Death knell for dynasties: "The people are eating insipid food."

Diced chicken and the Dowager Empress: Part II of the Chronicles of Salt and Sichuan

What can you taste from a bite of gongbao jiding? There's the obvious: the crunch of peanuts, the bite of chili peppers, the numbing ma of whole Sichuan peppercorns, the tenderness of the quickly stir-fried chicken. Then there is the more subtle: the sauce that combines sugar, soy sauce and black vinegar into sweet and savory perfection.

Gongbao jiding (aka Kong Pao chicken) is a ubiquitous standard bearer of Sichuan cuisine for obvious tasty reasons. But there is a wider universe accessible beyond the taste buds, a world with characters -- corrupt eunuchs, brilliant salt miners, Daoist hydrological engineers, and upright Confucian officials -- and historical flow.

Part II of the Chronicles of Salt and Sichuan (Part I is here):

By the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the easy pickings for salt production in Sichuan, all those brine springs and shallow wells, had been mostly exhausted. In the 11th century, salt miners in the town of Jingyan, 130 kilometers south of Chengdu, devised ways to drill holes hundreds of meters deeper than ever before by deploying cables constructed from linked pieces of bamboo and an assortment of wonderfully sophisticated iron drill-bits. Access to previously unreachable sources of salt exploded. By 1132, Sichuanese officials recorded nearly 5000 brine wells in the province.

From a history of technology perspective the achievement is noteworthy because the record shows that Sichuanese deep drilling accomplishments predated similar European technological capacity by hundreds of years. But the breakthrough was also significant, argues the Chinese economist Liang Pinghan, because it led to a huge increase in Sichuan's per capita production of salt, which in turn influenced changes in Sichuanese cuisine.

Prior to the Song Dynasty, Sichuanese dishes tended to be sweet, a consequence, Liang suggests, of Sichuan's importance as a center of sugarcane cultivation. But the falling price of salt changed the menu. Sweet was out. Salty was in. There is a direct connection, asserts Liang, between Sichuan's marvelous abundance of paocai -- pickled vegetables -- and its ready availability of salt.

The Taiping Rebellion in the middle of the 19th century precipitated another step forward in the evolution of Sichuanese cuisine. The cataclysmic uprising cut off central China from its traditional southeastern sources of salt. Sichuan filled the gap, and as demand overtook supply, the price of salt shot up. Sichuanese cooks, argues Liang, responded to the price signal by substituting in the chili peppers which immigrants from Hunan had been bringing with them for the last century or so.

Liang's deterministic thesis of culinary innovation raises questions that are fun to grapple with. How much of the "culture" of a particular region is defined by contingent factors like Triassic-era brine deposits, bamboo-chain drilling innovations, and fluctuating commodity prices, as opposed to the free will and intellectual creativity of human beings? Do people develop a cuisine from the wellsprings of their own inspiration, or are culinary choices imposed upon them by their historical and geographical context?

The binary approach is of course too simple. Like a classic Sichuan dish, the likeliest answer is a stir-fry of multiple overlapping taste sensations.

Consider, for example, gongbao jiding.

According to the lore-masters of Sichuan, gongbao jiding is associated with Ding Baozhen, a Qing dynasty official who served as governor of Sichuan in the late 1800s and enjoyed a reputation as a discerning gourmet. The term "gongbao" is an abbreviation for an honorary title, taizi taibao -- usually translated as "Grand Guardian to the Heir Apparent" -- that was posthumously awarded to Ding for his services to the throne.

The most detailed account of the invention of gongbao jiding that I have unearthed so far dates the provenance of the dish back to Ding's previous tenure as the governor of the northeastern province of Shandong. It is said that one day, while taking an incognito walk around Shandong's capital, Jinan, Ding followed his nose to a restaurant in pursuit of an unfamiliar but alluring aroma. The cook invited Ding to sample his signature dish, a sweet and savory mix of diced chicken and peanuts. Ding loved it so much he hired the cook for his personal household. After Ding was transferred to Sichuan, the cook followed. Not long after their arrival, Ding hosted an important dinner. He requested that the cook prepare his favorite dish. But the difference in available ingredients (more than a thousand miles separate Chengdu from Jinan) forced the cook to scramble. In came the chilis and Sichuan peppercorns.

Here we have both personal agency -- gourmet official, top chef -- and contingent circumstances -- regional variation in ingredients -- playing a role in the creative act. This rings true for any cook making things up after a glance inside the refrigerator. But even so, this story has always seemed a little too pat. Gongbao jiding consists of exactly the kind of cheaply available ingredients, stir-fried quickly together, that is the epitome of Sichuanese peasant home cooking. It has none of the markings of elite top chef craftsmanship that one would expect from the personal cook of a high-ranking Qing official. So I'm suspicious. The association with Ding positively reeks of elitist appropriation.

In "The Origin Story of the Late Qing Official Ding Baozhen and Gongbao Jiding," published in the Chinese journal Poultry Science in 2014, author Kang Peng recounts many of the exploits that won Ding his honorary gongbao title. According to Kang, Ding is most remembered for two primary accomplishments: gongbao jiding, and the execution of An Dehai, the favorite eunuch of the Dowager Empress Cixi.

And that's where the plot starts to thicken.

The picture shown above is a screen shot captured from the 1989 Chinese-language movie, The Dowager Empress. The film is notable for a number of reasons. It was directed by Li Han-hsiang, an influential contributor to the film industries of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China who made a hobby of bringing to celluloid life a parade of stories about notorious women in Chinese history, including Xi Shi, the legendary fifth century B.C. beauty deployed as a pawn in Warring States-era machinations, and Wu Zetian, the Tang Dynasty empress who was the only woman to rule China under her own name. The 1989 Dowager Empress film was actually Li's second movie portraying Cixi, the 'behind-the-curtain" ruler often blamed for sabotaging any chance for the Qing Dynasty's long term survival.

Cixi is played by Liu Xiaoqi, a Sichuanese native and former Mao-idealizing Red Guard (seriously: in her memoir, I Did It My Way, she delivers the memorable line: "Chairman Mao: You were my first object of desire.") Liu portrayed Cixi in no fewer than four separate movies. She was also possibly China's most famous female movie star at her peak before being eclipsed by her Dowager Empress co-star, Gong Li. In one of her very first roles, Gong Li plays a hapless maid-servant to the equally hapless Tongzhi emperor, but is sold off to a brothel halfway through the film by the eunuch An Dehai.

An Dehai has a significant role in The Dowager Empress. He is depicted as a major force in the Forbidden City, browbeating historically famous Qing officials, micromanaging the Tongzhi emperor's love life, and helping Cixi scheme against her co-Dowager Empress, the late emperor's wife Cian. And judging by Cixi's moans in reaction to his ministrations, he was also a quite accomplished massage therapist.

For reasons not entirely clear in either the movie or the historical record, An Dehai eventually seeks Cixi's permission to set out on a triumphal tour of some of China's other metropolises, purportedly to purchase special provisions for the Empress. According to imperial law, court eunuchs were not allowed to leave the capital, but Cixi's affection for An is so great that she grants him leave.

Sadly, the movie avoids explicit visuals of An Dehai's road trip. This is a shame because surviving accounts suggest he did not behave himself with decorum. The author Princess Der Ling, who served as a lady-in-waiting in the imperial court, tells us in her utterly unreliable biography of Cixi, Old Buddha, that his residence in one city "became the house of orgies such as no pen may describe, by which no book may be sullied in the printing."

Eventually, An Dehai made his way to Jinan, the capital of Shandong. But there, alerted by An's enemies in Beijing, our gongbao jiding hero Ding Baozhen was waiting. Citing the imperial proscription against eunuchs leaving Beijing, Ding detained An. He promptly informed the court of the arrest, but then proceeded to execute the unfortunate eunuch before Cixi's order for his release arrived a few days later.

Eunuchs and women always get blamed when Chinese dynasties go awry, and both The Dowager Empress and Old Buddha are excellent examples of latter day pop cultural representations that take their cues from such bias. (I found this film catalogued at one library under the English-language title "Evil Queen.") Cixi is rarely portrayed as a sympathetic character. On the contrary, she is generally blamed for crushing China's attempts to reform itself, for provoking the disastrous Boxer Rebellion, and for murdering multiple members of her own family. The phrase "this is the end of the Qing dynasty" is repeated twice during the film by officials aghast at all the disreputable Forbidden City goings on.

The An Dehai incidence is one of the the building blocks for Ding Baozhen's enduring reputation as an upright Confucian official unafraid to challenge corruption or tyranny. But one thing started to puzzle me as I chased down the details. The traditional historical explanation of Ding Baozhen's decision to execute An Dehai is that it was part of a power play masterminded by Cian, the other Dowager Empress. But if so, how did Ding survive the aftermath? Cixi eventually triumphed over all her rivals. If she was so evil, and if An Dehai was truly so cherished, why didn't she take revenge on Ding Baozhen once she seized power? She certainly had plenty of time. An Dehai's execution occurred in 1869. Cixi fully consolidated her control in 1875. Ding Baozhen served as a high-ranking official until 1886.

For a perfect example of Cixi's bad press, let's return to Old Buddha. Princess Der Ling declares that Cixi did take revenge on Ding. She writes that Cixi "transferred him to the most difficult, the most thankless post in all China, a post which none might manage."

"In such a place it is not surprising that he failed to acquit himself with honor.... In a short time after his new and disgraceful appointment, he was haled before the court to answer charges of negligence, fraud, and scores of others, to which no answer he could make served to satisfy the Empress Dowager. In the end, he was banished forever from court -- his banishment to affect his descendants to the end of time -- which meant he might never again hold office, that his children might never take the examinations for official positions, in short that the erstwhile governor and his descendants were doomed henceforth to live on a par with humble coolies."

Even if we accept the possibility that Sichuan was "the most thankless post in all China," the rest of this passage is fake news. Ding died in office as governor of Sichuan, was posthumously honored by the throne, and as far as the historical record is concerned acquitted himself with considerable success at every stage of his career -- during an era in which imperial China was assailed on every front. After his death, special temples were erected to celebrate his memory in Shandong, Sichuan, and Guizhou (the province of his birth.) As Kang Peng summarizes,

"During Ding Baozhen's terms of office as governor of Shandong and Sichuan, he confronted domestic trouble and foreign invasion, national decline, political corruption, and repeated outbreaks of social chaos. From the beginning to the end he made it his duty to save the country and the people by building irrigation works, killing bandits and rebels, reorganizing political administration, instituting a process of Westernization, and being solicitous of the hard-pressed citizenry. During this period he enjoyed a national reputation as one of the Qing officials with the greatest record of achievement."

"Especially notable," adds his biography in Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, was "his reform of the salt administration [in Sichuan.]"

Kang provides an excellently lurid explanation for Cixi's reluctance to crush Ding. Apparently, there was a rumor among the common people that An Dehai was a false eunuch, that he was not, in fact, castrated, and that he had been having sexual relations with the Dowager Empress. But after the execution, Ding Baozhen ordered that An Dehai's body be exposed to the general public for three days, which gave ample opportunity to anyone interested to inspect the body and conclude that, yes, he was indeed a eunuch. A grateful Cixi, so the theory goes, declined to punish Ding for this service to her reputation.

Cool story. But could there be a simpler answer? Maybe Cixi was not quite the completely un-remediable disaster that her critics allege? What if she declined to seek revenge because she recognized that Ding Baozhen was a rare and valuable commodity in the waning days of the Qing: an energetic and competent official who dedicated himself to doing everything he could to keep the empire afloat?

A man whose hard work was remembered so fondly in Sichuan that his legacy ended up including responsibility for one of the region's most popular dishes?

"Especially notable was his reform of the salt administration..."

In 1896, George Litton, a British consular officer stationed in Sichuan and Yunnan at the end of the 19th century, wrote a column for a publication called The Engineer describing "one of the oldest engineering undertakings still in regular service anywhere in the world."

For two thousand years, the Dujiangyan waterworks had both watered the Chengdu plain and provided flood protection. According to Litton, the keys to its success were the design principles set down by its original architect, Li Bing: "dig the channels deep and make the dikes low."

In other words: "keep the water at its natural level." This is advice that seems at once obvious and yet has often been ignored throughout the ages by Chinese hydraulic engineers. Chinese history is littered with catastrophic floods that resulting from the collapse of dikes towering over the surrounding landscape, particularly in the north central plains traversed by the Yellow River -- "China's sorrow."

As if to underscore his point, Litton closes his account with a paragraph taking a swipe at the Qing dynasty official who governed Sichuan from 1876-1886.

"The Viceroy, Ding Baozhen... got into trouble by making the big dike too high when he repaired it, with the result that too much water came through the gorge, and the plain was flooded."

Ding Baozhen!

I had already made Ding's acquaintance long before I read this sentence. Every Sichuanese cookbook worthy of the name notes his association with gongbao jiding, and the most cursory review of his biography makes it clear that his reorganization of the salt industry in Sichuan was a major accomplishment. Given the importance of salt to Sichuan's history and economy, and my own love for gongbao jiding, these two factors were sufficient to ensure that Ding would be a key player in my Sichuan obsession.

But his connection to the Dujiangyan irrigation systems was an unexpected revelation; it delivered a rare moment of epiphany; the swirling kaleidoscope of random facts that I am always collecting suddenly resolved into a potent geometry of meaning.

If there is a deep structure to Sichuan civilization, Dujiangyan -- the irrigation infrastructure that made "the land of plenty" possible -- is a core part of it.

The great historian of Chinese science and technology Joseph Needham declared that the Dujiangyan irrigation and flood control waterworks, the oldest continually operating hydraulic engineering system in the world, "can be compared only with the ancient works of the Nile." Li Bing, the original architect, derived such fame from it that he was eventually worshipped as a god. The state of Qin leveraged the newly irrigated Chengdu plain as logistical support for its conquest of the rest of China. The immigrants who repeatedly flocked to Sichuan's safe haven over the centuries were drawn by the relative prosperity promised by Dujiangyan. There is even a theory that the fun-loving, food-obsessed, hang-out-in-the-tea-shop-all-day-gossiping qualities that are often said to characterize the residents of Sichuan can be traced to Dujiangyan. Peasants had it so easy on the Chengdu plain that they had ample leisure time to eat and drink!

In Sichuan, following the flow always leads one back to Dujiangyan. Li Bing's hydro-engineering project has fascinated generations of engineers and environmentalists because, according to one line of argument, it embodies a theory of design that optimizes for resilience and sustainability. Dujiangyan is said to exemplify a Daoist school of hydraulic engineering that emphasizes working in concert with the essential nature of water: One must figure out where the water wants to go, and design accordingly. The Confucian school of hydro-engineering, on the other hand, is said to concentrate on controlling and dominating water, and therefore results in structures that are brittle and prone to catastrophic failure.

Is there a blueprint for environmentally-sustainable infrastructure that supports and protects the livelihoods of millions of people for thousands of years to be found in Dujiangyan? Since I started exploring my own attraction to Sichuan food five years ago, answering this question has unexpectedly become one of my key research priorities. So I was delighted to see Ding's name connected to Dujiangyan, even in a negative context. Talk about your pure literary serendipity! I could start with a bite of diced chicken and end at the center of the Sichuan universe. That's my kind of flow.

Did Ding really fail to observe Li Bing's maxim and accidently flood the Chengdu plain? It seems like an important point to nail down but so far, I have yet to find any primary source confirmation of Litton's allegation. The material I've reviewed only mentions how in both Shandong and Sichuan, he made flood protection and irrigation a key priority, which is exactly the kind of thing one would expect from a conscientious Confucian official.

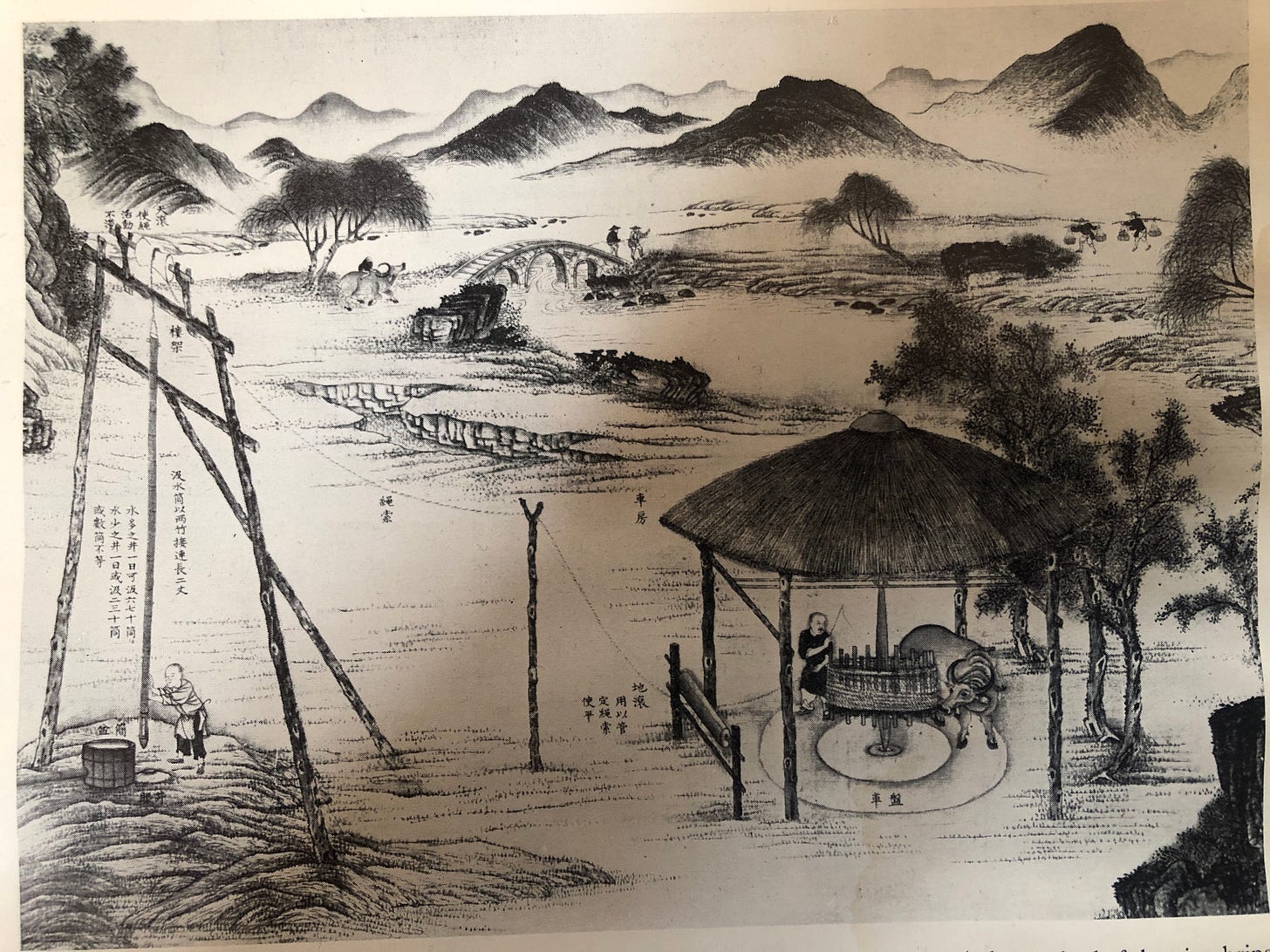

What we do know is that his comprehensive reform of Sichuan's salt administration was a huge success. And this was no trifling matter. By the late 1900s, the Sichuan salt industry employed over a million workers. Ziliujing, the pulsing heart of the salt well district, featured a fantastic landscape of interweaving bamboo tubes that funneled both brine and the natural gas that was burned to evaporate the brine. (The Sichuanese may well have been the first people in the world to find a commercial use for natural gas, which they discovered emanating from the same holes they dug to obtain brine.)

But in the 1870s, Sichuan's salt industry was wracked with graft and hobbled with crippling transport taxes. Within a year of arriving in Sichuan, Ding addressed the structural problems hobbling salt reform with a set of reforms. In Salt and Civilization,Samuel Adshead reportsthat the surge of revenue generated by these reforms was critical to the survival of the Qing dynasty.

"Thus Sichuan salt contributed to the suppression of rebellion, accommodation with the foreigner and the beginnings of modernization. In particular... it contributed to two of the most notable Chinese enterprises of the nineteenth century: Zuo Zongtang's re-stabilization of the Inner Asian frontier and Li Hongzhang's stabilization of the maritime frontier."

The largesse of Sichuan, coming to the imperial rescue again! In the second century B.C. the logistical abundance of Sichuan, which included both salt and the grain irrigated by Dujiangyan, contributed to the creation of imperial China. Two thousand years later, Sichuanese salt helped to prolong the last days of China's last imperial dynasty for a few decades longer.

Getting the salt market straightened out was one of the most important things a province's governor could undertake. In China, the phrase "'the people are eating insipid food'," writes Adhead, "was a recognized symptom of social breakdown and a danger signal for an upsurge of banditry. Chinese history was full of rebels who started as salt smugglers."

As we learned in Part I, Sichuan's "culture heroes" often became associated with salt production. With Ding, it may have worked the other way around. His success with the salt industry made him a culture hero. As the decades passed, and Sichuan descended into revolution and warlord chaos, the memory of one of the province's last truly effective governors became associated with a dish that is the very antithesis of insipid -- gongbao jiding.