While researching the mythology and lore of ginger, I made the unexpected acquaintance of the 17th century Dutch East Indies administrator Hendrik Adriian Van Rheede tot Draakenstein, and Itty Achudan, scion of a hereditary family of botanist physicians in the colonial state of Malabar. I found myself forced to set ginger aside, for the moment, and indulge in a peppery little saga of spice imperialism and 21st century transnational bio-piracy prevention...

The first rigorous botanical description of ginger in the Western historical record is contained in the Hortus Malabaricus, a gorgeously illustrated 12-volume compendium of the plant life of Malabar, a coastal region of west India that is now part of the modern state of Kerala. The Hortus Malabaricus (Latin for "Garden of Malabar”) was the brainchild of Hendrik Adriian Van Rheede tot Draakenstein, the governor of Dutch Malabar for seven years in the late 17th century.

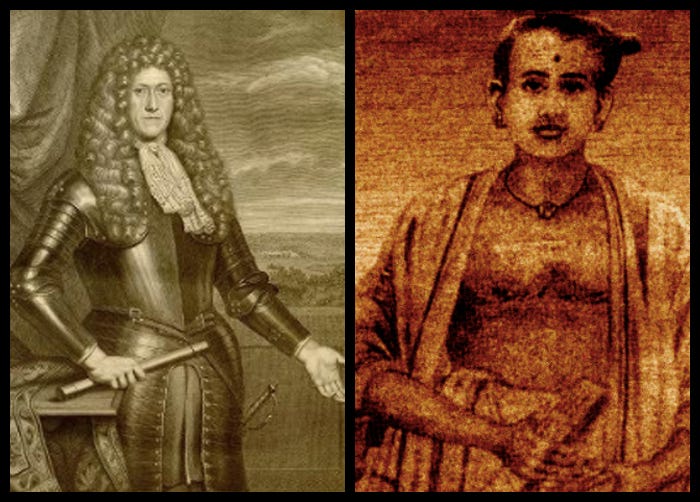

The descendent of influential Dutch nobility, Van Rheede was orphaned at age 4, left home at 14, became a soldier for the Dutch East India Company at 20, saved an Indian queen from the massacre of the royal family of Cochin at age 27, and all the while, maintained an intense interest in the flora of Western India.

(A sample illustration from the Hortus Malabaricus)

Praised by none other than the "father of modern taxonomy," the great Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, for the accuracy of its data, the Hortus Malabaricus is a monumental achievement. But while it is not all that surprising that a colonial administrator would be interested in local plant life -- the Dutch ousted the Portuguese from Western India precisely because they wanted control of the local spice trade (namely Malabar pepper) -- what really jumps out from a study of the origins of the Hortus Malabaricus is its hybrid identity as the product of a massive collaboration between the colonizers and the colonized in which everyone involved appears to have been motivated by the deepest principles of scrupulous accuracy and attention to quality.

According to a fascinating article written by the "doyen of Indian botany," H.Y. Mohan Ram, marking the publication of an English translation of the Hortus Malabaricus in 2003, the "stupendous undertaking" was the result of about 30 years of compiling and editing by a team of the best among 17th century European physicians, professors of medicine and botany, amateur botanists... Indian scholars and vaidyas (physicians) of Malabar and adjacent regions, and technicians, illustrators and engravers, together with the collaboration of company officials, clergymen" and local potentates including the King of Cochin and the ruling Zamorin of Calicut.

The most important of these collaborators was Itty Achudan, a member of the untouchable Ezhava caste and heir to a hereditary line of physicians that maintained a "family book consisting of several volumes of palm leaf manuscripts... in which were recorded names of medicinal plants, methods of preparation and application of drugs and the illnesses for which they were used." The information in these palm leaf manuscripts, a priceless repository of hundreds of years of family traditions, was the primary source for much of the botanical information on the properties of Malabar flora.

"The courage shown by Van Rheede, the powerful ruling Dutch Governor," writes Ram, "by inviting Itty Achudan to collaborate with him as an equal in the compilation of Hortus Malabaricus, respecting his knowledge and competence and ignoring his social status, should be considered as an important milestone in the social history of Hindu medieval Malabar."

Sadly, the institutional realities of European imperialism's impact on our global collective discourse mean that we know considerably more about the life of Van Rheede than we do about Itty Achudan (although his name does live on as a genus classification in the Urticaceae family). But Ram offers a provocative footnote. In his appraisal of the twentieth century Keralan botanist K.S. Manilal's 35-year-long effort to translate the Hortus Malabaricus both into English and the indigenous Kerala-region language Malayalam, as well as update its botanical information with state-of-the-art clarity, Ram underscores a subversive irony.

Paradoxically Hortus Malabaricus, originally meant to provide foreign powers a resource base in India, will be helpful through its English edition in safeguarding hundreds of Indian medicinal plants to prevent patenting against Indian interests and will act as a weapon against the negative impacts of globalization.

This is no idle concern. A number of Indian botanical products, including the neem tree, tamarind, and turmeric have already been patented by foreign firms, a latter-day hobby of transnational corporate capitalism known as biopiracy. It is a neat twist of fate that the translation of hundreds of years of the Achudan family's accumulated store of medico-botanical wisdom into English, the language of India's most disastrous colonizer, could be considered a line of intellectual property defense against further such incursions.

(Ginger!)