"In the Darkness, I Pour Wine"

The distance between a civilization’s peak and its collapse can be as short as a single love affair gone wrong. Climbing Emei Mountain, Part I

“Omei is the famous mountain of the Land of Shu”

The Omei Illustrated Guide Book

Emei was the name of the Sichuan restaurant that changed my life on my first day in Taiwan in 1984.

In the pioneering wuxia novel, Sword Heroes of the Shu Mountains, the good guys and gals, a motley collection of bad ass magic-sword wielding transcendent masters and disciples, are referred to as the Emei pai – with “pai” usually translated as “faction” or “clique” or “school,” -- because their glorious “grotto heaven” cave hideouts are clustered in and around Mount Emei.

The eighth century poet Li Bai, who was raised in Sichuan, wrote a poem about climbing Mount Emei.

Of the many fairy mountains in the Shu State

Omei afar is truly hard to compare

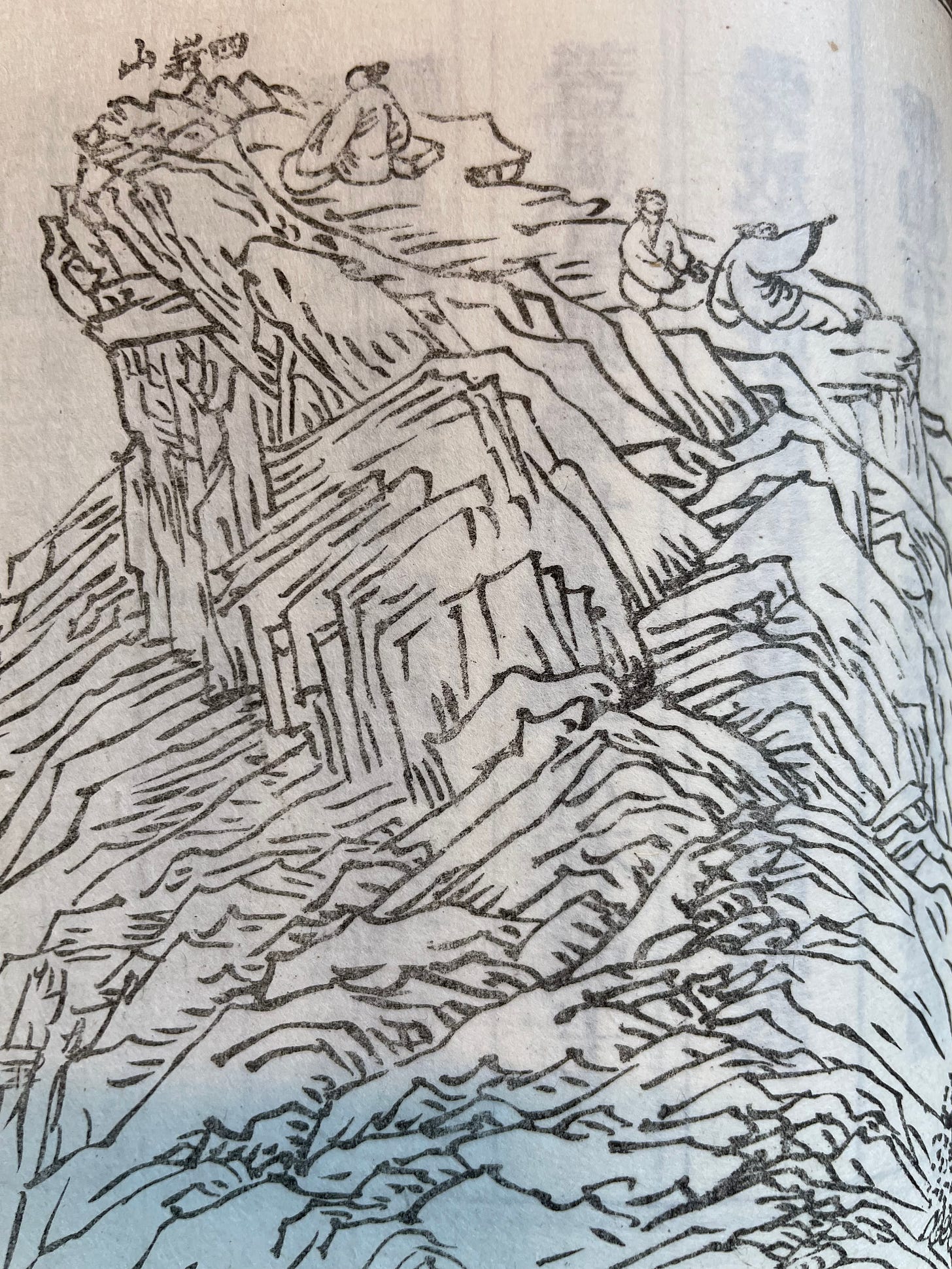

Rambling around, I attempt to climb and survey the scenes

How can I see all of its supreme marvels?

Blue-tinged blacknesses unfold against the heavens,

Multi-colored patterns arise as if from a painting.

Rarified, I relish the purple auroras,

Indeed have attained the secrets of the damask satchel.

Among the cloud I sound my rose-gem syrinx,

From atop a stone, I finger the gemmy zither

My life long I’ve had this trivial aspiration,

Happiness and joy are complete hereafter.

As if the misty countenance appears on my face

Dusty entanglements have suddenly disappeared.

If I encounter the Lord on goatback,

Hand in hand, we’ll fly towards the white sun.

(Translated by Shi Mingfei)

It pleases me that a popular branding exercise for Sichuan restaurants around the world is the name of a mountain that has been sacred to Daoists and Buddhists for millennia. Mount Emei goes hard. In the Baopuzi, a venerable Daoist tract written by the alchemist and philosopher Ge Hong in the fourth century, we are informed that Mount Emei is “unequivocally sanctified as the primary site where the Yellow Thearch encountered the Sovereign of Heavenly Perfected (天真皇人) and achieved the Dao.”

The Yellow Thearch, also known as the Yellow Emperor, is the original huangdi (皇帝), the supposed initiator of Chinese civilization. That’s a bold claim for Mount Emei. As traditionally imagined by the inhabitants of the Central Plains, where the Shang and Zhou dynasties originated, “Chinese civilization” most certainly did not start in Sichuan. There are no archaeologically valid connecting points between the Bronze Age glories of Sanxingdui and the Yellow Emperor.

But such quibbles are immaterial to my purpose here. In the newsletter series on which I am now embarked I will be roaming free and unfettered in realms of fantasy and myth; I will be investigating the alchemical quest for immortality, the spiritual power of magic mountains, and the poetry of transcendence. I will pay heed to what people living in medieval China believed, and leave the debunking to others.

I ate my first mouthful of mapo doufu in a tiny, hole-in-the-wall restaurant in Taipei named Emei. It tickles me to imagine that every bite of mapo since that memorable day could be construed as honoring the primeval creation of Chinese civilization and the achievement of Dao. It’s just that tasty.

And of course, every time I apply heat to my ingredients when I cook my own mapo, I am also engaging in an alchemical practice akin to the experimentation of those Daoist hermits who sequestered themselves away in caves on Mount Emei while mixing melted cinnabar and lead in their pursuit of transcendence.

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

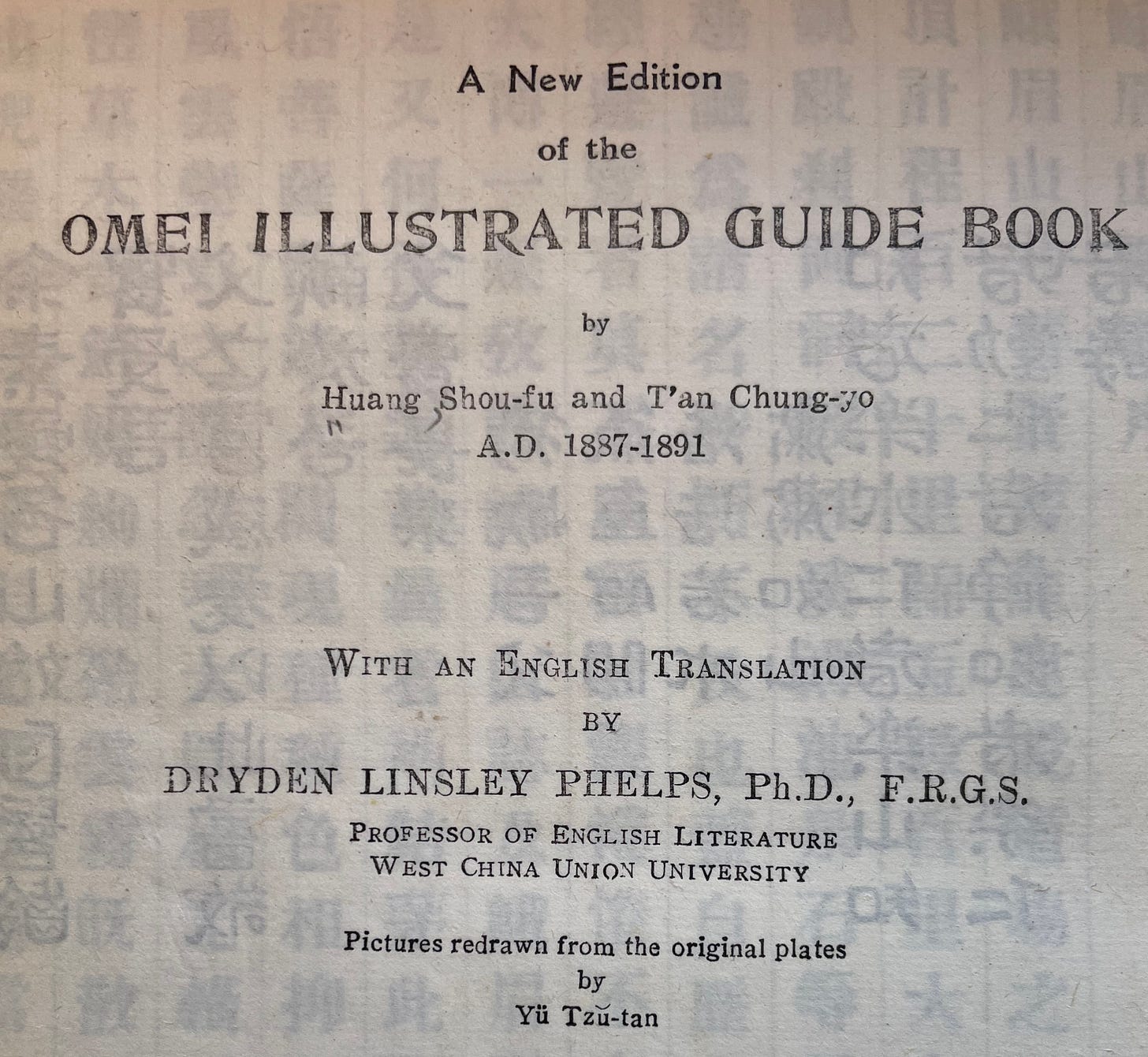

In the course of my research for this project I discovered an amazing artifact in the UC Berkeley library: a bilingual Chinese-English edition of the Omei Illustrated Guide Book, published in 1935. It is the handiwork of an American missionary, Dryden Linsley Phelps, who spent decades in Sichuan. When he wasn’t teaching or preaching, he appears to have been climbing the local mountains.

“What a paradise to the lover of heights is Szechwan! Most of the western half of the province seems to stand on end! What can equal the majesty of Omei’s gigantic brow? Who has not felt the other-world sublimity of the Minya Kunga and her sister snows, when dawn touches these gleaming cones of ice? My first summer I joined the West China Border Research Society Expedition to Rumichangu and Badi Bawang. Early in the afternoon of a perfect day we reached the 16,4000 foot Konker Pass. To the west lay the ramparts of the Tibetan tableland; elsewhere around the horizon rose stupendous snow cones, like the broken teeth of a vast ivory comb. Such was my introduction to the Land of Shu.”

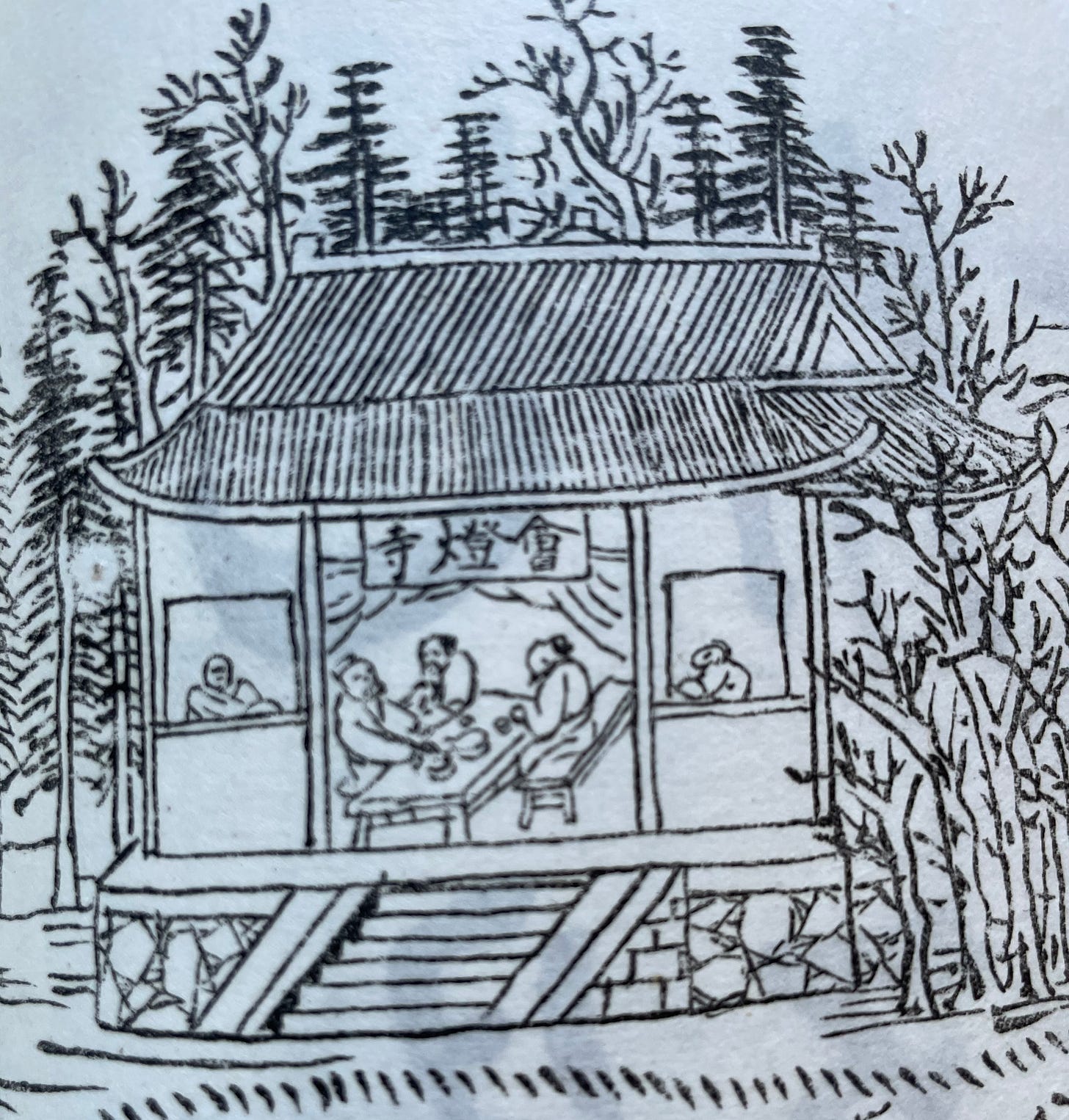

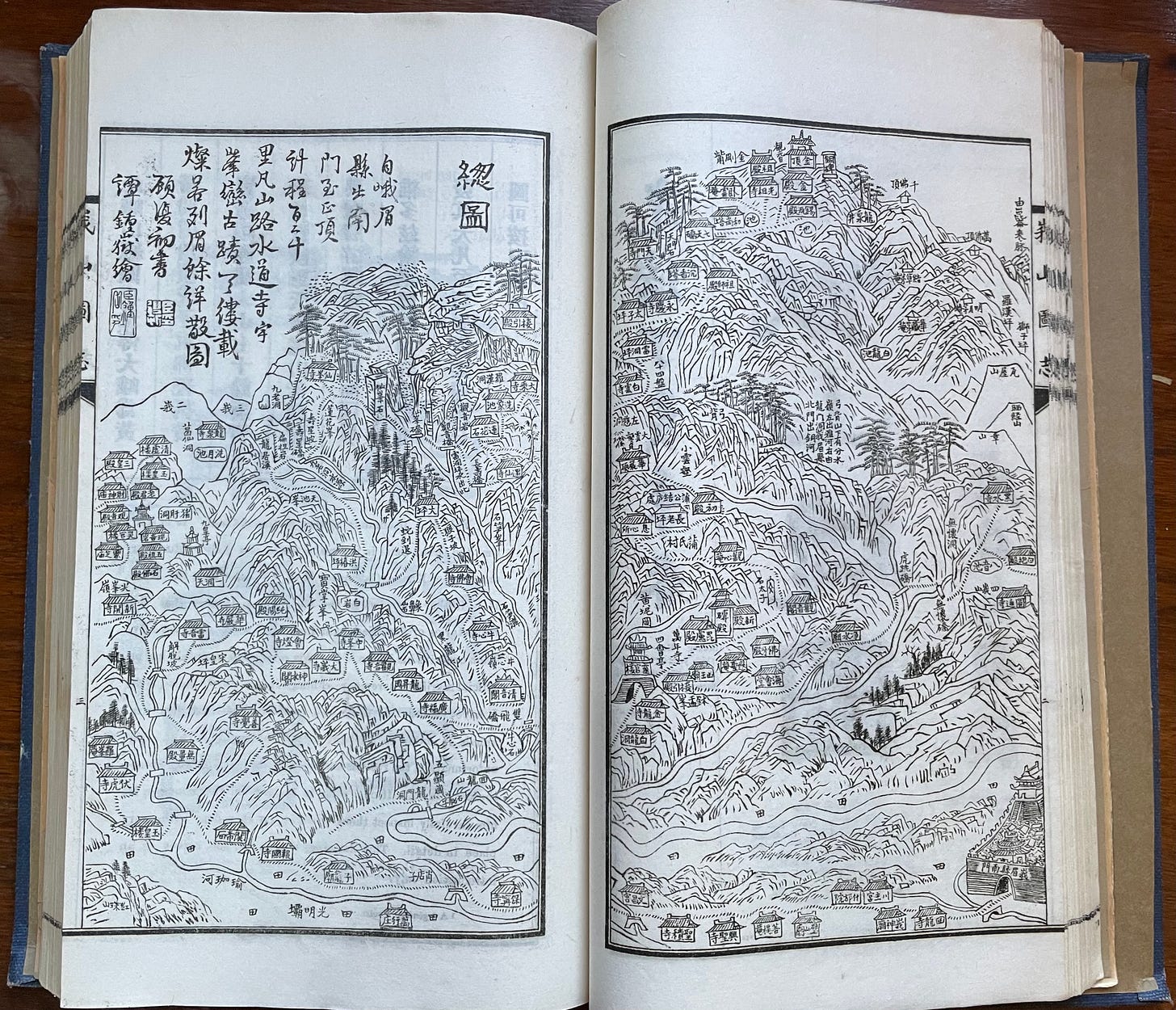

The Omei Illustrated Guide Book is a work of scholarship, beauty, and love. It features sixty extraordinary drawings of various aspects of the mountain, poems in honor of its majesty and mystery, and a wealth of information about the scores of temples and shrines and natural wonders that festoon its slopes. The opening illustration is almost too detailed to comprehend.

It seems like a miracle that this book is in my home office right now, on a ninety- day loan. It should be in a rare book room, to be handled only with white gloves and peered at through a magnifying glass. Glancing through its pages, lingering on The Pool of the Bathing Elephant and the Flowers of Sulphur Cavern and the Monastery of the Immortals Peak, I feel only the thinnest of membranes separating me from a land of marvels.

Poem 23, from the Omei Illustrated Guide Book

In the upper chamber of the Ethereal Tower the band of Immortals was received;

It belongs to another realm, a cavern abode of celestial spirits.

I heard a tale of the Yo Yang guest, thrice overcome with wine:

Chanting aloud his rhymes, he flew aloft – almost up to the azure peak.

In The Sword Heroines of the Shu Mountains, (originally serialized in Chinese newspapers in the 1930s, which means it is possible that our Omei Illustrated Guidebook translator, Dryden Phelps, might have read it fresh off the presses), protagonists aligned with both good and evil are frequently engaged in a quest for a particular daoshu (道書), an arcane text that might include the formula for creating a magic weapon or the instructions on how to execute a particular path to transcendence. Sacred cookbooks, if you will. In video game terms, they facilitate “leveling up.”

Perhaps the Omei Illustrated Guide Book is my own daoshu, bequeathed to me by a beneficent immortal and packed with recipes that will assist in my own path to… somewhere.

How, exactly, did I get here? In retrospect, it seems inevitable, but it came to pass without much forethought.

I started reading The Sword Heroines of the Shu Mountains last June. (As of last night, I have completed 27 percent of its 5000 pages!) At first, the exercise seemed little more than a clever way to combine one of my favorite guilty pleasures – reading fantasy fiction – with the edifying task of Chinese vocabulary acquisition. The great majority of action takes place in the Sichuanese mountains, those “broken teeth of a vast ivory comb,” shortly following the end of the Ming dynasty, so there is at least one connecting thread to my overall research project.

But even though I occasionally thought about composing a fun footnote about Sichuanese restaurants named Emei and a fantasy saga in which the heroes and heroines live on Mount Emei, I have so far struggled to find a more substantive way to connect my latest Chinese reading exercise to the themes that have emerged in this newsletter. Occasionally I question my self-indulgence. There are other texts on my desk -- a recently acquired history of Sichuan food by a leading Chinese food historian, and a well-reviewed novel set in Chengdu in the 1980s – that might better reward my study than a narrative full of debauched Buddhist monks, sentient orangutans and vultures, and flying sword air travel.

But the flow goes where it wants. As I attended to bill-paying work over the last couple of months, I occasionally carved out time to follow a trail that began with the most unexpected serendipitous outcome of my Leibniz explorations, the discovery of Kidder Smith’s fantastic book about the poet Li Bai, Li Bo Unkempt.

The footnotes to Li Bo Unkempt excavated a cascade of rabbit holes. One footnote, as I reported in The Dao is a Gigantic Glass of Beer, took me to Ed Schafer’s book about Medieval Daoism, Pacing the Void. Another introduced to me an article discussing Li Bai’s poem about climbing Mount Emei. A third pointed me to an essay by Thomas Michael, Mountains and Early Daoism in the Writings of Ge Hong, (the aforementioned fourth century alchemist and philosopher).

Which included yet another footnote.

“As Littlejohn notes, caves on mountains provided those seeking to know the Dao with shelter for living, cooking and practicing inward stillness away from villages and towns. They were called earth lungs (difei), and later masters speak of them as filled with refined breath (jingqi) because they are places thought to concentrate the qi from which all things receive their power to live and take form.”

Difei is a word that had been baffling me while reading The Sword Heroines of the Shu Mountains. None of my dictionaries included it, but some major plot sequences revolved around events happening in a difei. I was delighted to find enlightenment via almost random obscurity. Suddenly, I felt the thrill of the hunt. Sure enough, as I continued to indulge my curiosity about medieval Daoism, Tang dynasty immortals, sacred Sichuanese mountains and Li Bai, I gradually began to comprehend just how much of the world-building in The Sword Heroes of the Shu Mountains was rooted in medieval Chinese culture, and specifically, in the Tang dynasty (618-907).

The glorious Tang!

Widely considered the peak of classical Chinese culture. Home to the greatest poets and painters in Chinese history. The highpoint of Daoism insofar as it was embraced by the state: the Tang imperial line even claimed direct descent from Laozi.

An age of wonder: As T. H. Barrett reports in Taoism under the Tang, during this period “a constant stream of miraculous happenings was reported to the throne from throughout the empire.”

An age of relative feminist autonomy: “The Tang dynasty has the reputation of being a good time for women,” writes Suzanne Cahill in Divine Traces of the Daoist Sisterhood. “Bound feet were still in the future. Women could inherit property and widows could remarry.” Emperor Wu, the only woman who ever ruled China under her own name, lived during the Tang. “The one religious tradition in China that assigned any value to the female sex was Taoism,” asserts Barrett.

An age of multicultural amity: The ruling family may have claimed Laozi as its ancestor but there’s better evidence for hereditary connections to Central Asian nomads who moved into the north China during the disarray following the end of the Han dynasty. The capital city of Changan wasn’t just the biggest city in the world during the Tang, it was also a melting pot of ethnicities and religions. “The Tang dynasty was one of the most cosmopolitan in Chinese history,” writes Charles Benn in China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. “Influences from abroad affected nearly every aspect of life, from music to medicine.”

If you are seeking escape from the current moment, what better destination than the Tang?

I saw my path forward reveal itself while I was in the shower one morning. I had to chuckle. I had spent countless hours in a Chinese fantasy novel without realizing it was opening up a secret tunnel through the grotto heavens that led to a fantasy-land that was real – the Tang! My intellectual wandering had merged with my commitment to escapism. This would be fun, I thought! I organized a research agenda.

I didn’t get very far before I had to pause and consider how the central paradox of the Tang fit into the big picture. Because the same man whose 40-year reign encompassed the peak of Tang glory, the Bright Emperor Xuanzong, was also the man who presided over and precipitated the definitive end of that age.

This is not the place to go into great detail about the waning years of the Bright Emperor’s reign, his love affair with the Precious Consort, Yang Guifei, and the great rebellion led by the Sogdian general An Lushan. It’s only the most told and retold story in the history of China. For my purposes, it’s enough to say that in the course of a single generation, the Tang Golden Age ended, with enormous consequences for the future direction of Chinese civilization. As Kidder Smith writes: “historians have argued that the Rebellion marks the biggest shift in Chinese history between the Qin unification of empire in 221 BCE and China’s transformation in the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries.”

And people experienced it in real time. Sometimes history happens fast. Li Bai lived through the Rebellion. So did Du Fu. Their before-and-after poems tell a traumatic story.

As far as imperial China is concerned, women would never again have it as good as they did in the Tang.

The era of cosmopolitan respect also withered away, perhaps due to lingering resentment against the “barbarian” insurgent An Lushan.

Kidder Smith again: “the Rebellion brought a racist backlash, and Marc Abramson argues that this “was perhaps the crucial point in the formation of an ethnically Han (as opposed to culturally Chinese) identity…. That is, the semi-permeable membrane of ‘Chineseness,’ which had been primarily constructed from an ability to manipulate the written texts of antiquity, hardened into a race-based criterion.”

I had been chasing transcendence, drunk on Li Bai’s poetry, dreaming of my own flying sword, imagining with delight a grueling pilgrimage up the slopes of Mount Emei. I was more than ready to spend my next few months in the company of elixir-concocting sages and banished immortals, when, plot twist, I suddenly saw my own moment in time reflected in the tragedy of the Bright Emperor.

As the summer of 2025 moves forward, and an overtly white supremacist project extends its control over every level of the government of the United States; as every civil rights victory of the last half century comes under sustained attack; as the infrastructure of science and rationality is itself relentlessly dismantled, it seems well within reason to imagine that future historians will point to Donald Trump’s second term as president as the moment the American democratic experiment failed. This shouldn’t really be a surprise. The distance between a civilization’s peak and its collapse can be as short as a single love affair gone wrong. These things happen.

Getting away from it all is, I guess, the whole point of climbing mountains and reading fantasy and seeking transcendence. But there’s no escaping, in these parts, the urge to make it all make sense or at the very least, figure out an effective coping strategy.

So to the Tang we go, to see what we can learn, but in the present we remain, preparing our poems of grief.

And as always, Li Bai is along for the ride.

Drinking alone at North Mountain, sent to Wei Six I never heard of ancient hermits buying a mountain to hide in. With Dao, all acts are pure, why worry if people are around? Now, as I descend this mountain ridge, all noise subsides, the earth’s at ease. A range of peaks unfolds across my doorway, a trickle cuts through rock, pulling down countless springs. The folding screen of cliffs is lost in clouds, their caverns unfathomably deep. At dawn and dusk the river shines its true colors, the woodland air draws tight with evening chill. That’s the moment to pick the Red Persimmon and cultivate the Mysterious Feminine. I sit with precious texts and the moon, brush the frost off my zither. In the darkness I pour wine and watch the shadows and empty the cup again. I miss you, out roaming the world’s dusty wind, why don’t you ever laugh at yourself? (Translated by Kidder Smith/Michael Zhai)

What a delight to stumble upon this today! (from whence I discovered other posts of yours and out-of-linear-time sequence commented upon, but I digress. Li Bai, a wuxia novel titled <Sword Heroes of the Shu Mountain>, Ge Hong, Shu kingdom, Li Bai again - I need travel no further in search of reading material today. Your bookshelf looks like mine, except I dont have <To die and not decay>. and i have now discovered that the Heroes of Shu Mountain is available, in English, as a web novel. Happy days!