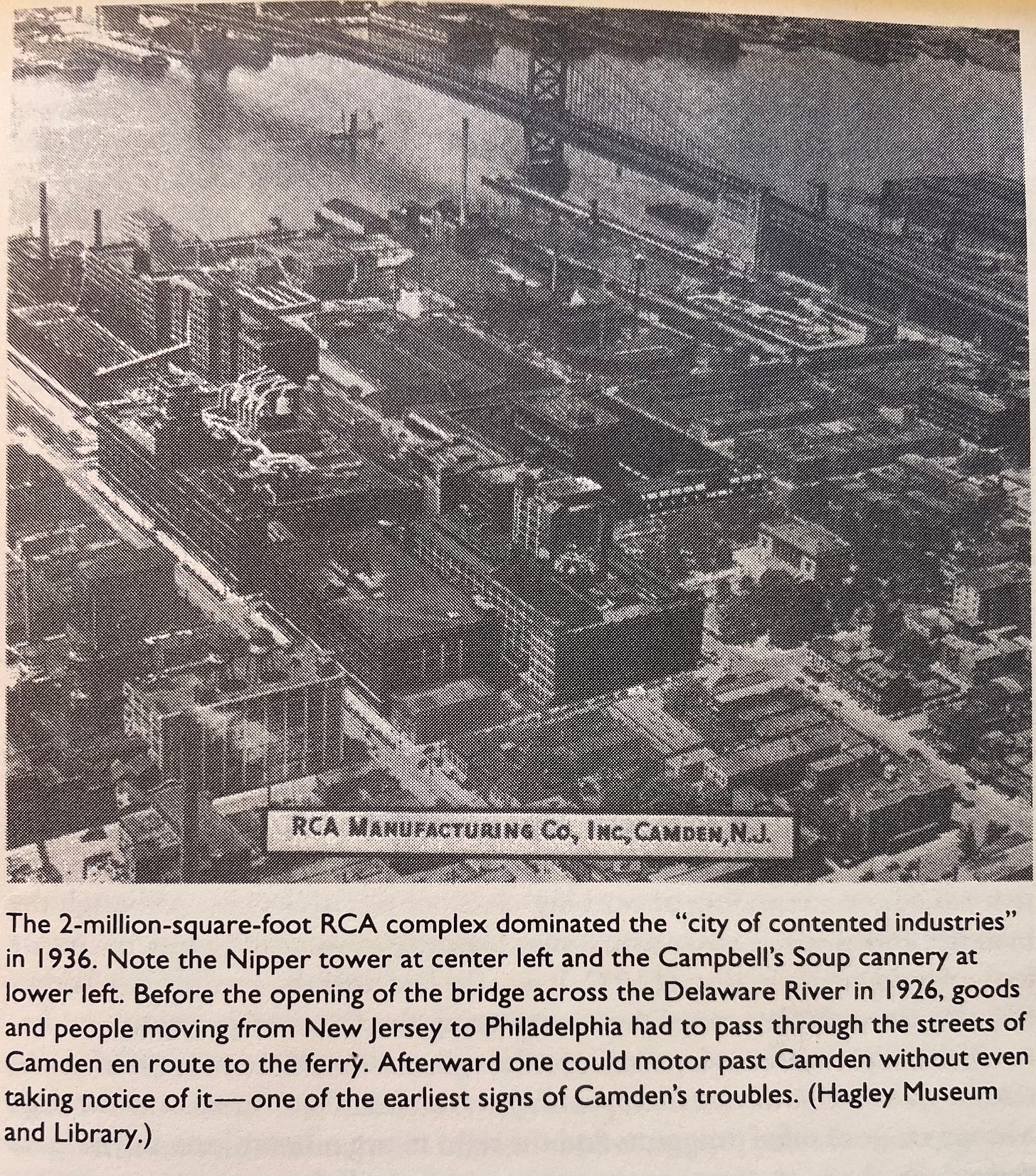

When the young women who toiled in RCA’s Camden, New Jersey factories started joining labor unions, RCA moved its TV manufacturing operations to Indianapolis, Indiana. When white Indianapolis workers started to get obstreperous, RCA switched to exploiting African-American labor in Memphis, Tennessee. As competition from Japan ramped up, (due in part to RCA’s willingness to license its technology to anyone who wanted it) making TVs in the United States became ever-more challenging. So in the late 1960s RCA set up operations in Mexico and Taiwan. By 1974 RCA was Taiwan's biggest exporter, sending millions of color televisions back to the States to feed America's boomer TV generation.

"As they always did,” writes Cowie, “the RCA executives sought not only a place with an economically weak labor force and a limited industrial culture but also the most marginal and economically vulnerable workers within that geographic space."

In Taiwan, RCA’s irresponsibility led to disastrous consequences for the workers, most of whom were young women.

"At its peak, RCA had more than 30,000 workers. In RCA's Taoyuan plant, female employees worked in three shifts around the clock. The company had ten buses to bring them from the nearby countryside and poor veterans' communities every day. RCA also provided nine dormitories to accommodate female workers who came from farther away (the middle and southern parts of Taiwan). All the girls living in these dormitories used ground water polluted by organic solvents from RCA's plant. "

"More than 1,000 former RCA workers have developed liver, lung, colon, stomach, bone, nasopharyngeal, lymphatic, and breast cancers, plus various tumors. Medical experts have indicated that the former RCA workers cancer rate is 20 to 100 times higher than that of the general public."

In the end, RCA’s strategy failed. Part of this had to do with Sarnoff’s ill-conceived attempt to turn RCA into an all-purpose corporate conglomerate involved in businesses that had nothing whatsoever to do with consumer electronics: RCA’s buying spree included the rental car company Hertz, the book publisher Random House and the real estate company Cushman & Wakefield…. Part of it was RCA’s dismal failure to win a share of the computing market. Notwithstanding its intimate connection to the earliest days of American computing, RCA ended up losing vast sums of money getting clobbered by IBM. Part of it might simply be because chasing cheap labor is a long-time loser’s game.

As Cowie writes:

“Some observers believe that if the company had been investing in its productive capabilities rather than buying other companies and searching out cheap labor, both worker's and the industry's future would have been quite different. By moving production abroad so early in the face of international competition, the industry made an implicit decision to embark on a long-term strategy that would eventually end domestic production. ‘A decision to battle imports with automation and radical technological change’ earlier on, argues one industry analyst, ‘could have resulted in a dramatically different outcome.’"

There exist few better proofs of the proposition value of “investing in productive capabilities” than the decision of Taiwan’s government in the 1970s to target the semiconductor industry as a focus of industrial growth.

Amazingly, this too is an RCA story!

Enter Pan Wenyuan.

As I wrote seven years ago for Medium in a story that I’m pretty sure is now behind a paywall, Pan Wenyuan was a radio engineer in mainland China who received a government scholarship to attend graduate school in the United States. He ended up at Stanford in the 1930s, where he was a classmate with Hewlett-Packard founders William Hewlett and David Packard (he co-wrote a paper with Hewlett about what became HPs first product, the RC 200A oscillator.) After World War II he got a job as a research scientist at RCA, where, among other things, he worked on circuit designs for televisions and collected 30 patents in his own name. Although he did not return to mainland China after the Communist revolution, he had contacts at high levels in the Taiwanese government, and when they asked him what technologies Taiwan’s government should be investing in, he’s the guy who said: semiconductors.

Premier Sun appointed Pan as head of a Technology Advisory Council (TAC) to steer Taiwan’s efforts to implement his plan. The first step: acquiring the necessary technology to get started. After being rebuffed by a roll-call of U.S. semiconductor companies, Taiwan’s government ended up paying RCA $10 million for a semiconductor technology transfer agreement. By this time, Pan had retired from RCA, specifically to avoid conflict of interest issues, but it seems likely that he had some influence on the decision.

Next, Pan recruited a cadre of 37 twenty-something Taiwanese electrical engineers to engage in an intensive year-long training program at RCA’s U.S. facilities. The so-called RCA 37 returned to Taiwan and built a government-funded chip fabrication facility that immediately started supplying Taiwan’s nascent electronics industry with the vital innards for electric watches and calculators — and, eventually, personal computers. Many of the RCA 37 went on to found their own chip companies, eventually thrusting Taiwan to the front ranks of the world’s semiconductor industry.

It's worth noting here that despite a very early start RCA failed to make semiconductors a profitable business, and the technology that the company was licensing to Taiwan was hardly cutting edge. The company was in steep decline; the licensing deal was a quick cash grab. And yet Taiwan’s young engineers managed to learn enough from RCA’s outmoded tech to set their county on a path that would eventually reach the absolute summit of the global semiconductor industry.

An ancillary point: the story of how Henry Ford paid his workers high wages, thus ensuring that they would have the wherewithal to buy Ford cars, is considered a classic example of a win-win relationship between labor and capital. RCA did the opposite.

Cowie, once more:

“In contrast to the Keynesian formula that supported the postwar boom, the interests of firms, which initiated cheap foreign labor strategies, and those of workers, who wanted to maintain a high employment level, began to diverge. This change in the meaning of ‘foreign trade’ for U.S. labor marked the beginning of the division between the growth strategies of major U.S.-based corporations and the interests of U.S. workers…. ‘As labor came to be seen more as a production cost to be minimized rather than a source of final demand,’ explains Patricia Wilson, ‘the social contract underlying the mass production model was fundamentally undermined.’"

In terms of domestic politics in the U.S. over the past fifty years, the long-term impact of breaking that social contract hardly needs belaboring. Why did white working class men vote for Donald Trump? You can blame RCA and its brethren.

What fascinates me about the phenomenon of the Sichuanese iPad is how its physical reality encapsulates both sides of the RCA story. Foxconn is the offshorer, seeking lower wages and a workforce it can shamelessly exploit, while the TSMC chips inside those iPads – products of a technological process that Communist China has yet to master -- signify the paramount importance of constantly investing in more advanced productive capacity, of being smart, and not just greedy.

But that’s not the last layer of this onion. The China that sent Pan Wenyuan abroad in the 1930s was a China obsessed with its self-perceived inferiority to the West. One of the raging questions among the Chinese intelligentsia of the time was whether China’s own culture made it noncompetitive. There was a widespread consensus that China needed to dump its written language in order to catch up with the West. The writing system that Gottfried Leibniz once imagined might be a model for his universal language was deemed hopelessly inefficient by its own users!

Pan Wenyuan was sent to America to learn the secrets of Western success. And it worked. A Chinese engineer ended up orchestrating the process by which Taiwan became the world’s leader in an all-important technology. And Taiwan, incidentally, never even went so far as to simplify its Chinese characters, much less abandon them. It seems as if the writing system wasn’t the problem.

I didn’t initially intend my musings on Sichuan’s iPads to be a full-fledged installment in this ongoing series on Leibniz, the Chinese computer, and the Book of Changes. I initially thought of it as yet another cool footnote, a quick link between a 30-year-old Wired story and a press conference held last week that I could toss off with a few hours work. But as I tried to whip it into shape, I began to perceive through the myriad convolutions that the Sichuan iPad was recasting my original research question – did the Book of Changes influence Leibniz’s invention of binary arithmetic and thus exert some influence on the birth of computing? – in an entirely new light. The answer to the original question was no. But who could deny that any computer with a Taiwanese-manufactured chip inside of it is at least in a partial sense a “Chinese” computer, thanks to one Chinese engineer named Pan Wenyuan and another mainland born Chinese engineer named Morris Chang, the founder of TSMC. (Who, incidentally, I interviewed in person for my Wired story 30 years ago, but to my enduring dismay, did not manage to include a quote from in the actual story.)

One last note: in the course of rereading my old Wired article I glanced at my archaic bio at the end of the piece, and realized that somehow, chasing Leibniz and all those Sichuan iPads had led me right back to the beginning of my career.

My suspicion is that there is nothing arbitrary about any of this.

This is a wonderful piece, Andrew, which I hope you will find a way to get to more readers.

I'm also pleasantly reminded that we share an abiding interest in Sichuan that for both of us was originally kindled in Taiwan, most likely over similar bowls of mapodoufu at similar establishments in Taipei, but mine was 55 years ago.

The contrast between Ford's strategy and RCA's is heartbreaking. Will we ever acknowledge the societal costs of exploiting workers in order to boost profits?