Richard Nixon's Anchovy Problem

A story of price signals, seed collectors, extreme climate events, and war.

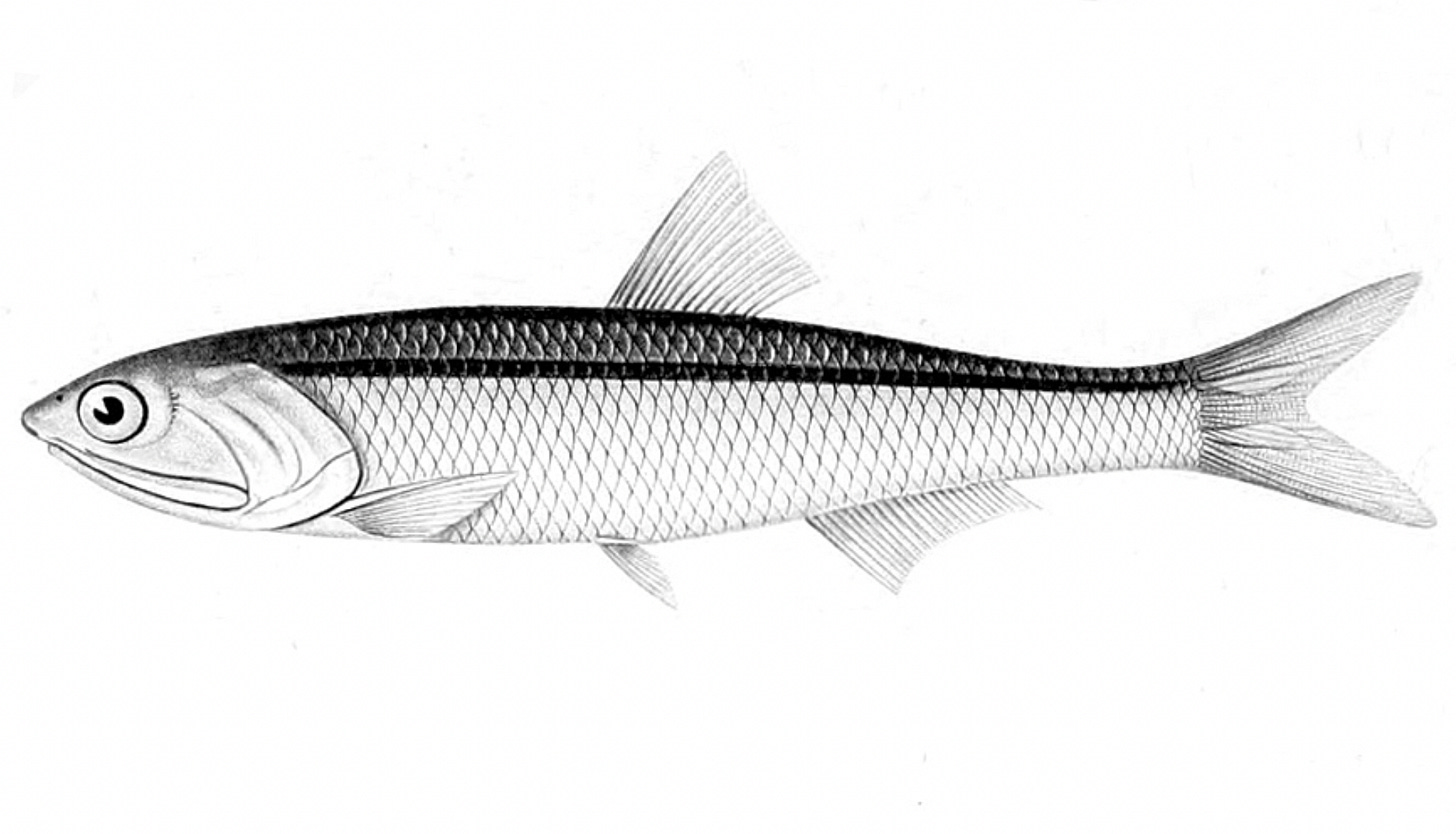

In the winter of 1972-1973 an El Nino event causes a sharp rise in ocean temperatures off the coast of Peru. The change in conditions eviscerates Peru’s anchovy harvest. This is a big deal: In 1970 alone, Peru harvested 11.2 million tons of anchovies, most of which ended up as animal feed for pigs and chicken and cattle in North America and Europe. In response to the sudden disappearance of Peruvian fishmeal, prices for replacement feedstocks shoot up. One popular substitute is the protein-rich soybean. Soybean prices triple in 1973.

That’s good news for American farmers, who by the second half of the twentieth century produce the majority of the world’s soybeans. But it’s bad news for customers at the butcher counter. For politicians, there is never a good time for food price inflation, but in the summer of 1973, President Richard Nixon is fighting for his political life fending off Watergate investigations and Congressional opposition to his conduct of the Vietnam War. The last thing he wants to see is American consumers pissed off by the rising price of a pound of beef.

On June 27th, 1973, Nixon orders an immediate ban on soybean exports.

Japan freaks out. Japan depends on the U.S. for 70 percent of its soybean supplies, not just for animal feed but also for the enormously culturally symbolic production of soy sauce and tofu and miso. Nixon’s action is taken without warning and at first it appears that existing trade deals will be summarily nullified. Japan’s government wastes no time; preliminary negotiations already underway with the aim of boosting agricultural trade with Brazil are swiftly expanded into a plan to fund soybean cultivation in South America. Half a billion Japanese dollars and 20 years later, Brazil has been transformed from a negligible supplier of soybeans to global markets into the world’s biggest exporter of “the miracle bean.” Huge swathes of the Cerrado, a vast savannah five times as large as all of Japan, has been sculpted into soybean plantations. In recent years, the flow of soybeans from Brazil to China has constituted the largest exchange of any agricultural product between any two countries in the world. Nixon’s rash act, which ended up rescinded within months, is directly responsible for the creation of a dominant competitor whose interests are aligned against U.S. farmers.

Brazil’s soybean surge, in turn, inspires its neighbors to the south and west -- Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina, the so-called “Southern Cone” -- to transform their own economies and remake their own landscapes into soybean monocultures farmed for export. To pick just one astonishing statistic: By 2020, half of all arable land in Argentina is planted with genetically modified herbicide-resistant soybeans.

A climatic event. A fishery collapse. A soybean price spike. A desperate political maneuver by Tricky Dick. A Japanese counter-move. The Brazilian Cerrado becomes a South American version of Iowa. Displaced cattle ranchers looking for new grazing pasture set fire to the Amazon rainforest.

Cue, inevitably, more climatic events.

And this wasn’t even the first, or even the most consequential, intersection between a fishery crisis, Japan, and the soybean.

It would be no exaggeration to say that Japan’s economic expansion in Manchuria had for one of its major objects the securing from possible interference by an enemy of this wondrous bean. She has invested about $12,000,000 in Manchuria’s bean milling industry alone. Her railroads there, and her ocean freighters, profit by transporting it. All the Manchurian railroads have special facilities for handling bean products. At Dairen, the Japanese port in the Kwantung Leased Territory, special tanking arrangements have been made, connecting the South Manchuria Railway with steamers. Huge bags of beans and great stacks of bean cake shaped like cartwheels are piled high on the wharves at Dairen and at every railroad station in South Manchuria. In Manchuria, the bean is ubiquitous.

George Sokolsky, “The Bean Behind Manchuria’s Struggle,” New York Times, March 20, 1932.

The modern history of China’s Northeast was inextricably tied to that of the soybean. The humble bean shaped the lives of the region’s residents, luring settlers, merchants, speculators, and laborers to the region, and influencing social relations between them. It played a central role in the complex geo-political rivalries that gave the region the reputation of the “Cradle of Conflict.” Japan and Russia built their empires upon the soybean, and Chinese powerbrokers used it to erect their own centers of power. The trade in soybeans linked Manchuria and its residents to other parts of China and the world, and affected how people in other parts of the world perceived the region. In the early twentieth century, it facilitated the region’s incorporation in the global capitalist system, subjecting its economy to the cyclical booms and busts of global commodity trades.

Richard Evan Wells, “The Manchurian Bean: How the Soybean Shaped the Modern History of China’s Northeast, 1862-1945.”

In the 1880s, a little less than a century before the El Nino event that annihilated Peru’s anchovy harvest, the pilchard and herring fisheries off the coast of Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan’s main islands, also crashed, likely as a result of over-fishing. This posed a quandary for Japanese farmers, who, as they strove to increase agricultural output to keep up with population growth, had come to rely on fishmeal as a key source of fertilizer. Chinese merchants living in Japan had a ready solution: Manchurian beancake. The switch flipped with amazing speed. “In 1903,” writes Richard Wells, “Japanese farmers applied 195,000 tons of bean cake fertilizer on their fields, which accounted for an astounding 36 percent of all fertilizer applied on Japanese farms that year.”

Japan’s soybean fertilizer craze, argues Wells in The Manchurian Bean, was a determining factor encouraging Japan’s imperial aggression in (and ultimate annexation of) Manchuria. “The soybean’s versatility as a protein-rich foodstuff, fertilizer, and source of industrial raw material,” writes Wells, “led Japanese policymakers to see Manchuria as an indispensable part of the Japanese Empire and one of the central pegs of Japan’s wartime economy… The influx of cheap bean cake fertilizers from Manchuria allowed for large increases in agricultural production in Japan during the early twentieth century, which spurred population growth, industrialization, and urbanization in the country.”

We have previously seen that the soybean was a commodity in China as far back as the Han dynasty, and that soybean cake fertilizer was commercialized within China towards the end of the Ming dynasty. We have examined the stories of some of the earliest Westerners who proselytized the wonders of the soybean. But Japan’s embrace of Manchurian beancake marks the moment when the soybean finally becomes a major player on the world stage. This is when the Soyacene -- to borrow Claiton Marcio da Silva and Claudio de Majo’s handy encapsulation of “the narrative of soybean production in the age of the Great Acceleration” – begins. This is when the soybean starts to become an indispensable input for advanced capitalist society logistics.

Japan’s stunning victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 is well known for announcing the emergence of Japan as a global power that could threaten the dominance of the West. A little less publicized has been the extent to which that war was at least in part motivated by Japan’s desire to solidify economic control over Manchurian soybeans. The soybean’s global breakout turned out to be a side effect of the war. Both sides in the conflict depended on the soybean as food for men and horses, which in turn stimulated demand for the locally produced product. After the war, supply far exceeded what even Japan’s busiest farmers could consume, thus incentivizing soybean traders to look for new markets.

In 1909, four years after the end of the Russo-Japanese war, “a shortage of cottonseed and linseed struck the English oilseed market,” writes Wells. “Oilseed crushers in the English port cities of Hull and Liverpool began looking for cheap substitutes.”

The original consumers of soybeans in Europe were not farmers, as was the case in China and Japan, but industrial seed crushers, who used soybeans not as fertilizer but as a source of vegetable oil, which was used by European manufacturers as a raw material in the production of margarine, soap, paint, and a range of other goods essential to modern European society. The arrival of Manchurian soybeans in Europe marked Manchuria’s incorporation into the nascent global trade in oilseeds.

The European trade introduced a new, unsettling level of unpredictability into Manchuria’s commercial world. English seed crushers’ discovery of the Manchurian soybean transformed it into an oilseed with a global market, making demand for the commodity, and thus its price, subject to a complex interplay of a myriad global factors, including, but not limited to: currency exchange rates, the London bullion market, maritime freight rates, insurance rates, the American cotton harvest, the price of linseed oil, tariff rates, and stakeholders’ predictions of future market conditions.

Between 1907 and 1929, Manchurian soybean exports grew by 17,000 percent, from 160,000 to 2.72 million tons. “The Manchurian Bean” became world famous.

From a historical point of view, the global supremacy of soybeans from Northeast China makes perfect sense. Soybeans are believed to have been first domesticated in this general region. Soybeans were therefore perfectly adapted to Manchuria’s climate and no one had more experience raising soybeans than the Chinese peasants who emigrated to Manchuria in the 18th and 19th centuries. As the world became more tightly integrated into an economic system where price signals in one region near instantaneously spawned dramatic responses in another, the soybean’s premier attribute – its bang for the buck – made it incredibly valuable.

But what international commodity markets give, they can also take away.

Which means it is time for the United States to enter the soybean group chat.

In the stream of agricultural history there are few events more exciting than the dizzy rise of the soybean in the United States.

"Young fellow," [Dr. C. V. Piper] used to say, "these beans are gold from the soil. Yes, sir, gold from the soil. One must truly stand in awe of their potential power in the life of the western world."

Edward Jerome Dies, “Soybeans: Gold From The Soil”

The importance of the soybean lies largely in the fact that the seeds can be produced more cheaply than those of any other leguminous crop. This is due both to its high yielding capacity and to the ease of harvesting… Extensive data show that the United States can successfully compete with the Orient in raising soybeans because the use of machinery counterbalances the cheaper Oriental labor.

Leo Gilbert Windish, “The Soybean Pioneers”

It is difficult to overstate the chaos that routinely engulfed China in the early 1930s. A single flood in 1931 killed millions of people when the Yangzi overflowed its banks. Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai were bunkered down in the province of Jiangxi, fending off furious attacks from Chiang Kaishek, whose Nationalist armies were also fighting with regional warlords in the Central Plains. And all the while, Japan was preparing for its full-scale invasion of China, which it finally launched after a staged provocation in the city of Mukden in 1931.

In the middle of this mayhem, in an example of privilege that is truly mindboggling to comprehend, two American horticulturists named Palemon H. Dorsett and William Henry Morse spent 18 months criss-crossing Japan, Korea, and China collecting thousands of different varieties of soybean seeds. Most of the work was actually done by Morse, later to be dubbed “the father of soybeans in America,” as Dorsett came down with pneumonia and had to be sent off to Beijing for rest and recuperation, but the mission is universally referred to by soybean historians as “the Dorsett-Morse expedition.”

Today, mindful of intellectual property rights, we might be inclined to view Dorsett and Morse’s activities as blatant acts of “bio-piracy” but by 1930 it had been standard practice for many decades for representatives of Western powers to gather any and all biota that might seem interesting and send it back home for analysis and exploitation. Dorsett, who was 64 years old at the time of the expedition, was a grand old man of the trade, previously having been responsible for the first propagation in the U.S. “of the tung oil tree, date palms, Japanese flowering cherry trees, oriental bamboos, [and] east Indian mangos.” Morse was singularly focused on the soybean. He had written his first article on the soybean as a 26-year-old in 1910. He founded the American Soybean Association in 1919. Under his leadership the Dorsett-Morse expedition brought back an amazing total of 4451 different soybean “accessions” to the U.S.

Dorsett and Morse weren’t the first Americans to collect soybeans from China. But no one else managed to be quite so thorough, or strike a similarly symbolic note. Because the year when Dorsett and Morse arrived in East Asia, 1929, turned out to be the peak of the Manchurian soybean’s arc.

In 1929, American farmers raised a mere nine million bushels of soybeans, a pittance compared to the 2.6 billion bushels of corn harvested the same year. But just ten years later, American farmers raised 91 million bushels of soybeans, an amount almost exactly equal to the 1929 Manchurian export record.

Manchuria, racked by war and revolution and cut off from its previous export markets by the division of the world into communist and capitalist spheres, never recovered its former international soybean glory. U.S. farmers, leveraging an unprecedented combination of agronomic science, industrial scale, and technological advances, seized control of the means of soybean production and established themselves as the most prolific exporters of soybeans in the world for decades… until that fateful day when President Nixon instituted his ban.

A fishery collapse in the 1880s starts Japan on its fateful path to world war. A bad linseed harvest in Argentina combined with a bad cotton harvest in Egypt in 1909 elevates the soybean into a valuable industrial commodity. An El Nino event in 1972 precipitates the transformation of South America’s Southern Cone into Soylandia.

Really enjoyed this. Has the definitive book been written on the soybean as a driver of global history? One of those Kurlansky "Salt"-type books?

Wow—I’m persuaded. I love tofu and always season steak with soy sauce, but had no idea that I was yet another tiny servant of this majestic power.