How to Cook and Eat and Reform Chinese

Cool Footnote: the Thanksgiving-scallion-pancake-Leibniz edition

In preparation for the next installment of my series on Leibniz, Jesuit missionaries, the Chinese language, the Book of Changes and the Chinese computer I have been reading a pair of recently published books investigating the great drama of “Chinese script reform.” Both Codes of Modernity: Chinese Scripts in the Global Information Age by Uluğ Kuzuoğlu, and Chinese Grammatology: Script Revolution and Literary Modernity, 1916–1958, by Yurou Zhong, are deep and fascinating investigations of a great Chinese cultural drama: the conclusion of Chinese intellectuals that Chinese characters had to be either massively simplified or dumped entirely if China was going to successfully modernize.

More on that later. But for now, let us contemplate the fact that both books prominently feature the Chinese linguist Yuan Ren Chao, who, in 1916, at the age of 24, published an enormously influential essay titled The Problem of the Chinese Language.

As I was reading about him this morning, I couldn’t shake a nagging feeling that I knew his name from a context completely separate from script reform. A context, I suddenly realized, that held the power to finally link my current Leibnizian rabbit hole to the ostensible binding force that is supposed to hold this newsletter together: my kitchen!

Because, as I quickly ascertained after riffling through my cookbooks, Yuan Ren Chao was indeed the husband of Buwei Yang Chao, the author of How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (named, just a week ago, one of the 25 best cookbooks of the last 100 years by the New York Times.)

Buwei Yang Chao will forever be remembered for coining the terms “stir-fry” and “potsticker,” but she was also a doctor in her own right and a pioneering advocate of birth control. I am avidly looking forward to the 2026 publication of The Formidable Mrs. Chao by Jen Lin-Liu for more information on this amazing woman.

But for now, I think back to a gathering in Washington D.C. some years ago, in which I was getting acquainted with my now good friend Howard Spendelow, a professor of Chinese history. Learning of my interest in Chinese cuisine, he pulled out his tattered copy of How To Cook and Eat in Chinese and directed me to read aloud the recipe for “Stirred Eggs.”

It starts with a note from the author:

Learning to stir-fry eggs is the ABC of cooking. As this is only dish my husband cooks well, and he says that he either cooks a thing well or not at all, I shall let him tell how it is done:

What follows is a set of absurdly detailed instructions that sounds something like a computer program with a dead-pan sense of humor. I will include just one excerpt:

Either shell or unshell the [six] eggs by knocking one against another in any order.

This instruction comes with its own footnote!

Since, when two eggs collide, only one of them will break, it will be necessary to use a seventh egg with which to break the sixth. If, as it may very well happen, the seventh egg breaks first instead of the sixth, an expedient will be simply to use the seventh one and put away the sixth. An alternate procedure is to delay your numbering system and define that egg as the sixth egg which breaks after the fifth egg.

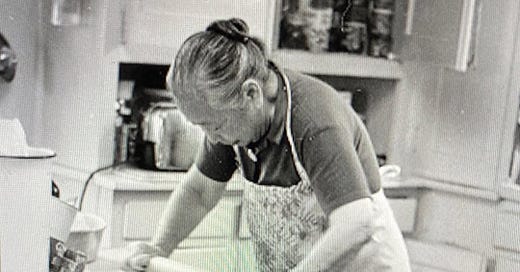

Now for my own footnote to complete this festival of cool footnotes: Yuan Ren Chao and Buwei Yang Chao lived for many years in my hometown of Berkeley, California. Almost exactly a year ago the author of the forthcoming biography of Buwei, Jen Lin-Liu, posted a picture of her working on some dough on a chopping block in her Berkeley home. (See above!) Lin-Liu speculated that she was “rolling out what might be Chinese dumpling wrappers or scallion pancakes or maybe a Thanksgiving pie.”

I’m just going to declare, without any evidence, that we are witnessing incipient scallion pancake creation. This is purely self-serving, because I make scallion pancakes for friends and family almost every Thanksgiving weekend, and I will in fact be doing so about 48 hours from now.

And as I do so I will toast the memories of my long-departed Berkeley neighbors, Yuan Ren and Buwei Yang Chao, a dynamic couple who were simultaneously reformers, modernizers, and conduits of Chinese culture.

And I will likely also pour out a glass for Gottfried Leibniz, undoubtedly one of the most profound philosophers of infinite interconnection who ever lived. Because the journey from his quest for a universal language in the 17th century to scallion pancake solidarity, Berkeley-style, in the 21st, is simultaneous completely unexpected and yet, somehow, inevitable.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone.

That’s Mila, Max and Davina’s daughter!

Is that Alison?

Fun to read